Developed economies must be bolder to deliver a fair transition for transport

Article

At COP27 and COP15 global leaders had the opportunity to set out a new vision for transport, one that would protect and restore nature, rapidly reduce carbon emissions and be fair to all. By over emphasising the role of electric vehicles in the future of the transport system, they are limiting the progress we can secure this decade and making it harder to keep 1.5 degrees within reach. This blog shines a light on UK and Germany in particular and argues that both must show bolder leadership on this agenda and commit to a transformative, equitable vision for transport.

As 2022 draws to a close, it is a moment to take stock of progress in global efforts to address transport’s contributions to the climate and nature crises, and the implications this has for how we live and how fair our societies will be in the future.

To start with the obvious, collectively, we aren’t doing enough to tackle emissions from transport. The sector is responsible for around 17 per cent of global emissions and is the fastest growing source of emissions. Most transport emissions are from road passenger transport (circa 45 per cent in 2018) and road freight (circa 29 per cent). The Covid-19 pandemic led to an initial reduction of transport emissions, but quickly rebounded – jumping by 8 per cent in 2021, compared to 2020.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) laid out the challenge for transport earlier this year, arguing that this sector is likely to be the most difficult to decarbonise. This is due to continued growth in the global demand for transport, particularly in developing and emerging economies, combined with the historic lack of progress in addressing the structural challenges that drive the growth in emissions within OECD countries.

Responsibility for transport emissions is not shared equally. Around 10 per cent of the world’s population are responsible for 80 per cent of the distance travelled by ‘motorized passenger transport’, with most people hardly travelling at all.

Transformative change is needed. But have world leaders been up to the challenge?

COP27 and COP15 fail to lead the way to a desirable transport future

Unlike COP26, there was no dedicated ‘transport day’ at COP27; sustainable transport became one of many themes discussed as part of ‘solutions day’. This provided limited space to make progress on COP26’s transport declaration, which majored on the role of electric vehicles and had only one sentence on wider system change:

We recognise that alongside the shift to zero emission vehicles, a sustainable future for road transport will require wider system transformation, including support for active travel, public and shared transport, as well as addressing the full value chain impacts from vehicle production, use and disposal (Gov UK 2021).

Contrast this ‘recognition’ of the need for wider change with the ‘Breakthrough Agenda’ goal for road transport, which sets a timebound target for zero-emissions vehicles to become the new norm by 2030, and be accessible and affordable to all.

We must radically reduce demand for road transport, including electric vehicles (EVs). EVs must also become the global norm for new car sales by 2030. Recent research shows that, to keep 1.5 degrees in reach, the absolute limit on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars is 315 million, yet car manufacturers still have plans to sell up to 463 million more ICE vehicles than this – an overshoot of up to 147 per cent.

COP15’s goal to deliver “the shared vision of living in harmony with nature” cannot be fulfilled without reducing transport’s impact on key habitats and species. Recent analysis shows the scale of the risk that planned transport infrastructure brings to biodiversity – it will impact the habitats of nearly 2,500 bird, amphibian and mammal species of conservation concern, will cross over 60,000km of the world’s protected areas or key biodiversity areas and release 883 million tonnes of carbon from removed trees and vegetation. Whilst more road and rail infrastructure may be needed in places, its impact on nature must be better considered in decision making and project design.

Developed economies should lead the way in addressing these challenges. However, in both Germany and UK we see ongoing commitments to subsidising road transport and new major road infrastructure projects. The climate and nature impacts of the UK’s road investment strategy have been widely challenged, as too have the ongoing investment in expanding Germany’s superhighways.

