Elections in hard times

Article

Political scientists in the past half-century have increasingly de-emphasised the role of ideological commitments and policy promises in accounting for voting behavior, in favour of an alternative account in which voters simply assess how the nation is faring - particularly in respect of the economy - and vote to retain the incumbent government if things are going well and to replace them if things are going badly. This so-called 'retrospective voting' model makes fewer unrealistic demands of voters, it seems to provide a modicum of democratic accountability, and it does a better job of explaining election outcomes than the traditional ideological model.

Retrospective voting

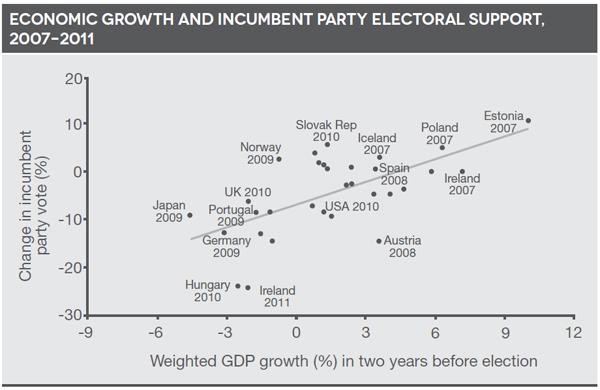

So to what extent can simple 'retrospective voting' account for election outcomes in the current Great Recession era? The figure below shows the relationship between economic growth and the outcomes of 31 parliamentary elections conducted in OECD countries between 2007 and early 2011.

In each case, the figure relates increases or decreases in the incumbent party's vote share since the previous election to real GDP growth in the two years leading up to the election.

The relationship portrayed in the figure is generally consistent with a rather simple model of retrospective voting. Citizens in OECD countries tended to reward their governments when their economies grew robustly and to punish their governments when economic growth slowed. The magnitude of these rewards and punishments was substantial, with differences in expected vote shares of almost 23 percentage points over the observed range of GDP growth. (The relationship is bolstered by two cases in which substantial declines in GDP were compounded by austerity policies and scandals - Hungary in 2010 and Ireland in 2011. However, even if these cases are omitted there is a strong positive relationship between economic growth and incumbent vote shares.) While there is obviously much more to elections than economic voting - scandals, social concerns, wars and international crises, evaluations of the competence and charisma of party leaders, stirring speeches, and on - it is clear that elections in the wake of the Great Recession were significantly influenced by voters' consistent inclination to reward or punish incumbent governments based on economic growth rates in the months leading up to an election.

The pattern of election outcomes presented in the figure suggests that real GDP growth of about 4 per cent a year would be required for an incumbent government to maintain its vote share. In 2005, 2006, and 2007, even before the onset of the Great Recession, the average real GDP growth rate in OECD countries was a bit less than 3 per cent. The discrepancy between these figures suggests that, even in normal economic times, incumbent governments are likely to experience a gradual erosion of electoral support. Thus, the behaviour of voters seems well-calibrated to ensure frequent turnover in office, while still providing some incentive for incumbents to do whatever they can to produce economic growth.

All in the timing

The timing of electorally significant economic growth suggests another potential failure of accountability. My analysis suggests that voters are mostly focused on economic conditions in the immediate run-up to an election rather than on the incumbent government's overall economic performance; the measure of 'weighted GDP growth' employed in this analysis attaches twice as much weight to growth in the year just before the election as to growth in the preceding year - and no weight at all to growth earlier in the incumbents' tenure. Thus, electoral incentives to produce economic growth seem to be largely absent through much of an incumbent government's term in office.

One important implication of these patterns is that incumbent governments are, to a significant degree, at the mercy of the electoral calendar. A reelection campaign in the middle of an economic boom may provide a convenient opportunity for an incumbent government to renew its popular mandate; but facing the voters in the midst of an economic downturn is likely to be hazardous to an incumbent government's survival, even if the downturn is global in scope.

The contrasting electoral fates of the socialist governments of Spain and Portugal provide a concrete contrast between lucky and unlucky election timing. The Spanish government led by Socialist Workers' party (PSOE) prime minister Jos? Luis Rodriguez Zapatero faced the voters in March 2008, just before slowing economic growth in Spain (and in the OECD as a whole) slid into full-blown recession. The result was a slight increase in the governing party's vote share, and the Spanish socialists remained in power for almost four more years. The Portuguese socialist government of Jos? S?crates was less fortunate; its mandate expired in September 2009, just after the Great Recession reached its nadir in Portugal (and in the OECD as a whole). As a result, the Portuguese socialists lost their parliamentary majority and limped on as a minority administration for two years, before losing power completely in 2011.

It might be tempting to interpret the Portuguese result, considered in isolation, as a rejection of socialism as an ideology or as an economic policy prescription. However, in light of the fact that a similar socialist government in Spain cruised to re-election just months before the Great Recession took hold, it seems much more plausible to see the Portuguese result as simple punishment of the 'ins' following a period of prolonged economic distress. Indeed, both of these very different election outcomes are almost perfectly consistent with the overall relationship between economic growth and recent election outcomes in OECD countries.

A turn to the right?

