In Europe but not of Europe

Article

Political parties do not always have to be large to be influential. European parliament elections aside, the anti-European United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) remains a relatively small player on the British electoral scene. However, since winning a record 3 per cent of the vote at the last UK general election in 2010, the party's average standing in the polls has now climbed to around twice that figure. Indeed, in the low-turnout police commissioner elections in November this year it won as much as 11 per cent of the vote in the areas where it stood. In particular, much of this increase in support appears to have come at the expense of the Conservative party.

Unsurprisingly, Conservative MPs have taken fright at the prospect that votes lost to UKIP could mean vital parliamentary seats being captured by Labour. Many of them feel little love for the European Union anyway and have not needed much encouragement to demand that the EU budget is cut, to urge that Britain seizes the possible opportunity created by the eurozone crisis to negotiate a looser relationship, or to push for their party to shoot UKIP's fox by promising its own referendum on Britain's EU membership.

More surprising to some has been Labour's apparent willingness to fill its own sails with a Eurosceptic wind. It has voted in favour of a reduction in the EU budget and dropped hints that it too might be willing to back a referendum on Europe, once the fallout from the eurozone crisis has cleared. While Labour leader Ed Miliband made it clear in a recent speech to the CBI that Britain should remain part of the EU, he also argued that the institution was badly in need of reform and that, as a non-eurozone country, Britain was henceforth going to be a less integrated member of a more 'flexible' union.

In truth, Labour also appears to have good reason to be concerned about the electoral waves that the European issue can make. When, in December of last year, prime minister David Cameron symbolically 'vetoed' a EU treaty on fiscal coordination, the Tories temporarily wiped out Labour's lead in the polls. Neither party will wish to find itself relinquishing the prospect of power at Westminster because it had allowed itself to be outflanked on the issue of who was willing to stand up to Brussels.

But are our politicians correct in assuming that the voters themselves are in a particularly Eurosceptic mood? There are, after all, other possible explanations as to why UKIP's poll standing has grown. Previously, Conservative voters who were unhappy at how their party was performing in office could turn to the Liberal Democrats as a means of expressing their discontent. Now that Nick Clegg's party is in coalition with the Tories, that avenue no longer exists. For the disgruntled Tory, UKIP could well look like the only viable way of sending a message to HQ - in which case, perhaps, UKIP's rise has little to do with Euroscepticism at all.

One important characteristic of the British public is, however, clear. They have, in truth, never really taken Europe to heart. Very few feel a sense of European identity. Since 1996, when it began to track people's sense of national identity on a regular basis, the British Social Attitudes survey has typically found that just 12 per cent or so have claimed 'European' as one of the identities to which they adhere. Meanwhile, the European commission's own Eurobarometer survey has been asking people whether they feel British or European on an occasional basis since 1992: during that time never have more than 13 per cent of British respondents said they were wholly or primarily European - indeed, as many as 60 per cent have denied they are European at all.

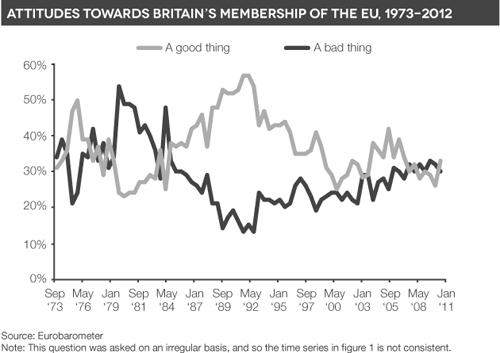

Figure 1

Against that backdrop, it is little wonder the argument that Brussels is 'meddling' in Britain's business seem to have popular resonance. Most people do not feel the kind of emotional empathy with Europe that might incline them to accept that Europe is indeed a legitimate locus of decision-making about what should happen here.

Even so, by the late 1980s - by which time Britain had been a member for some 15 years or so - it seemed that we had come to accept the instrumental merits of the European project. Labour and the trade union movement had dropped their hostility to Europe, seduced by the protectionist labour market legislation being promoted by then-president Jacques Delors. At the same time, it seemed our links with Europe were beginning to pay off economically, and while Margaret Thatcher increasingly sought to say 'No!' to Europe, John Major was embarking on a mission to take the pound into the European exchange rate mechanism, forerunner of the euro.

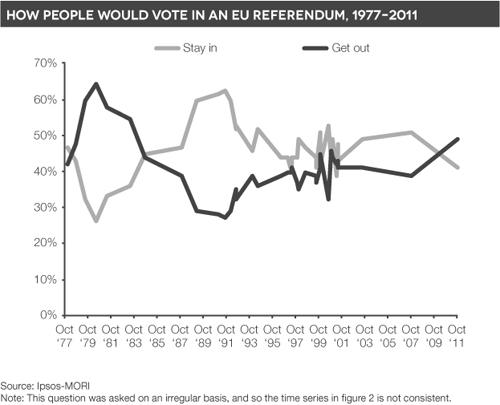

In the face of that elite consensus, the proportion who reckoned Britain's membership of the EU was a 'good thing' more or less doubled from little more than a quarter in the early 1980s to over half by the end of that decade (see figure 1). At the same time, MORI was consistently reporting that a clear majority of Brits would vote to stay within the EU, in sharp contrast to the position 10 years or so earlier (see figure 2). It seemed that Britain was finally comfortable with being part of Europe.

Figure 2

But then came 'Black Wednesday', Europe's ban on British beef following the discovery of 'mad cow' disease, and a rising tide of Euroscepticism inside the Conservative party. Lacking the stronger foundation that some form of widespread European identity might have provided, the pro-European mood of the general public did not long outlive the collapse of consensus support among the elite. By the turn of the century, the proportion saying that Britain's membership was a good thing was back down to a quarter, while support for staying in or getting out was evenly balanced.