The case of the UK and Germany: shared legal mandates alongside limited progress and a clear struggle to think beyond the existing car-dependent transport system

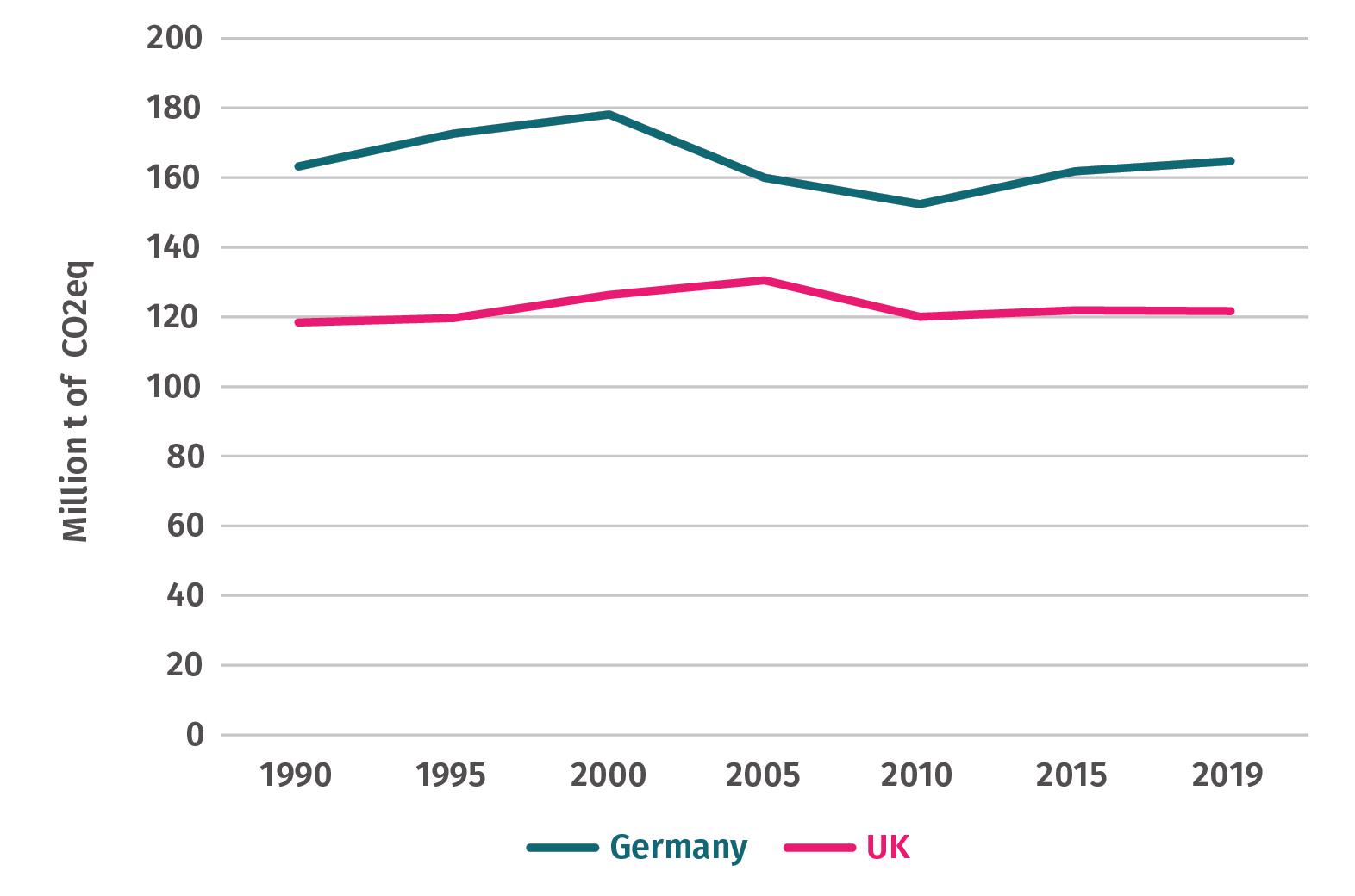

Whilst UK and Germany have both made progress in reducing their emissions generally, transport emissions have remained largely unchanged over recent decades (see figure 1). In the UK, transport is the number one source of greenhouse gas emissions; in Germany it now sits in third place.

Figure 1: Transport emissions in Germany and the UK have barely changed in almost 30 years

Greenhouse gas emissions from transport in Germany and the UK, 1990 to 2019, measured in carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2eq)

Source: IPPR analysis of Our World in Data (2022) based on Climate Analysis Indicators Tool (CAIT)

Both countries have set out legal frameworks and targets to deliver net zero. Germany aims to reach net zero by 2045 and cut emissions by at least 65 per cent by 2030 compared to 1990. The UK is targeting net zero by 2050, and a 78 per cent cut compared to 1990 levels by 2035. Both have plans to reduce transport emissions as part of meeting these goals, but are reliant on a rapid shift to EVs for most of these emission savings, and lack clear targets for demand reduction.

