Flights of fancy: Making polluters pay

Article

This blog assesses options for fairly taxing aviation, including considering proposals for a ‘frequent flyer levy’ alongside changes to APD – arguing that taxing private jets properly is a quick and effective option in the near term.

About our future-facing tax blog series from guest author Mark Lloyd

A budget and spending review loom in the autumn, posing some choices for the new government.

It is right that the government’s clear stated preference is to improve the public finances by growing the economy, but the new chancellor will surely also need to consider options to improve the fairness and sustainability of the UK tax base, and to find the resources needed to begin the repair job now. The UK’s tax system is overdue for improvement, is not fit for the future economy, and successive administrations have dodged the hard choices on tax reform.

In this series of IPPR blogs, Mark Lloyd puts forward some realistic, implementable reforms for this parliament to set the tax system up well for the future, to meet the government’s wider policy objectives, and to raise revenues.

Mark Lloyd is an economic policy specialist who has advised ministers on tax policy and industrial strategy in HM Treasury and 10 Downing Street. He is currently working in the international development sector, where he supports both national and local governments in developing countries on a wide range of policy and delivery issues. He is writing these discussion papers for IPPR as a guest author.

1-in-10 flights from the UK is via private plane but they get an easyride on tax. It's time to change this and take a step towards longer term action on polluting, private jets

This blog series is exploring the case for new tax bases that respond to social, economic or technological changes. With Budget fast-approaching, it’s the big-ticket revenue raisers that are in the spotlight at the moment. The government has said it won’t increase taxes on working people and wants to ensure that those with the broadest shoulders pay their fair share, but this leaves relatively few areas to look for revenues.

Aviation taxation is a case in point. Globally, air passenger numbers continue to grow, and are forecast to double by the 2050s at the same time many countries aim to achieve ‘net zero’ – something which is likely to require a decrease in air travel. This lies behind recent calls for a ‘frequent flyer levy’ to reduce the demand for air travel.

While UK passenger numbers have not yet returned to their pre-pandemic peak, and a frequent flyer levy looks some way off, one trend in UK air travel is particularly noticeable: the rise of private aviation. This piece looks more closely at how air travel is taxed in the UK, and the options to raise more in the near term.

Flying high

Aviation taxation is an area that raises almost £4bn a year for the Treasury, but where the current approach bakes in some glaring inequities in taxation, and fails to be proportional to emissions. This is true of the way that business class flights are taxed relative to economy class, but especially true for how flights in private jets are treated.

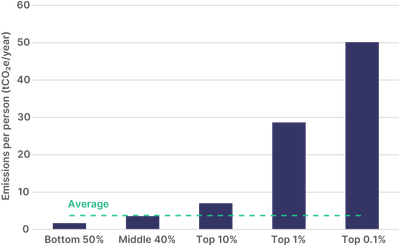

When 70 per cent of UK flights are taken by richest 15 per cent of people, with a huge cost in terms of carbon emissions, it intuitively feels fair to ask those who fly more often, and produce more emissions when they do, to pay more. The rise in private jet use from the UK provides a platform for action.

The UK is the Europe’s biggest private jet polluter. A private jet takes off in the UK every 6 minutes. It is an amazing fact that 1 in 10 flights from the UK is now via private plane, and these can be up to 14 times more polluting per passenger than a standard flight.

But these highly polluting flyers are getting an easy ride when it comes to taxation.

The main UK tax on flying is Air Passenger Duty. It is another amazing fact that the current APD level on air tickets for some private jets means that these users pay less in APD than ‘ordinary’ passengers, and indeed sometimes pay nothing at all.

This is unfair, but it’s also an environmental policy problem. According to research from ‘Possible’, for a flight from London to New York, the implicit carbon price per tonne of emissions is £96 for a passenger in economy class, £72 for a business class passenger, and just £52 for a first-class passenger.

It is even worse when you factor in private flights: A passenger making the same flight by private jet would pay just £13 per tonne in a medium size private jet and £24 in a large private jet. This shows that the current APD structure needs to be revisited.

And this is not just about small planes. There is evidence that an increasing number of private flights with very few passengers on board are taking place in big, commercial-sized aircraft, with an average of perhaps just 2-5 passengers on board. These are especially polluting.

Despite this, the previous UK government chose to freeze APD for domestic private jet flights, while raising it for commercial flights.

Here is a quick guide to some changes that should be made to APD structures and rates to tax private jetting more fairly:

- APD is a per-passenger charge that essentially differentiates between: 1) Domestic flights, 2) Short haul flights and 3) Long haul flights. It charges more for longer distances. It also recognises the difference between ‘economy’ class, ‘business’ class, and has some limited provisions to charge certain types of private jets a higher rate.

- However, the current tax rate for flights in smaller aircraft (currently defined as those with fewer than 19 seats) should rise substantially. This should especially be the case for domestic flights, where a clear alternative form of travel is available.

- The definitions used to differentiate ‘private jet’ journeys should be revisited and tightened up to capture 1) smaller aircraft, below the existing minimum weight threshold of 5.7 tonnes, and 2) larger commercial aircraft that have been ‘converted’ for use as private jets, by reference to available space and seating capacity. These are some of the most polluting and expensive flights. Users should pay much more tax.

- The tax base should be expanded to cover passenger helicopter flights (while retaining clear and obvious exemptions for emergency services like air ambulance and coastguard).

If the above changes were combined with gradual action to improve the fairness of the charging structure of APD for business class flights, it could bring in significant revenues in the coming years.

Of course, wider action on air travel is going to be needed to meet Net Zero targets – this blog does not in any way imply that these actions would be sufficient to reduce demand for air travel by 75 per cent, or to strip 5000 tonnes of CO2 out of UK emissions.

However, the above represents a quick and relatively easy way to correct some glaring imbalances in the aviation tax system, and raise revenues quickly, while the picture on sustainable jet fuels and alternative technologies becomes clearer.