Bridge to the future: how to get the NHS through the winter and ready for reform

Article

NHS staff across the country are gritting their teeth. Christmas parties have come and gone, but a more threatening annual tradition looms once again – the NHS ‘winter crisis’. This period, renowned for long waits and increased mortality, is now viewed with grim resignation by patients and policymakers.

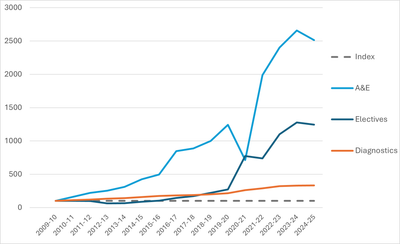

Yet we are facing the ‘coldest winter on record’ in terms of NHS performance. Consider the pre-winter state of the NHS inherited by this government to last time Labour were in power. Comparing the July to Sept monthly average to 2009/10, people waiting for diagnostic scans havetripled, and the number waiting over 18 weeks for elective care is uptwelvefold (Fig 1). Worse, 25 times more people waited over four hours in A&E, affecting over 1.6 million people across the quarter in 2024. Targets are not the point here, safety is – with many facing even more dangerous waits over 12 hours. This is the tragic ‘new normal’ in the NHS.

Figure 1: the pre-winter state of NHS demand and treatment backlogs over time

Monthly average for Q2 (July to Sept): number of people waiting over 4 hours across all types of A&E, waiting over 18 weeks for elective care ‘referral to treatment’, and waiting for diagnostic tests, each indexed to 2009/10.

Source: IPPR analysis, NHS 2024a, 2024b, 2024c

The Secretary of State for Health and Care, Wes Streeting, has rightly called for patient safety to be prioritised over the winter, aligning with every clinician’s instincts to triage and keep the sickest patients safe. However, as official NHS guidance recognises that certain hospitals are regularly treating patients in corridors, clinicians also argue that such measures to ‘scrape by’ another grim winter cannot be consistent with good quality care. Everyone working in the service knows that the status quo is far from the best that the NHS can be. An infant waiting hours in A&E because no health visitor was available to visit, or a man in his 50s facing a foot amputation for uncontrolled diabetes, are failed by a perpetual crisis mentality – and it is the most vulnerable that need services to transform more than ever.

In the short term, the NHS is doing all it can to deliver safe care this winter, including by putting in place thousands more beds, more ambulance call handlers, respiratory hubs, expanding same-day emergency care services as well as virtual wards so more patients can receive hospital-style care at home. It is also ramping up efforts to ensure as many NHS staff and members of the public are vaccinated against flu, Covid-19 and RSV.

But these challenges are deep-rooted and require a long-term focus. In response, Wes Streeting and senior leaders placed NHS reform at the top of the agenda, embarking on consultation for a 10-Year Plan for Health. Promised as the ‘biggest ever conversation’ about the NHS, this process is set to publish a comprehensive plan in the spring. This is a positive sign of intent, aiming to break free of short-term policy and ‘fix the foundations’ of the NHS.

Yet this national conversation is only as valuable as its ability to deliver. Faced with such stark current pressures, it would be a miracle if frontline leaders could think about ten days’ time, let alone ten years into the future. Wes Streeting’s NHS reform plan risks being crowded out by the immediate crisis.

Moreover, frontline morale is far from its best, after surviving not just an unprecedented pandemic, but a decade of rising demand and austerity strain before that. Moral injury is the inevitable consequence of feeling unable to provide the best possible care over the long run. An international review of health workers highlights the impact of short staffing and ill-equipped services on staff wellbeing: “clinicians are increasingly exposed to avoidable moral conflicts engendered by organisational decisions … that compromise care in various ways”. It is unsurprising that more staff are feeling both disempowered and disengaged – a difficult winter could deepen these challenges rather than enabling reform. NHS staff and leaders alike need support and encouragement to prepare a better way forward.

The NHS must pull off a two-part transformation – protecting current services to weather the winter, whilst laying the fertile ground for a 10 Year Plan to succeed in the spring. To deliver this double-act, we call for a ‘bridge to the future’, starting with three steps today. Otherwise, this promising plan may fall on barren soil, leading to deeper crisis each winter to come.