The UK and Germany have a common challenge; they need to make progress in shifting travel behaviours. Yet, they undermine their endeavours with a lack of joined-up thinking, particularly in fiscal policy. Germany’s efforts to make public transport more affordable have received global attention and inspired calls for similar levels of ambition in the UK. Undermining these efforts, however, is their cut in VAT on fuel until 2024. Likewise, in the UK, fuel duty has been frozen since 2011, and was cut during 2022/23. As well as sending the wrong signals, analysis of the German cuts demonstrates that it is the wealthiest, who drive more, who benefit most from reducing the cost of fossil fuels.

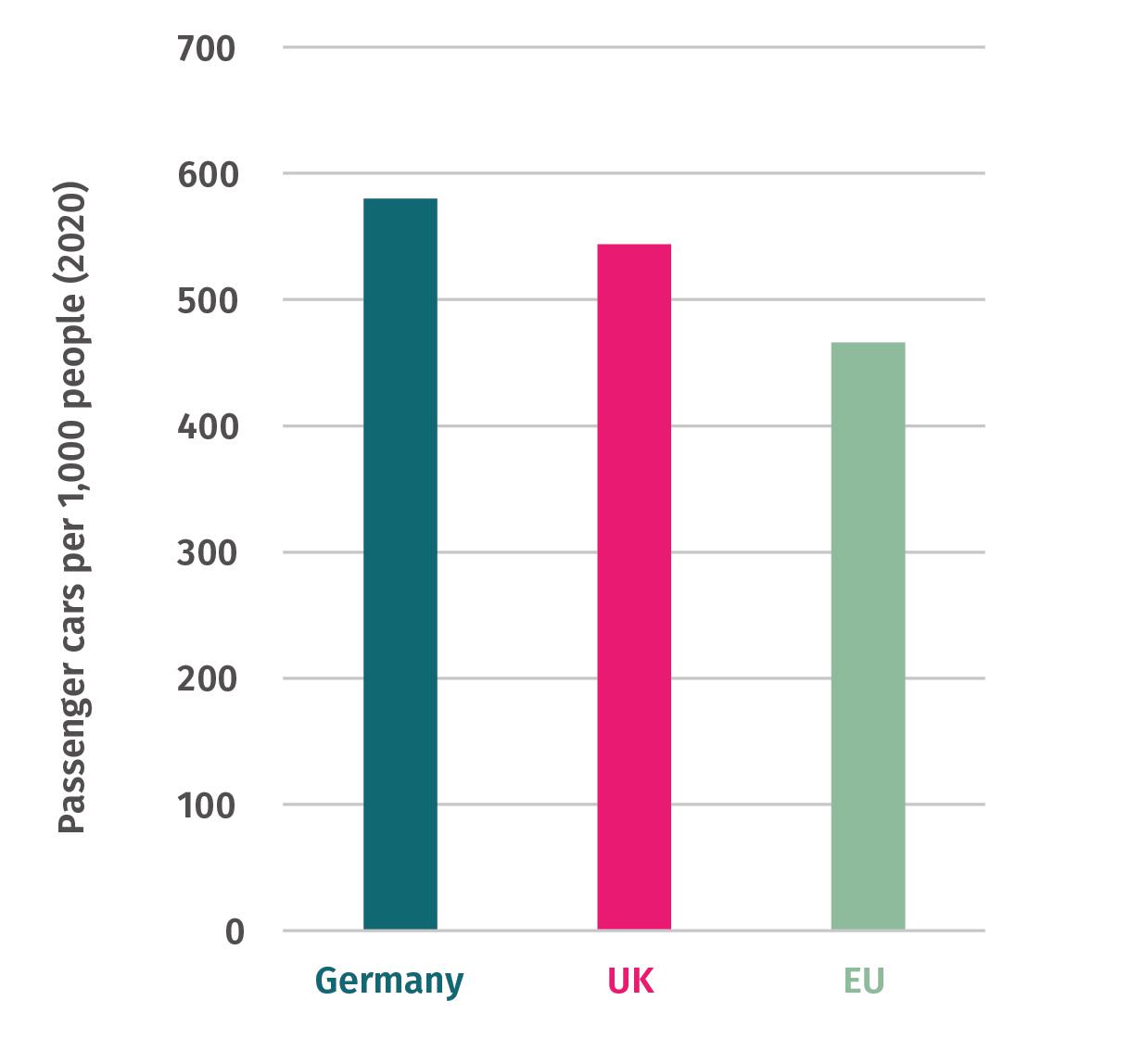

As IPPR’s research shows, the UK government is yet to address the risks to society and the environment if levels of car ownership climb in line with predictions. These challenges are even starker in Germany, which has a current car fleet over 48 million, circa 10 million more cars than the UK. Germany and the UK both have a higher number of passenger cars per 1,000 people than the EU average (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Germany has more cars per capita than the UK; both have higher cars per capita than the EU as a whole

Passenger cars per 1,000 people in Germany, the UK and the EU (2020)

Source: IPPR analysis of acea (2022)

