Time banking: bank holidays, the four-day week and the politics of time

Time banking: bank holidays, the four week and the politics of timeArticle

Over the weekend, Labour announced that it will create four new bank holidays, one on each of the UK’s patron saint’s days, if it forms the next government.

The intention behind the pledge was two-fold: to help bring together the four nations of the UK around special national days, while ensuring that the economy remunerates people in time, as well as pay.

It also hints at a longer term goal, using public policy to transition the UK towards a lower work, higher productivity future, out of its current low productivity, long-hours model.

The UK currently has only eight public holidays a year – the fewest of any G20 or EU country. Moreover, we work longer hours than many other major advanced economies. In 2015, the average annual hours per worker in the UK was 1,674, compared to 1,482 in France and only 1,371 in Germany.

Yet though we work longer, we don’t work better. As economist Chris Dillow has written, across the 35 OECD nations, there is a strong negative correlation between annual working hours and GDP per hour worked. This isn’t evidence that either one causes the other. But it tells us that those economies with lower hours than the UK are, almost without exception, also able to compensate with higher productivity.

This is not simply of academic interest. It also has serious implications for British workers, since it is higher productivity that is the enabler of higher pay. And right now the UK has a crisis in earnings, ranking 103rd out of 112 countries – and second worse in the OECD only after Greece – in terms of real wage growth between 2008 and 2015.

In other words, we have an economic model where on average we work longer, less productively, and for worse real wage growth than most other advanced economies.

It’s intriguing, then, that much of the media reaction to these proposals appears disconnected from this broader economic debate.

Indeed, some high profile commentators appear not even to fully understand some of the key concepts. For example, in his interview with Jeremy Corbyn over the weekend, Andrew Marr, apparently confused productivity with output: reporting that productivity could fall by between £1 and £2 billion pounds as a result of the new holidays.

Factually this is nonsense. Productivity is a measure of how much output we get for the time we put in, measured in the tens of pounds, not billions. Furthermore, the direct numerical effect of reducing the amount of time spent working can at worst have only a neutral effect on productivity – in fact, as we have seen, it is more likely to coincide with an improvement.

On the one hand, a loss of output due to a loss of hours worked is a legitimate concern. But there are also reasons to believe that, up to a certain number of bank holidays, this effect would be offset by productivity gains elsewhere. This could partly be due to Parkinson’s law, whereby the time a task takes to complete tends to equal the time available. Assuming this is true, more holiday would see an adjustment to achieving the same output in less time. The fact that people will have more time to spend money, and firms will need to find ways of increasing output to meet demand while hours are constrained hours, may also help. There is also evidence that tired and jaded workers are, unsurprisingly, likely to be less effective.

This also raises bigger questions around time and work. As automated processes are increasingly substituted for labour, and the rise of ‘digital Taylorism’ intensifies over the coming decades, working time is likely to become an increasingly important site of political struggle and policy debate.

Bank holidays represent one possible way of ensuring workers are remunerated in both time and pay. But this is also expensive for firms who are obliged to pay the same salary for fewer hours worked - beyond a certain number of bank holidays, the economic positives may no longer outweigh the negatives.

One alternative would be to reduce the working week. IPPR analysis has shown that even moving to a four-day week may not be a fiscal impossibility.

Modelling conducted as part of our analysis of the 2020s has shown that if all full-time contracts were reduced in hours by 20 per cent (or to 30 hours, whichever is lower), and part time contracts were topped up by six hours (or raised to 30 hours, whichever is lower) then around 16 per cent of hours would be lost from the labour market – with the corresponding loss in pay and tax receipts.

However, if this were accompanied by a rise in the minimum wage by a round a fifth (relative to what it would otherwise be by 2030), the effect on government finances would be broadly neutral, if not slightly positive This is despite an aging population increasing the costs of pensions and reducing the proportion of people in work and paying taxes. However it also assumes that there would be no effect on employment. In reality this is highly uncertain, but in theory the effect on employment could go in either direction. A higher minimum wage could make employers less likely to take on new staff, but reducing the number of hours worked by a given person may mean that more people need to be employed.

Unlike increasing the number of bank holidays, such a move would focus employer efforts at increasing productivity, particularly in lower paid jobs, precisely where the highest gains are likely to be found.

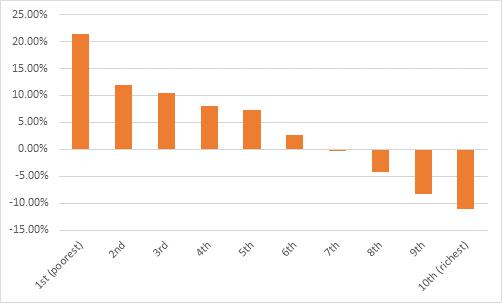

It would also significantly reduce inequality. The poorest 50 per cent of households would have incomes that were between 7 and 21 per cent higher than they would otherwise be, while incomes for the richest 10 per cent would be 11 per cent lower.

Average change in disposable household income, by equivalised household income decile (per cent, 2030)

Source: IPPR tax benefit model using data from the Family Resources Survey (2014/15), and uprated using ONS (various datasets) and the OBR’s Economic and Fiscal Outlook (various years).

Note: Figures denote the effects of a four-day week and enhanced minimum wage in 2030/31, compared with a ‘no-change’ baseline scenario also uprated to 2030/31. Both scenarios take account of an aging population. The IPPR tax-benefit model is a micro-founded model that estimates the impact of policy reforms prior to any behavioural effects

Working time has always been central to progressive economic campaigns, from the fight for the weekend in the 19th century to campaigns for an eight hour working day in the 20th. As technology reshapes how we live and work, and our social, economic and political institutions in the process, the question of how we distribute time and leisure is likely to grow in importance. Labour’s proposal is likely to be only the opening salvo in this debate. But as a country we desperately need a deeper conversation about how and when we work – and the institutions shaping work, leisure, and ownership - to address the fundamental and longstanding weaknesses of the UK’s economic model. This is precisely what the IPPR Commission on Economic Justice intends to do.

Related items

Change you can board: Delivering better, greener buses

The bus services bill is an opportunity to ensure reform really means thriving, green 21st century local bus networks in England.

Harry Quilter-Pinner on BBC Radio 4 Today discussing political donations

Modernising elections: How to get voters back

Elections are the defining feature of modern democracy. They are the process by which we express a desired future en masse. It is the mass dimension that matters most; it is the mass dimension that is receding.