How to conduct fiscal policy in the next parliament

Article

In recent years, the notion that government tax and spending policy should be constrained by self-imposed rules has become the established norm. Yet while the government that emerges from the 2015 general election should certainly have a set of fiscal rules, they should substantially differ from the current ones, and indeed from those used by the previous Labour government.

The next general election may be two years away, but it is already a pretty safe bet what the winning formula will be. The party that can convince the electorate it will deliver sustained growth while also putting the public finances on a sounder basis will have a very good chance of forming a government.

Both elements of the winning formula are equally important. A plan to boost the economy that is fiscally incontinent would be irresponsible, scare the markets and lack credibility with voters. But, as this essay will argue, fiscal policy that is overly constraining and which is not geared towards assisting economic growth quickly becomes self-defeating.

Instead, as I have recently argued elsewhere, a new fiscal policy is required - one which has at its heart two principles that can still appear counterintuitive to the popular imagination. This is despite their long pedigree (going back to Keynes), and despite the fact that the alternative - austerity - has clearly failed to bring the UK out of its economic slump.

The first principle, simply stated, is that it is sensible for the government to spend a bit more and tax a bit less when private sector economic activity is weak and demand is low. This might increase public debt, but if - as we have seen in recent years - the economy is stuck in a rut, then the government, and only the government, can get it moving again. If this true, then it is vital that the second, converse principle is adhered to strictly. This principle states that when the economy picks up and government borrowing is low (or even negative), the government should be cutting current spending or raising taxes (or both) to accelerate the fall in public debt.

This approach is, to an extent, 'fixing the roof when the sun is shining'. Yet this may make the task sound rather easy and carefree, when in fact this is far from the case. Rather, this approach imposes a stricter discipline on a government - forcing it to resist demands for spending increases during economic good times, not least so that it has money put aside to spend when times get tough again.

So the fiscal rules I propose are certainly not lax - quite the reverse. But they must also be flexible, and should be applied over a long timeframe. It is understandable that politicians think in five-year terms, but economic cycles cannot be expected to work in sync with electoral cycles. These fiscal rules are designed to be responsive to real-time upswings and downswings in the economy. The recent record of fiscal rules is, as I will show, not a happy one. But, sensibly framed and consistently applied, they could and should help to control the public finances and help to create the conditions for sustainable economic growth.

A short history of fiscal rules

Although earlier governments had general aims for fiscal policy - for example, to balance the budget - the Labour government elected in 1997 was the first in the UK to specify rules that would govern fiscal policy throughout its time in office. The reason for doing so was as much political as economic or financial. Before the 1997 election, the leadership of the Labour party felt they had to demonstrate that they could be trusted to manage the public finances. This was to be achieved in part by committing to the spending plans of the previous Conservative government. But this was only a short-term commitment: the plans only covered the first two years after the election. Fiscal rules were therefore deemed necessary to show Labour's commitment to managing the public finances in a prudent manner into the medium term.