More generally, however, there is surprisingly little evidence of any systematic electoral shift in favour of either left-wing or right-wing parties in response to the Great Recession. Ten of the 21 incumbent governments that faced the voters during the worst three years of the downturn (from mid-2008 through mid-2011) were left-of-centre (or, in the case of Israel, a centre-left coalition); on average, their vote shares declined by a very substantial 7.7 per cent. However, this average vote loss is inflated by the disastrous losses suffered by left-wing governments in Hungary in 2010 (-23.9 per cent) and Ireland in 2011 (-24.1 per cent), which seemed to have much more to do with scandals and austerity programmes than with leftist ideology. The remaining eight leftist governments suffered an average vote loss of only 3.6 per cent. By comparison, the seven right-of-centre governments that faced the voters during this period suffered a virtually identical average vote loss of 3.5 per cent. While left-of-centre governments in Portugal, the US, New Zealand and Britain suffered significant losses, so did right-of-centre governments in Iceland, Japan and Greece.

Centrist coalitions actually fared worst of all, with incumbent coalitions in the Netherlands, Austria, Germany, and Finland suffering an average vote loss of 12.7 per cent. Taking simultaneous account of incumbent ideology and economic conditions in a systematic statistical analysis of all 21 elections reinforces the conclusion that ideology had no significant impact on the electoral fate of incumbent governments during the Great Recession.

Elections in the US and France

In 2012, the US economy seems to be rebounding, and Democrats' electoral prospects are correspondingly brighter than they were in 2010. If economic growth between now and election day matches the current OECD forecast of 2 per cent - and if the statistical relationship observed in recent parliamentary elections can be stretched to apply to a presidential election - then Obama should be expected to win almost exactly 50 per cent of the vote, despite having presided over a prolonged economic slump in the first half of his term.

In France, where recent economic growth has been slower, a similar analysis suggested that incumbent president Nicolas Sarkozy would win 48 per cent of the vote in the run-off against socialist challenger Fran?ois Hollande and thus lose power - which is exactly what happened. However, a victory for Hollande does not necessarily constitute a mandate for socialism in France, any more than S?crates's defeat constituted a repudiation of socialism in Portugal. Elections are mostly not about ideology.

Interpreting election outcomes is not merely a scholarly pursuit. For better or worse, perceptions of what voters had in mind in casting their ballots can shape practical political discourse and action. American political culture in the 20th century was significantly shaped by the conventional belief that the 1936 election constituted a referendum on the role of the federal government in the American economy and society. More recently, an over-interpretation of the ideological significance of Barack Obama's historic victory in the 2008 presidential election - a victory portrayed by enthusiastic pundits as a 'rebirth of American liberalism' - may have influenced the Democrats' decision to pursue an ambitious legislative agenda unrelated to the economic crisis in the first half of Obama's term.

Conservatives and the economic crisis

When understandings of this sort are mistaken, political trouble may ensue. Perhaps not surprisingly, election winners are especially prone to over-interpret their victories as ideological triumphs. For example, Conservative party leader David Cameron hailed his party's 2010 election victory as a mandate for 'new economic management', despite the fact that opinion polls at the time found solid majorities of Britons in favour of aiding troubled industries, significantly increasing government spending, and providing financial support to troubled banks.

For the first six months following Cameron's election the British economy grew fairly robustly; Britons displayed a good deal of patience with the Coalition government's austerity measures, and US treasury secretary Timothy Geithner pronounced himself 'very impressed' with Cameron's strategy for dealing with 'problems not created by this government.'

However, less than two years into Cameron's term, and with little sustained economic growth since late 2010, his 'mandate' seems to be wearing thin. Only 30 per cent of Britons in an early April YouGov poll say he would make the best leader for Britain, and only 32 per cent support the Tories (against 42 per cent for Labour). Despite these political setbacks, the Cameron government seems resolved to maintain its stringent austerity measures through the next general election. If the British economy rebounds, today's hard times will be long forgotten by then and Cameron's ideological bet should pay off handsomely. But if austerity fails to produce prosperity in the months leading up to the next election, that will be a problem 'created by this government' and Cameron will likely be a one-term prime minister.

Cameron led a conservative opposition party to victory at the polls in the wake of the Great Recession. However, he - and we - would do well to bear in mind that his triumph had much less to do with ideology than with slow economic growth under Labour, and that the economy, not ideology, will mostly determine his government's fate. In periods of economic crisis, as in more normal times, voters have a strong tendency to support any policies that seem to work, and to punish leaders regardless of their ideology when economic growth is slow.

- This is an edited version of Larry Bartels' essay for Juncture - download the full article.

Related items

Women in Scotland: the gendered impact of care on financial stability and well-being

Women in Scotland are far likelier than men to take on childcare and other caring responsibilities, which puts them at an economic disadvantage.

Citizenship: A race to the bottom?

The ability to move from temporary immigration status to settlement, and ultimately to citizenship, is the cornerstone of a fair and functional immigration system.

Reflections on International Women's Day 2025

In a world that currently seems increasingly dominated by ‘strong man’ politics and macho posturing, this International Women’s Day it seems more important than ever to take stock of where we are on the representation of women in politics.