Breaking the cycle: Essential pillars for an effective child poverty strategy

Article

The government has committed to a child poverty strategy, complete with a task force, due to report in the spring.

Following over a decade of languishing living standards and growing food bank use this is very welcome news at a critical time for the country. But what does this actually mean and what should it encompass? At its heart any strategy must be geared around children living better lives and having more opportunities than they do today – but there are wide ranging views on how to achieve this. This blog examines our thinking on the dimensions of the problem and what policy areas could be in scope to address these challenges.

First and foremost, the government must look at tackling low household incomes – both through bolstering social security and through policies to support more and better paid work for those who can. However, it’s also about supporting the families with the costs people face – whether that be housing, childcare, or household bills, which reduce the income available for everything else. Finally, it should comprise action on mitigating poverty – that is, policies which do not directly improve household material circumstances (by increasing income or reducing costs) but that reduce direct harms arising from being in poverty, both direct and indirect.

At its heart any strategy must be geared around children living better lives and having more opportunities than they do today

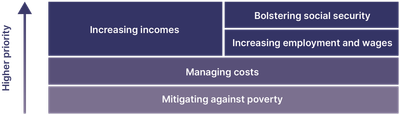

In our view, bolstering social security should come top of the priority list, followed by increasing employment and wages. Next should come managing costs with mitigating the effects of poverty after that.

Figure 1: Approaches to tackling child poverty

How did we arrive on this prioritisation?

- Increasing incomes is generally preferable to managing costs, given people are usually best placed to know where to spend limited money based on their individual circumstances and needs. In particular, social security options can provide immediate support for struggling families, whereas increasing employment and wages will inevitably take longer.

- Policies which reduce costs are second-best in they may pre-suppose what people need and could lead in some cases to the government spending money on things that people in poverty would not choose if they had the option.

- Finally, mitigation is the lower priority given the aims of any child poverty strategy must be to tangibly reduce child poverty. Put another way, policymakers cannot resign themselves just to treat the ‘symptoms’ of low income rather than dealing with the underlying causes of poverty. That said, action in this space could still be hugely valuable in improving lives today and in the future and should remain core to any strategy.

Strengthening social security must be a central plank to any child poverty strategy

Any government serious about tackling poverty will need to look closely at the social security system it has inherited.

Both the two-child limit and benefit cap arbitrarily limit benefit entitlement below the minimum amounts designed by the system – disproportionately harming large and lone parent families who face some of the highest rates of relative poverty. But beyond that, it should acknowledge that core levels of social security are incommensurate with need and must be better aligned to the costs people face and may face in future. In many situations, either on a temporary or permanent basis, and through no fault of their own, full-time work is not a viable option for some parents – and the current system acknowledges this is in very limited ways.

They should also consider design aspects of universal credit (UC), for example by looking at alternatives to the five-week wait at the start of a claim which leaves families without support or saddled with debt. It should examine how best to recover payments and reconsider whether the constant threat of sanctions is conducive to effective job search. A social security system which makes life very hard for its recipients will never support people into good work, either because the stresses of the system actively hinder work search, or they push people into poor quality work which may be unsustainable, fuelling a ‘low pay, no pay’ cycle. It means people do not reach their full potential, harming productivity and economic growth as well.

A social security system which makes life very hard for its recipients will never support people into good work

Boosting incomes through employment is a cross-government endeavour

The second way to boost incomes is through boosting employment and earnings. The Department for Work and Pensions must provide meaningful employment support, going beyond a ‘tick-box exercise’ and towards genuine engagement with people’s barriers to work. It should consider options for working much more closely with local partners and offer support which makes sense for places and the local economic context in which people find themselves. It must offer a service people want to engage with.

Importantly, the government must not just focus on getting people into work but, given increasing rates of in-work poverty in recent years, must also consider seriously how it can support and empower people on low wages to improve their earnings.

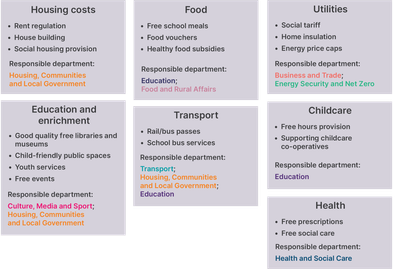

But any government seeking to support employment and wages should go beyond what happens at the jobcentre, given the myriad reasons why parents can struggle in the labour market. Figure 2 maps out common employment barriers against potential policy levers and where they would sit in government. Whilst not intended to be exhaustive, it demonstrates the breadth of policy challenges which hide under the bonnet of boosting employment: from childcare provision, to enforcing ‘blind’ recruitment practices to rural bus services. Notably these policy remits go far beyond traditional ‘social policy’ departments. In particular, the Department for Business and Trade should have a key role, given its potential role in shaping employer behaviour through incentives and setting 'the rules of the game' through employment law.