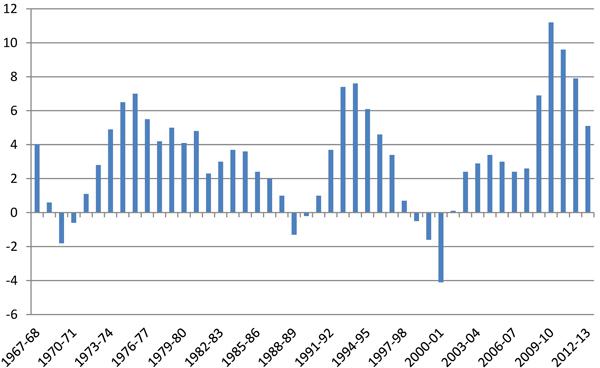

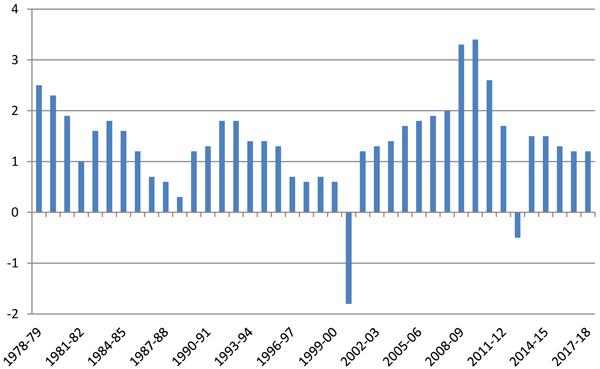

The depth of the recession that followed the financial crises of 2007 and 2008 forced Labour to abandon its fiscal rules, and for a short period policy operated without any rules or targets. But with net public sector borrowing reaching 11.2 per cent of GDP in 2009/10, the major political parties were obliged to offer alternative fiscal strategies at the 2010 general election, differentiated by the speeds at which each of them would reduce the deficit over the next five years. Although these were in effect alternative deficit targets rather than competing fiscal rules, the need for each party to be clear about what would guide its approach to fiscal policy was evident.

Figure 1: Public sector net borrowing (% of GDP)

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook - December 2012

The same will be required in the 2015 general election campaign. In fact, the existence of independent five-year projections of the main fiscal aggregates from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) will add to the pressure on parties to set out their fiscal plans. Any party not setting out a target or rule that will define its fiscal policy throughout the next parliament will face the accusation that it cannot be trusted with the public finances. Opinion polls show that the Labour party is still blamed for letting the deficit grow too large prior to, and in the aftermath of, the recession in 2008 and 2009. Whatever the truth of this perception, it means that Labour's leaders have to convince the electorate they would keep a firm grip on fiscal policy. Similarly, the Coalition parties, having failed to make as much progress as they hoped towards eliminating the deficit in this parliament, will need some sort of fiscal rule or target for the next one if they are to make the case that they can be trusted to finish the job they have started.

The failure of current fiscal rules

Fiscal rules now seem to be a necessity of modern political life in the UK, but they can become a debased currency if they are persistently missed, or if the goalposts are regularly moved. George Osborne claims the current rules demonstrate to bond investors that the Coalition government is serious about tackling Britain's 'deficit and debt problem'. In fact, they have turned out not to be fit for purpose.

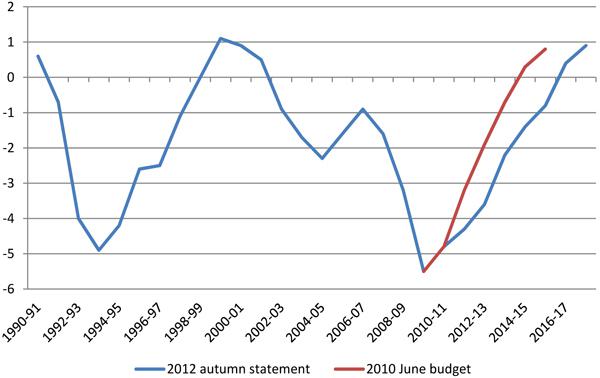

The first rule - to achieve a cyclically-adjusted current balance by the end of a rolling, five-year forecast period - is no real constraint at all. The chancellor only has to plan to eliminate the current deficit in five years' time; because of the rolling nature of the target there is nothing to compel him to actually deliver a current balance. The chancellor has already taken advantage of the leeway provided by this rule. His first budget in June 2010 envisaged a cyclically-adjusted surplus on the current balance of 0.3 per cent of GDP in 2014/15; by the time of the 2012 autumn statement, the first surplus was projected for 2016/17. Of course, given the weakness of the economic recovery, this relaxation of policy is not wholly a bad thing.

