Delivering for children: Why child maintenance needs urgent reform

Article

Children whose parents have separated and struggle to reach a maintenance agreement are let down by child maintenance services which erects deliberate barriers between parents and the support on offer – urgent reform is needed.

Last week we at IPPR Scotland, and our fellow Transforming Child Maintenance project partners (One Parent Families Scotland, Fife Gingerbread, and Poverty Alliance) convened at the Scottish Parliament with other stakeholders, child maintenance experts, MSPs, and parents with lived experience, to report back what we found over the course of the first year of our shared project.

There was unanimity around the table on the urgent need to fix the UK’s flawed child maintenance system, but more specifically the inadequate support on offer through the Child Maintenance Service (CMS).

The parents in attendance made an especially valuable and powerful contribution to the event. Parents detailed how the CMS makes administrative errors, misunderstands situations, and even asks parents to investigate, and evidence claims, where this might carry risk to safety.

Other stakeholders spoke of the need for significant reform of the existing system which places children and their needs at the centre of establishing working arrangements, while recognising durable maintenance arrangements require a balanced approach between parents which recognise mutual responsibility and fairness.

Child maintenance can help keep children out of poverty

Family separation can be one of the most difficult periods in children’s and parents’ lives. Just one of the reasons this can be potentially traumatic for all involved comes down to money. A situation made worse by the reality that reaching a durable maintenance arrangement, to help secure the financial security of children, can be incredibly challenging.

As part of this project, we at IPPR and One Parent Families Scotland have spoken with paying parents and receiving parents, as well as polled parents in Scotland, analysed official data, and engaged with experts in child maintenance. In our analysis of DWP data, it was clear that children living with one adult face a higher risk of poverty than children living with two. We also found that child maintenance, when agreed and paid, can have a genuine anti-child poverty impact.

We found child maintenance reduces the number of children in poverty in the UK by 140,000.

Among children who receive maintenance, the child poverty rate is 30%, when it would be 40% without maintenance. In aggregate, we found child maintenance reduces the number of children in poverty in the UK by 140,000.

Polling we commissioned that took place over March confirmed that parents agree that child maintenance should continue to play a role in ensuring a child's financial security moving forward.

Does the current child maintenance system deliver for children and parents?

However, we found that the system as it currently operates, fails far too many children, leaving them to suffer without any maintenance arrangement in place. This is the result of intentional barriers which have been erected between parents and the support on offer through the Child Maintenance Service.

Reforms made in 2012 to the existing maintenance system aimed to create a smaller, more efficient CMS which would reduce costs to the state by shifting separated families from statutory arrangements into private family-based arrangements. These private arrangements were presented as optimal for both children and parents on account that parents who had private arrangements in place cited higher levels of satisfaction than those with statutory arrangements. This seemingly ignores the fact that those parents who agreed satisfactory private arrangements required least assistance by virtue of arriving at a resolution outside the statutory system.

Rather, these reforms appear to prioritise taxpayer savings over the financial security of children and did so by introducing fees and deductions to maintenance payments paid by parents for utilising the services the CMS provides.

What the reforms did in practice

Among those services the CMS provides, ‘Direct Pay’ is the more hands-off intervention by the state. The CMS calculates payments owed, and leaves parents to transfer funds between themselves. Parents are left to log and inform the CMS where arrangements are unfulfilled. In essence, Direct Pay functions as a final opportunity for parents to establish a family-based arrangement and avoid moving to ‘Collect and Pay’.

Under ‘Collect and Pay’, the CMS calculates and manages payments - compelling paying parents to transfer funds from their earnings, benefits, shares, or pensions. Following the 2012 reforms, paying parents are charged a 20% surcharge on top of their maintenance payment, and payments received by children through receiving parents are deducted 4%; financial deductions that ultimately amounts to denying children money.

This has amounted to a system of gateways making it harder to access oftentimes crucial state support to help establish maintenance payments.

Evidence of a failed experiment

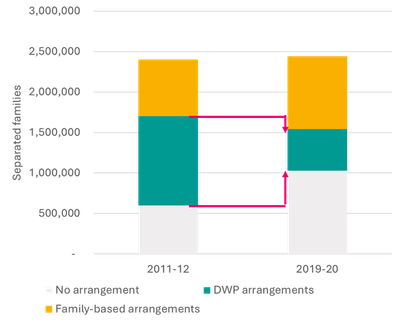

As Figure 1 shows, more than one million separated families went without a maintenance arrangement as of 2020, compared with around 600,000 in 2012 before the reforms took hold. Not only has the attempt to squeeze families out of DWP arrangements (shown in green) clearly worked, but this squeeze has also resulted in far more families ending up with no arrangement (grey) than with family-based arrangements (yellow) as the reforms intended.