Figure 2: Tackling different barriers to employment across government, illustrative examples

Managing costs is also key to reducing poverty

There are a number of costs associated with running a household and raising children which could be reduced or eliminated for low-income households. We map these out below against likely responsible government departments, again to be illustrative of the wide scope rather than being exhaustive.

Figure 3: Potential ways of reducing costs for families

Policies to mitigate poverty should also be part of a child poverty strategy

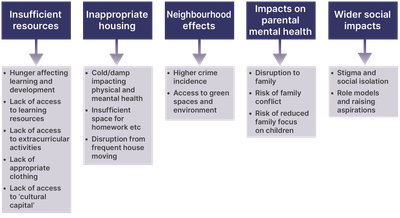

Finally, there is mitigation. To consider opportunities to reduce harm requires us to map out the transmission mechanisms by which children growing up in low-income can negatively impact their health, education and future employment outcomes.

The core areas we consider are the following.

- Insufficient parental resources, leading for example to hunger and children missing out on experiences affordable to their higher income peers, such as school trips.

- Poverty placing a persistent strain on parents leading to poor parental mental health – which can then affect children directly and indirectly.

- Poverty forcing parents to live in housing which can be inappropriate for their family needs.

- Living in neighbourhoods with increased risk of exposure to crime, less access to good schools, community activities or safe green space, for example.

- Wider social impacts such as stigma and lack of access to role models.

Figure 4: A preliminary mapping of how growing up in poverty can affect other child outcomes

This mapping opens up a range of potential policy levers, some shorter-term and others longer-term, to improve children’s outcomes, sitting across a range of government departments as well as devolved administrations.

How to make these choices

This blog highlights a wide range of policies which could potentially form part of a child poverty strategy and there will clearly be a need to prioritise – whether that’s addressing barriers to employment, reducing costs or directly mitigating the effects of poverty. We consider some of the key dimensions for a government to consider in making this prioritisation.

- Prioritisation by experts by experience: Listening to people with lived experience of life on low incomes to inform prioritisation of what would make a difference.

- Stigma: How far policies can lead to stigma, noting the way that how government both talks about and implements policies can affect this.

- Respecting autonomy: The extent to which policies give people choice or agency – or the opposite.

- Implementability: The extent to which the policy can be effectively targeted and delivered to ensure the families who need to benefit do so.

- Who specifically is helped: Although poverty clearly affects children at all stages of life, poverty in early years may have lifetime scarring effects which could be reduced by greater focus on the parents of young children.

- Costs and who bears them.

- Short-term vs long-term horizons: Government should strike a balance between policies which could have immediate tangible effects and those which take time to bear fruit, but where nonetheless early action is required to realise the benefits over time.

In making any choices, government must inevitably grapple with political acceptability. But ministers should not just accept public opinion as given and can, and must, play a positive role in shaping public perceptions, challenging negative stereotypes which pervade conversations around tackling poverty. It should make the positive case for change as it seeks to achieve its opportunity mission.

Conclusions

A new child poverty strategy is both welcome and vital. First and foremost, the government must look at tackling low incomes - both through bolstering the social safety net and supporting people into more and better work. On the former there are obvious early choices to be made on the two-child limit and benefit cap, alongside a longer-term agenda for reform. Moreover, a strategy should address reducing the costs they face and more broadly mitigating the negative effects of those who continue to be trapped in poverty.

To get this right will be a major cross-government endeavour touching on the work of many government departments. In seeking to prioritise the government should be led by the priorities of those with experience of poverty themselves. They should balance longer- and shorter-term plans and they should consider prioritising those most impacted by poverty, such as the youngest children.

Government should be led by the priorities of those with experience of poverty themselves

Finally, the government must make a positive case for bold reform, rejecting some of the prevailing discourse of recent years. To be genuinely transformative, government must ‘grasp the nettle’ and prepare to argue for what it believes in. A government serious about expanding opportunity must be serious about tackling child poverty.

You might also like ...

Restoring security: Understanding the effects of removing the two-child limit across the UK

The government’s decision to lift the two-child limit marks one of the most significant changes to the social security system in a decade.

Gordon Brown on ITV discussing IPPR's proposal to tax gambling companies

Reforming gambling taxation: How to lift half a million children out of poverty

A key priority for the government’s upcoming child poverty strategy should be to remove the two-child limit and scrap the household benefit cap.