Figure 2: Cyclically-adjusted current balance (% of GDP)

Source: OBR, Economic and Fiscal Outlook - December 2012 and June 2010

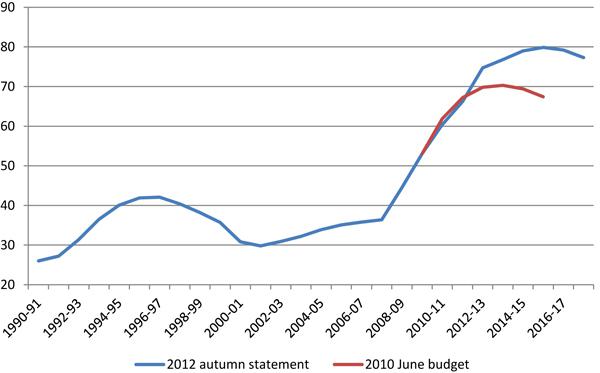

The second target - that public sector net debt should be falling as a percentage of GDP by 2015/16 - does specify a fixed date, but it too gives the chancellor enormous leeway. He can borrow as much as he likes in every year up to 2014/15, and as much as he likes in every year from 2016/17 onwards, and still meet this rule. In fact, the OBR now judges it unlikely that this target will be met: on current projections the debt ratio will not fall until 2016/17. This rule also proves not to be a real constraint.

Figure 3: Public sector net debt (% of GDP)

Source: OBR, Economic and Fiscal Outlook - December 2012 and June 2010

Clearly, new fiscal rules are needed for the next parliament, and not just because the current ones are flawed. In the next parliament's first year, if the current projections turn out to be accurate, the cyclically-adjusted current deficit will be just 0.8 per cent of GDP - it will no longer be credible to have a principal rule that seeks to eliminate such a small deficit over a period of five years. Moreover, the current debt target, which is for 2015/16, will by then be on the brink of obsolescence.

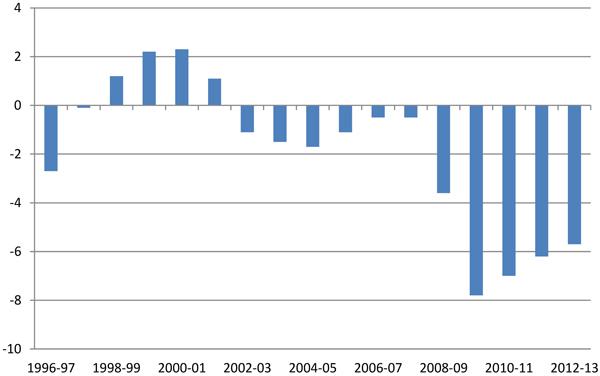

There will be no going back to Gordon Brown's rules: they too were flawed, though in different ways. His 'golden rule' restricted the government to borrowing only to invest over the economic cycle, with current spending having to be matched by revenues. While sensible in theory, the backward-looking nature of this rule meant that it was open to interpretation in ways that ultimately undermined its effectiveness. Changes to the assessment of when the economic cycle had begun, and when it might end, led to changes in the apparent scope to run deficits on the current balance in the remainder of the cycle.

Moreover, because the government delivered surpluses on its current balance in the early part of the economic cycle, it was able to run deficits towards the end of the cycle, even when the economy was clearly operating at, or above, full capacity. Even if the recession in 2008 and 2009 had been a 'normal' one, rather than the deepest since the 1930s, this would have limited the government's scope to respond. Meanwhile, Gordon Brown's supplementary rule - that public sector debt should remain less than 40 per cent of GDP - proved, like George Osborne's second rule, to be a constraint only until it became clear that it could not be achieved, at which point it was abandoned.

Figure 4: Public sector current balance (% of GDP)

Source: Source: OBR, Economic and Fiscal Outlook - December 2012

So, if the old rules are no good and new ideas are needed, what principles should guide those devising new rules for the next parliament?