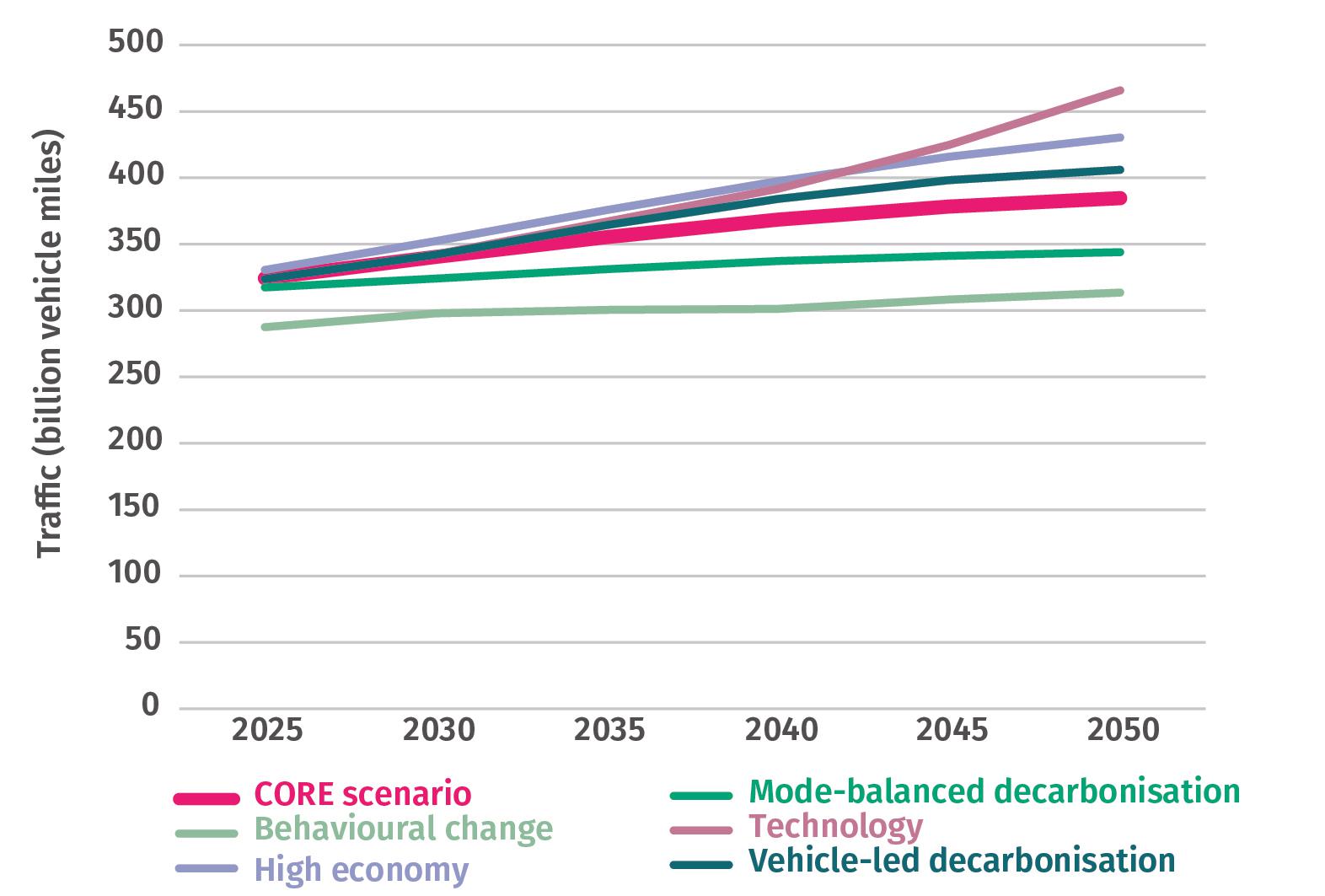

Recent updates to the national road traffic projections show how far the UK has to go in addressing the underlying causes of increasing traffic. Against a backdrop of significant uncertainty, the national road traffic projections for 2022 provide seven scenarios for road traffic in England and Wales. All scenarios show an increase in traffic (see figure 3). A core scenario, based on ‘firm and funded’ government policy, would see an almost 20 per cent increase in traffic between 2025 and 2050. The ‘technology scenario’ presents the highest traffic growth (54 per cent), driven by a high and fast uptake of autonomous vehicles and electric vehicles; the ‘behaviour change’ scenario presents the lowest (8 per cent), with a wider societal shift away from car use including through increased home working and reduced driving license uptake amongst young people.

Figure 3: Road traffic in England and Wales is projected to increase in all scenarios

National road traffic projections for England and Wales (2025-2050), select scenarios

Source: IPPR analysis of Department for Transport (2022)

These UK projections come with the caveat that the predictions “are not necessarily desirable”. It has never been clearer that ever-increasing car use in developed economies is incompatible with achieving climate targets and undesirable for its wider social and environment costs.

Delivering a fair transition for transport

2022 has seen a growing awareness of the need for transformative action, marked by missed opportunities to deliver it. So what should global leaders and national decision makers focus on in 2023 and beyond?

The UK lacks a clear direction for the future of transport, and clearly, collectively, global leaders do too. It is only by setting out what a desirable, equitable transport system will look like that we can ensure that we get there and that the pathway to net zero is fair.

Establishing this vision, and the action required to deliver it, cannot and should not be done behind closed doors by traditional transport decision makers. New institutions and governance frameworks are needed to ensure a fair transition and build a broad support for climate policymaking. In particular, citizens need to be provided with the support, opportunities and power to shape their communities and a fairer, greener future.