Step 1: clear winter priorities to overcome uncertainty paralysis

At a recent discussion hosted by the IPPR, several senior NHS leaders described a feeling of ‘sitting and waiting’ for the 10 Year Plan, unable to initiate major change in the meantime. A system in which local leaders have long been expected to look ‘upwards’ for instruction generates paralysing uncertainty, disempowerment and leadership churn.

This must be replaced by a clear message from the Secretary of State that leaders should not wait for NHS 10 Year Plan, but get on with reform aligned with the government’s three shifts: towards prevention, digital, and community-based care. Leaders should be empowered to work towards these goals now, with the reassurance that these efforts will not be wasted.

For example, winter safety and long-term improvement both require better integration of data between primary care, ambulances, hospitals, and social care. Effective data reform, such as Greater Manchester’s shared care record, demands careful planning and staff consultation at a local level. This could begin today.

Similarly, the government have stated that spending in primary and community care should increase relative to hospitals, aligning with a strong public focus on fixing the ‘front door’ of the NHS. This should be a firm expectation for 2025/26 financial plans, which will be drafted before the 10 Year Plan is released.

Step 2: local staff engagement to rapidly change the mood music

The 10 Year Plan is laudable for its extensive national-level consultation, speaking with staff across the country and at every level to identify challenges and routes to improvement. Yet meaningful engagement cannot be delivered in a one-off session. It requires ongoing channels to listen and respond, a true shift of power towards frontline staff who often know best, and jointly setting improvement outcomes that everyone can describe and work towards.

All of this means that staff need to be empowered locally, not just at a national level. Every frontline NHS professional can describe a long list of frustrations that waste their time and stand in the way of patient care. Any patient who has had a procedure cancelled due to missing laboratory tests, or spent hours in a waiting room observing the chaos, can speak to this reality. Yet as one regional surgical lead explained; “staff feel far less ownership and ability to improve services in their patch than a decade ago.”

NHS organisations can start rewiring decisions now, which could make a difference today and also get staff prepared for longer term reform. Our research, at the IPPR, identifies a set of immediate reforms to empower the frontline. For instance, NHS staff boards can unlock new ideas and boost morale – as seen in Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospital’s ‘shadow exec’, where staff vacancies have fallen by a quarter since the scheme was introduced. Meanwhile, Northumbria NHS Foundation Trust run weekly staff experience surveys and communicate back on resulting initiatives, from discounted travel to easy-access loans. The trust achieved the highest NHS Staff Survey response rate and the top score on several key indicators across acute and community trusts in 2023.

The ‘twin crises’ of inefficiency and low morale will take time to fully reverse. However, the simple act of listening to staff could change the mood music of the NHS more quickly – and ensure the ‘biggest ever conversation’ turns into true ongoing engagement with staff.

Step 3: a ‘fourth shift’ from national micromanagement to local empowerment

Finally, we must reframe the national conversation now, from a frozen goal of surviving winter to a belief that better services can flourish in every part of the country. This does not mean looking away from the urgent and serious pressures of ensuring patient safety this winter. But a belief in one’s own ability to implement change can be the greatest source of hope and motivation for staff. Despite the efforts of great people across the NHS, staff too often lack belief that they can change the trajectory of the service as a whole.

As part of his long-term vision, the Secretary of State should commit to a fourth shift: from national micromanagement to local empowerment. Such a shift would reassure leaders that the 10 Year Plan will not be about stopping or reversing local transformation plans and success stories, but backing local efforts with money, support, and autonomy. This will help staff move forward now, and lay a more energised and motivated foundation for the plan that is to come.

A ‘bridge to the future’ will be essential to transition from where we are to where we all agree we need to be; a proactive, motivated NHS fit for the future. This transformation will require unlocking the best of leaders and staff to deliver over a decade, not just to weather this season. To take root, change must begin now. Embarking on these three steps today could give the bandwidth to break out of perpetual crisis and prepare the fertile ground to implement the 10 Year Plan when it arrives.