New principles for new rules

Firstly, the OBR is here to stay. The UK is one of around a dozen OECD countries that have established a 'council' to evaluate fiscal policy. In most cases, as in the UK, these councils exist to complement fiscal rules and to monitor adherence to them, though in two instances (including the US) there is a council but no fiscal rule. In some cases the council has a wider remit to analyse policies in the areas of growth, employment and even climate change. The primary purpose of the Swedish Fiscal Policy Council, for example, is to impose discipline on the government when it sets fiscal policy, but in the past it has been heavily critical not just of the overall direction of policy but also of specific tax measures. Its remit extends to evaluating whether the economy is on track to deliver growth in line with its potential and full employment.

Second, the debt ratio will have to be cut. There is some evidence that extremely high levels of public debt are associated with greater economic volatility, though it is not conclusive. Better reasons for cutting debt are to create room for an easing of fiscal policy in any future severe downturn, and to reduce the growing burden on future generations that the current one is building up. Any new rules, therefore, should ensure that public debt is put on a downward trajectory, as a percentage of GDP, after 2015/16. This might mean reversing the fiscal priorities of the Labour and Coalition governments and making the debt ratio the primary aim of fiscal policy, even though this would make it more difficult for policy to respond to the economic cycle.

Third, capital spending should be excluded from the main fiscal target measure. However, this was the case with the 'golden rule', and is the case with the Coalition's main fiscal rule, and this did not stop Labour planning and the Coalition implementing swingeing cuts in capital spending when the time came to cut the deficit. Capital spending needs to be better protected, and there should be an explicit recognition that this means current spending has to be lower (or taxation higher) to ensure that debt is falling in relation to GDP.

Figure 5: Public sector net investment (% of GDP)

Source: OBR, Economic and Fiscal Outlook - December 2012

Fourth, the pace, timing and extent of fiscal austerity should be explicitly linked to growth in the economy. Attempting to manage fiscal policy without some awareness of where the economy is in the economic cycle is not a sensible approach. The Coalition's big mistake has been to plough ahead with tax increases and spending cuts irrespective of the state of the economy. Norman Lamont and Kenneth Clarke got this right in the 1990s: they waited until the economic recovery was secure before beginning to cut the deficit. The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has, de facto, made UK monetary policy contingent on economic recovery (and there is speculation that in the March 2013 budget this change will be formalised by the chancellor). The MPC's latest forecasts make it clear that policy will remain loose until the economy is growing at a reasonable pace, even if inflation is forecast to remain above its target rate for the next few years (the US Federal Reserve has made a similar commitment). Although this principle is less straightforward to follow for fiscal policy than it is for monetary policy, fiscal policy should also be contingent on growth.

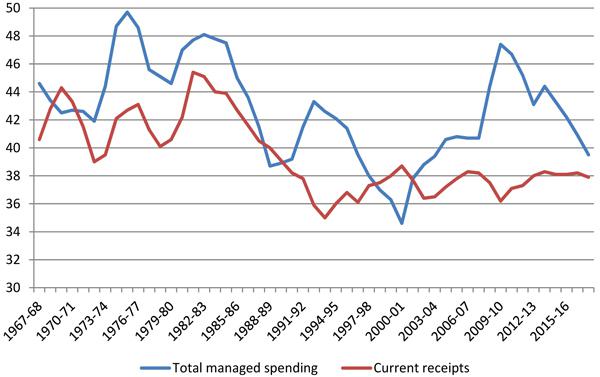

Fiscal rules are only part of the fiscal policy equation. They set the path for dealing with the deficit or with debt, but they still leave decisions to be made about the mix of spending and revenues that will be used to achieve the rules. It is already clear that these decisions are going to be very tough ones in the next parliament. The Coalition will produce a spending review for 2015/16 on 26 June, and it is not finding it easy to reach an agreement on what it should look like. The chancellor is facing resistance to further cuts in the departmental budgets of cabinet colleagues including Theresa May, Philip Hammond, Vince Cable and Eric Pickles; and the Liberal Democrats are resisting bigger cuts to the welfare bill. Meanwhile, the director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), Paul Johnson, has described the scale of the planned cuts in public spending beyond 2015/16 for unprotected departments as 'hard to contemplate'.

