Budget 2020: Level up the economy, step up to the environmental crisis

Article

Rishi Sunak faces one of the most difficult budgets in living memory. The country faces its lowest economic growth rate in a decade, further exacerbated by the expected disruption caused by the coronavirus. At the same time, the government has rightly said it wants to focus resources on reducing inequalities across the country – its so-called ‘levelling up’ agenda.

But this budget also provides the government with an opportunity – to show real leadership on the climate and nature crises ahead of the all-important climate summit to be hosted in Glasgow later this year. IPPR has argued that the government could and should go faster than its current legal target of net zero by 2050. But even this timeframe remains challenging given the government’s insufficient policy action. And with the government set to miss its interim targets in the fourth and fifth carbon budgets, the time for talk is long since past. The government must use this budget to act.

Building on analysis by the UK’s Committee and Climate Change (CCC) and analysis by leading environmental NGOs, we estimate that £33 billion of additional investment is needed every year from now until 2050 if the government is to meet its target. This sounds like a lot, but it amounts to less than we spend on defence every year and is hugely outweighed by the costs of not acting. Moreover, the investment will bring huge benefits to people:from warmer homes to better public transport, as well as helping the government meet its other objectives of levelling up economic performance across the country and raising living standards.

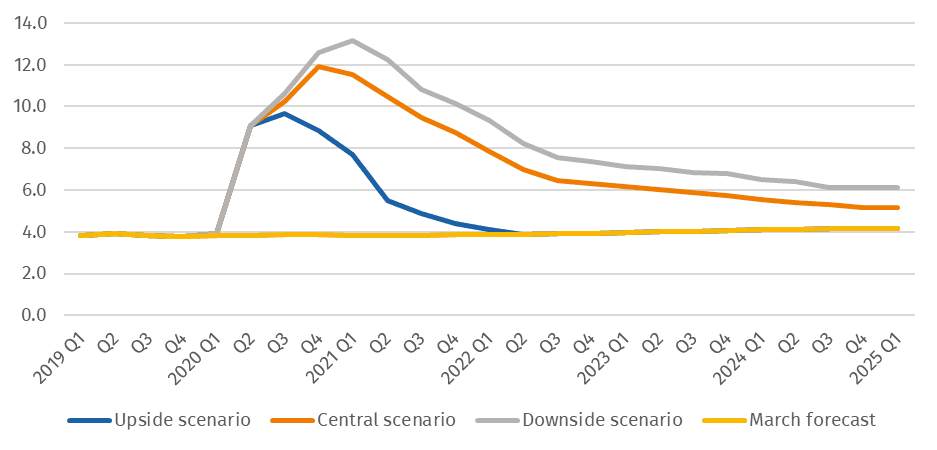

Graph 1 – the government would need to invest £33 billion more per year to hit its own climate target

What does this money need to be invested in? It needs to reach across all sectors of the UK economy, ensuring that the UK runs on renewable energy, industry has switched to mostly carbon-free ways of producing things, houses are well insulated, new forests are flourishing across the UK, public transport is the main means of travel and a large part of consumption is in low-carbon services.

Transport and buildings are two of the most important areas for public investment. Together they account for almost two thirds of the additional investment needed. Transport is the largest contributor to climate change in the UK, responsible for a third of all emissions. And buildings make up a fifth of all emissions.

Decarbonising transport will require about £12 billion additional annual investment. This will support building out and upgrading the railways across the country so that train travel becomes a top-quality and affordable alternative to car and air travel. Investing in our bus networks to increase quality and regularity, helping to boost connectivity in more rural communities and reduce congestion and air pollution in urban areas. Not to mention promoting more walking and cycling, and delivering the infrastructure and incentives required to assist the switch to electric vehicles.

Reducing emissions from buildings will mean a large scale government funded retrofit programme to support making all of our homes more energy efficient, with the added benefit of delivering warmer homes and lower energy bills. Investment will also be needed throughout the 2020s to switch homes away from relying on fossil fuels for heating and cooking. In total, we estimate that about £10 billion additional investment is needed per year for buildings to achieve these objectives.