Figure 1: The 2012 reforms to the child maintenance system drove families out of statutory arrangement but with very limited growth in family-based arrangements

Source: Author's analysis of National Audit Office (2022) 'Child maintenance: The Department for Work & Pensions, report. https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/child-maintenance/

That the reforms were twice as effective at driving families away from child maintenance arrangements as they were driving them towards family-based arrangements is a damning indictment of the system’s design and leads to more children suffering in poverty.

Most of the parents polled in March agreed (51%) that fees only exacerbate conflict and adversely affect the children, while only 13% disagreed. Meanwhile almost half of the parents (49%) agreed that the UK government should not adopt a punitive approach towards parents who cannot reach an agreement without the help of the CMS, as compared with 13% who disagreed.

As an experiment in whether withholding support would encourage family-based arrangements it has comprehensively failed.

Parents’ experience of the Child Maintenance Service

For parents who have experience interacting with the CMS, many report their interactions to be a generally negative experience, with concerns over the proficiency of the CMS, and insensitivity in how it engages parents seeking support.

These deficiencies simultaneously drive parents away from accessing statutory support, for fear the support on offer is more trouble than it is worth, while undermining existing maintenance arrangements between parents and children.

These criticisms, come through strongly among both paying and receiving parents.

One parent recalled: “Calling the Child Maintenance Service is like calling a mobile phone company, they are unsympathetic and get angry and cut into the conversation…they should understand this is about your life and your child’s life, not a phone contract.”

Parents complained of phone calls to the CMS being subject to long waits, unanswered questions, and inconsistent records of case history, as well as missed or incomplete payments, and a slow process for collecting much needed unpaid maintenance. Parents also felt that CMS staff lacked the necessary training in how to deal with domestic abuse, particularly in cases where ‘no contact orders’ were in place, and it would be dangerous for separated parents to correspond.

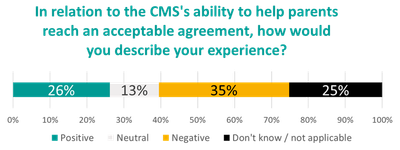

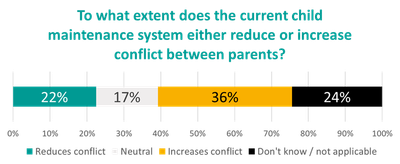

Looking at our polling, among parents in Scotland with experience of the CMS – 35% rate their experience using the CMS as negative (Figure 2); and 36% believed the current maintenance system increases conflict rather than reduces it (Figure 3). As shown in Figure 3, notably more than say it was a positive experience or reduced conflict.

Figure 2: Polling results – ‘In relation to the CMS's ability to help parents reach an acceptable agreement, how would you describe your experience?’

Source: Results for subsample of poll commissioned by IPPR Scotland and conducted by Diffley Partnership of 210 parents in Scotland with experience either paying or receiving child maintenance

Figure 3: Polling results - 'To what extent does the current child maintenance system either reduce or increase conflict between parents?'

Source: Results for subsample of poll commissioned by IPPR Scotland and conducted by Diffley Partnership of 210 parents in Scotland with experience either paying or receiving child maintenance

Worsening parental conflict within the current child maintenance system

Another major issue with the CMS and the way child maintenance works relates to how mistrust between parents is exacerbated by perceived unfairness from both parents within the current system. This not only acts as a barrier to establishing arrangements in the first place, but it also heightens conflict between separated parents.

For example, the calculation of maintenance paying parents are due to pay is determined by a formula written into primary legislation in 1998. Its assumptions around what is affordable and how much should be paid at various income thresholds have not kept pace with changing costs and incomes.

There is also no self-support allowance for paying parents, as utilised in many European countries, which would approximate a minimum income for paying parents to afford a basic standard of living before child maintenance is paid out to children. And where affordability mechanisms exist, they are flawed: the 25% income rule demands that only when the income of a paying parent has increased or decreased by 25% can there be a re-assessment on how much maintenance a paying parent can afford to pay.

Perhaps the most damning feature of the system is the fact that in some instances parents in conflict report that their former partners threaten them with the involvement of the CMS. That CMS arrangements can be weaponised in this way shows the strategy of incentivising parents into family-based arrangements has effectively created a hostile environment.

Looking towards a better system for children

It seems clear we need to shift from this hostile environment to a system that helps parents establish arrangements, with the state playing a more active role in safeguarding the financial security of children in separated families.

Indeed, our March polling shows that most parents agreed the UK government should go beyond the current CMS model and underwrite children’s financial security, like the Nordic nations which guarantee maintenance payments so that a child is never left to suffer without crucial support.

Parents supported such a scheme in two cases: if the paying parent failed to make payments, the state would step in, pay the maintenance due, and try to recover money from that parent (55% agree), or the paying parent did not have enough money to meet the minimum amount, in which case the state would cover the difference (59% agree).

This goes against the desire of several UK governments for a hands-off approach when dealing with maintenance arrangements. Instead, the primary focus of the CMS should be on protecting the financial security of children and recognising the need to support rather than coerce parents into productive post-separation relationships.