Figure 6: Public spending and receipts (% of GDP)

Source: Source: OBR, Economic and Fiscal Outlook - December 2012

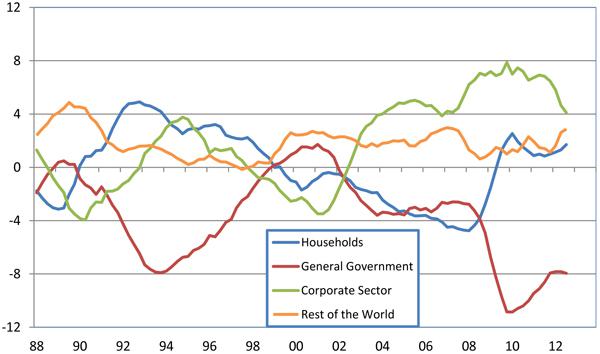

There is also the question of what is going on in the rest of the economy. If the government is borrowing, the rest of the economy must be saving, in aggregate. At present, the government's deficit is offset by surpluses in the household sector (as it seeks to reduce its debt) and the corporate sector, and by capital inflow from the rest of the world. Household deleveraging was expected, but the Coalition hoped that as it cut its deficit companies would be encouraged to invest much more, so reducing their surplus, and that exports would grow strongly, so reducing the rest of the world's capital inflow. However, investment and exports have not responded as expected, and the government's actions have therefore led to an increased ex ante desire to save and so to reduced demand and weakened growth.

Figure 7: UK financial balances by sector (% of GDP)

Source: Office for National Statistics, Quarterly National Accounts

Notes: Data is shown as four-quarter moving averages. Figures for the government and corporate sectors in Q2 2012 have been adjusted to exclude the effect of the transfer of Royal Mail pension plan assets.

Households are likely to be deleveraging for some time, so the government can only begin to cut its debt without further throttling the economy if the corporate sector saves less and invests more, and the rest of the world reduces its capital flow to the UK and buys more of our exports. This is the only way government deleveraging can take place while the economy grows at a healthy pace; it also allows the economy to rebalance away from consumption and towards investment and exports. However, it is unlikely that this will happen without support from government. Companies are naturally wary about increasing investment spending when the government is explicitly taking demand out of the economy and consumers are deleveraging. Policies to boost exports and to give businesses reasons to invest need to go hand in hand with debt reduction.

Fiscal rules after 2015

What exactly should a government elected in 2015 do? This will depend in part on the fiscal position that it inherits. At present, we have projections from the OBR out only to 2017/18. By the time of the 2015 budget, these projections will extend to 2019/20 and will give details covering the whole of the next parliament of one possible path for spending, revenues, debt and various measures of the deficit (though it is not clear how or whether the two parties of the Coalition, which might be gearing up to fight a general election with different fiscal plans, will agree what these numbers should be). Furthermore, the assessment of key factors such as the size of the output gap might well change between now and then, making it difficult to be precise now about detailed plans. However, given the importance of fiscal policy - both for the economy and for the outcome of the election - it is not too soon to start thinking about the rules that should guide it and, in broad terms, what the implications of these rules would be.

First, a new government might want to make specific, offsetting changes to the Coalition's tax and spending plans for 2015/16 - for example, to reintroduce the bankers' bonus tax and use the revenues for a jobs guarantee for long-term young unemployed people.