Through our research, we have heard how communities across the UK want their local councils and the Scottish, Welsh and UK governments to respond to the climate and nature crises (see table 1). They point to structural changes that ensure that everyone has good transport options and, where possible, can meet their needs locally through better digital access and planning reform. Crucially, the public have also told us that they want a clear shift in priorities away from cars towards nature and people’s health and wellbeing. This must include ensuring that we have a transport system that is safe for all including women and vulnerable groups.

Table 1: Principles for a future transport system as defined by the citizens’ juries convened as part of IPPR’s Environmental Justice Commission

Provide people with good transport options |

|

Make it possible for people to access what they need locally |

|

Shift priorities away from cars to nature and people |

|

The challenge for the UK, Germany and all developed economies is to lock in their climate commitments by delivering significant reductions in transport emissions within the 2020s. This will be made easier by delivering rapid and deep reductions in transport demand. In doing so, they must make ‘fairness a foundation’ – recognising that the wealthiest have contributed disproportionately to higher emissions and have the highest potential to make reductions without impacting on their living standards or wellbeing.

This blog was supported by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES), a non-profit German foundation funded by the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Related items

Rule of the market: How to lower UK borrowing costs

The UK is paying a premium on its borrowing costs that ‘economic fundamentals’, such as the sustainability of its public finances, cannot fully explain.

Restoring security: Understanding the effects of removing the two-child limit across the UK

The government’s decision to lift the two-child limit marks one of the most significant changes to the social security system in a decade.

Building a healthier, wealthier Britain: Launching the IPPR Centre for Health and Prosperity

Following the success of our Commission on Health and Prosperity, IPPR is excited to launch the Centre for Health and Prosperity.