Three further areas of public investment are important to highlight:

First, nature and farming are also in need of investment. Almost £6 billion each year should be spent supporting environmental land management and nature restoration amongst other things. Addressing the crisis in biodiversity can also significantly increase the amount of carbon absorbed from the atmosphere.

Second, industry too needs to fundamentally change the way it produces products and this will need to be supported by public investment in the coming years. Firms need to find ways to switch from burning fossil fuels in production, to using hydrogen and electricity. The government, in turn, needs to set up a framework for supporting industry in this transition before public investments can take place. This should also include setting up a long-term funding strategy for carbon capture and storage.

Third, and most importantly, people must be at the very heart of the transition and that means a big focus on social justice. We must not repeat the mistakes of the past when whole communities were decimated as a result of the government’s failure to support the communities impacted by the closure of coal mines and deindustrialisation. As previous IPPR reports have proposed, there must be a Just Transition Fund to support communities and enables them to reap the benefits and opportunities that the transition will bring. Future investment may need to be higher but the funding we propose here would make a promising start.

So far, the sums that the government has committed on these issues have been insufficient. In almost all sectors, the Government's election manifesto commitments are far below what is needed. The government plans such as those to invest in upgrading homes, improve public transport and industry efficiency are welcome. But its total climate commitments make up just five per cent of the spending that would be needed to actually achieve net zero by 2050 (Graph 2). Public investment commitments are increasing somewhat towards the end of parliament, but still make up only 12 per cent of what would be needed by 2023-24.

Announced investments would even be insufficient to hit the government’s old, less ambitious, climate target of an 80 per cent emissions reduction by 2050. They constitute only 14 per cent of what would be needed to achieve the government’s old target.

There are those that urge the government to go further and faster than its current net zero target, and we agree. But even on its current target, the government hasn’t yet put in place the investment and policies needed to achieve it. In sum, what is needed is nothing less than a step change of the scale of public investment in the green transition. Such an investment will help us tackle the climate and nature crises but crucially it can also help us secure a better quality of life for all and a fairer and more prosperous economy.

Graph 2 – the government's election manifesto pledges for public investment over this parliament are less than 10% of what is needed to achieve net zero emissions by 2050

NOTES

Methodology: For the previous target (80 per cent reduction by 2050) researchers used Committee on Climate Change (CCC) figures. These had to be complemented with assumptions on the burden sharing between the treasury, business and the public. We followed CCC indications on this wherever possible.

It should also be noted that the estimates by CCC are average yearly costs between 2019 and 2050. As costs are assumed to decline over time, the CCC estimates likely constitute a lower bound in terms of what is needed as upfront spending in 2020. For the new target we also use figures from the CCC. But we slightly adjust these in four cases.

- First, in the transport sector we use Green Alliance et al (2019) figures as these better reflect the need to significantly improve public transport as well as cycling and walking infrastructure. The CCC estimates do not cover this as they only focus on cars, buses and heavy goods vehicles.

- Second, for agriculture and nature we too use Green Alliance et al (2019) figures as the CCC figures do not fully reflect the need to significantly investment in restoration of nature in order to counter biodiversity losses as outlined in IPPR’s work on environmental breakdown.

- Third, we include estimates for a Just Transition Fund. This is absolutely key to enable the transition and make it socially just. A faster transition will require a larger Just Transition Fund.

- Fourth, we adjusted the amount spend in the early 2020s on industry decarbonisation and Bio Energy and Carbon Capture and Storage (BECSS). This is because, as highlighted by the CCC, a framework for public support in these sectors needs to first be established before large-scale pubic investment can take place.

Related items

Planes, trains and automobiles: How green transport can drive manufacturing growth in the UK

Transport is essential to our lives. Unfortunately, it is currently also the largest source of UK domestic carbon emissions.

Regional economies: The role of industrial strategy as a pathway to greener growth

Regions like the North should have a key role to play in the development of a green industrial strategy.

Achieving the 2030 child poverty target: The distance left to travel

On 27 March, the Scottish government will announce whether Scotland’s 2023 child poverty target – no more than 18 per cent of children in poverty – was achieved.