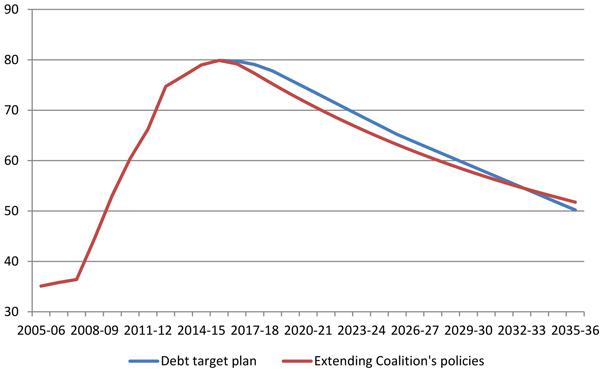

Second, it should set a target for the ratio of public debt to GDP in 2025/26. This should require a 15 percentage point reduction (on current projections, from 80 per cent of GDP in 2015/16 to 65 per cent in 2025/26). The rationale for setting a 10-year rather than five-year target would be to avoid the risk, during a period of economic weakness, of having either to abandon the target or to tighten policy in order to achieve it, thereby avoiding the trap George Osborne fell into with his five-year target. The target could be rolled forward by five years at the beginning of each parliament and lower debt could remain a principal aim of fiscal policy at least until the ratio reaches below 50 per cent. (This, it could be argued, is an arbitrary number, but there is no agreement on the optimal level of public debt - or even whether it is optimal for government to have any debt. It is, however, accepted that there is a strong case for slow adjustment to any target.)

It is difficult to compare this policy with the Coalition's current plans, because the latter only extend to 2017/18 (and any proper comparison would take account of the possible effects of different fiscal policy paths on economic growth and interest rates). If the actual current balance and net investment spending were left unchanged at their 2017/18 levels in the 2012 autumn statement projections (a deficit of 0.4 per cent on the current balance and net investment spending of 1.2 per cent of GDP), and assuming 5 per cent annual growth in nominal GDP, then by 2025/26 debt would have fallen to 63 per cent of GDP - two percentage points lower than the proposed target. To put this difference in context, the Coalition's June 2010 budget projected a debt ratio of 67.4 per cent in 2015/16; by the time of the 2012 autumn statement this had increased to 79.9 per cent.

Figure 8: Public sector net debt (% of GDP)

Source: OBR, Economic and Fiscal Outlook - December 2012 and IPPR calculations

Third, the government in 2015 should commit to lifting the ratio of public sector net investment to GDP to 2 per cent by 2019/20, and then to maintaining it at this level, on average, over five-year periods. The result would be net investment spending at a higher level than throughout the 1980-2007 period (see figure 5), delivering much-needed improvements to the UK's infrastructure. This will necessitate planning to have a larger surplus on the current budget than would be the case if investment spending was lower.

Fourth, it should reaffirm its commitment to the OBR as the chief arbiter of the government's chances of achieving its fiscal targets, and also as the body responsible for assessing the medium-term sustainability of fiscal policy. It should also extend the OBR's remit to allow it to make projections of the main fiscal aggregates under alternative economic scenarios. These could be delivered in the form of a report published several weeks ahead of the budget.

The government should set out spending and tax plans for the subsequent five years, based on its own economic forecasts and estimates of key variables such as the output gap. The OBR should then be asked to judge whether these are likely to place the government on course to meet its debt target and whether they are a sensible way to do so. If the government judged that a recession, or very weak growth, necessitated slower progress towards the target in the short term, the OBR would be required to validate or challenge that decision as it saw fit. Similarly, if the economy was growing strongly and the OBR thought the government should accelerate deficit reduction, it could say so. The OBR would, therefore, be the judge of whether the government was pursuing appropriate fiscal discipline. Giving this key role to the OBR would constrain government and ensure it was serious about reducing its debt.

Fifth, the government should plan to spread the remaining deficit reduction needed after 2015/16 to achieve its debt target evenly over the remaining four years of the next parliament. This would be in contrast to the Coalition's existing plans, which imply the front-loading of any remaining deficit reduction in the first half of the next parliament. It would mean borrowing more in the short term. If growth is still very weak at this time, consideration should be given to adopting a slower pace of deficit and debt reduction - possibly more than just allowing the automatic stabilisers to work - in 2016/17 and 2017/18. Alternatively, if growth is strong, deficit and debt reduction should be speeded up.

Sixth, the government should reassess the balance of the remaining deficit reduction that is to be achieved through spending cuts and tax increases. The Coalition's plans imply that almost all the deficit reduction that occurs in the next parliament would be the result of spending cuts. As the IFS says, this is 'hard to contemplate', if not implausible. Any party that promises to cut debt and not increase revenues will be deluding the electorate. The government could look, for example, to follow the 11 EU countries that are on track to introduce a financial transaction tax. The precise ratio between spending cuts and increased tax revenues would, however, depend on what is deemed plausible in 2015 and on how much more deficit reduction is needed.

Seventh, once the path for public spending is set out to 2020/21, the government in 2015 should hold a five-year spending review, covering the period from 2016/17 to 2020/21. This would give greater certainty to hospitals and schools over their budgets and make it easier for them to plan future expenditures. Any subsequent shifts in the overall stance of fiscal policy due to strength or weakness in the economy should be implemented through one-off measures. These might include additional infrastructure spending or a temporary tax cut when growth is weak, and cuts to welfare spending and a temporary increase in revenues (for example, by not indexing the personal tax allowance) when growth is strong.

Conclusion

This essay contains a lot of detail, much of it highly technical. That is as it should be. If we are to make fiscal rules work better in the future than they have up until now, they must be economically literate. Indeed, as we have seen, if they are primarily informed by ideological dogma, or swayed by political imperatives, they are not really fiscal rules at all.

That said, it is important to paint a picture of how something as technically arcane as a set of fiscal rules would have real impact on UK economic policy, and by extension the lives and livelihoods of British people.

Unless there is a change of approach on the part of the Coalition, it is likely that the UK economy in the years up to 2015 will remain stagnant. If that is the case, the fiscal rules outlined above would allow for more spending or lower taxes (or a combination of both) in the early part of the next parliament, thereby temporarily increasing the deficit. Yet this would not be seen as economically irresponsible by the markets or commentators, because the incoming government, with plans vetted by the independent OBR, would have committed itself in advance to reduce the ratio of public debt to GDP from 80 per cent to 65 per cent. The crucial point is that this would be achieved over a longer time frame of ten years, with the bulk of the work on debt reduction starting only when the economy is in a fit state to withstand further significant cuts in public spending and hikes in some taxes. Meanwhile, to ensure that vital infrastructure is not allowed to deteriorate, capital spending would be protected rather than being the first thing to be cut. If this fiscal policy is followed the UK would return to growth more quickly than would be the case if strict austerity were maintained, but thereafter there would not be a public spending spree or a slew of tax giveaways. Instead, spending priorities would have to be carefully chosen, because this would be the time to make substantial reductions in debt.

So this would certainly not be the fiscal equivalent of the obese person who continues to overeat today while promising to go on a diet tomorrow. The better analogy is with the person who sensibly allows themselves some hearty food in the winter because they know they will have to stick to salads when it gets warmer. And, to extend the metaphor, this has to be a better approach than the anorexia that is being imposed on the economy by the current fiscal rules.

The author is grateful to Andrew Adonis, Graeme Cooke, Tim Finch, Gavin Kelly, Nick Pearce and Simon Wren-Lewis for comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Related items

Bridge to the future: how to get the NHS through the winter and ready for reform

NHS staff across the country are gritting their teeth. Christmas parties have come and gone, but a more threatening annual tradition looms once again – the NHS ‘winter crisis’. This period, renowned for long waits and increased mortality,…

The great enabler: transport’s role in tackling environmental crises and delivering progressive change

In this special issue of IPPR Progressive Review we bring together leading political, academic and civil society thinkers to consider transport in modern Britain and its role in delivering a healthier, greener, more prosperous and…

The shape of devolution

How do we create transparent, fair and practical footprints for local power across England?