So, in large measure, there is little that is new about today's Eurosceptic sentiment. In the absence of a consistently pro-European message from the country's main political parties, such an outlook seems to be the default position of much of the British public. Indeed, despite the eurozone crisis, the balance of opinion on whether Britain's membership is a good thing or not is no more adverse to the EU now than it was a decade ago, and is still markedly more favourable than it was during the early 1980s. To that extent, it is not clear that the public pressure on our politicians to take a tough line on Europe is really any greater now than it has been for most of the time that Britain has been a member.

In that case, then, might Labour be making a mistake in appearing to set a more Eurosceptic tone? After all, being more pro-European than their opponents did not prove a barrier to electoral success in 1997, 2001 or 2005 - throughout this period, the public was just as Eurosceptical as it is now. Does it really need to consider reassessing its stance now?

One concern Labour must have this time around is that, for the foreseeable future at least, the Conservative party might be able to remain united on the issue. In the 1990s, Europe was toxic for the Tories not because of their stance on the issue but because of their internal divisions. Now, by contrast, the pro-EU wing of the party is more or less mute. The Coalition government has been able to place a so-called 'referendum lock' on any further transfer of powers to the EU with hardly a murmur of protest. True, while some Tories simply want to loosen our ties with Europe, others really want to leave, and at the end of October the more determined Tory Eurosceptics helped to inflict a Commons defeat on their government in a vote on the EU budget. That is an experience the party will need to avoid repeating too often - but even so, for now at least, the debate within the Conservative party is about the staunchness of its stance, rather than the direction.

The European horse will not be an easy one for Cameron to ride. As Andrew Gamble has suggested, should the eurozone crisis be resolved and a closer and successful fiscal union forged between its members, then the Conservatives could well find themselves facing divergent and divisive pressures in terms of how Britain should respond. But in this parliament at least there will be few complaints on Cameron's benches if he continues to adopt a tough stance and, much like Harold Wilson in the 1970s, promises in the 2015 election that he proposes to renegotiate Britain's terms of membership.

Meanwhile, the argument that Britain's relationship with the EU should be reconsidered may now have a credibility that was lacking in the 1990s. Then, pro-Europeans could warn of the dangers of ending up in the slow lane of a 'two-speed Europe'. Now, thanks to the fact that Britain is not a eurozone member, the country is very firmly in the slow lane and, moreover, is very grateful to find itself there - according to a YouGov poll for Chatham House, no less than 60 per cent of the public never want Britain to join the single currency. So arguing for looser ties between London and Brussels appears more like an extension of the status quo and less like something that might be portrayed as a dangerous leap into the dark.

At the moment, of course, eurozone members have very little interest in worrying about Britain's particular concerns - they have the much bigger task of stabilising the single currency on their hands. But if and when that objective has been achieved - and thus, most likely, the eurozone members have installed a significant degree of fiscal coordination into their hitherto nationally determined public finances - the question of what the relationship should be between the EU and its non-eurozone members may well come to be regarded by the EU as a whole as a sensible one to ask.

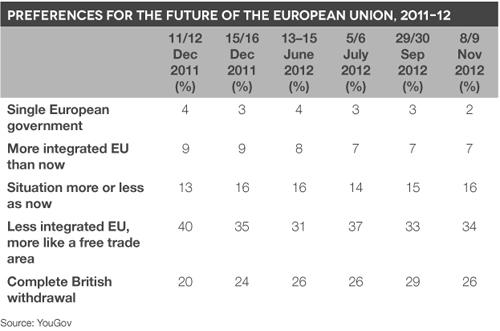

Meanwhile, the stance of 'staying in Europe but not too tightly bound by Brussels', which Miliband seems to want to adopt, may well prove to capture effectively the public mood. During the last 12 months, YouGov has invited respondents on a number of occasions to choose between five possible options for Britain's relationship with Europe, ranging from 'a fully integrated Europe with all decisions taken by a European government' to 'complete withdrawal from the European Union'. When presented with this set of options, as table 1 shows, no more than a quarter or so have said Britain should withdraw - even though, when a number of these very same polls asked people how they would vote in an EU referendum, between 36 and 48 per cent said they would vote to leave.

Table 1

The most popular option, supported by between one-third and two-fifths of respondents, is 'a less integrated EU than now, with the EU amounting to little more than a free trade area'. Evidently, many voters who say that currently they would vote to leave the EU could be persuaded that Britain should stay, so long as the ties with Europe were not too strong. After all, according to that YouGov poll for Chatham House, we rather like the fact that membership of the EU makes it easier to travel to, work in and even go to live on the continent - we would just prefer that not too many Europeans came here to live and work and that Brussels stopped making so many laws and regulations.

Indeed, the potential popularity of being 'in Europe but not ruled by Europe' may be the most important lesson to take away from Cameron's veto last year. According to YouGov, just a few weeks before the veto was wielded, only 31 per cent said they would vote in favour of staying in the EU, while as many as 52 per cent said they would vote against. Immediately after Cameron's veto, however, support for staying in rose to 41 per cent, balancing out exactly the 41 per cent who were opposed. If voters feel that Britain's interests are being promoted effectively within the framework of the EU then they are more likely to be willing to remain members of the club. In a country where few feel instinctively European, that is a reality that politicians on all sides need to recognise.

Related items

Women in Scotland: the gendered impact of care on financial stability and well-being

Women in Scotland are far likelier than men to take on childcare and other caring responsibilities, which puts them at an economic disadvantage.

Citizenship: A race to the bottom?

The ability to move from temporary immigration status to settlement, and ultimately to citizenship, is the cornerstone of a fair and functional immigration system.

Reflections on International Women's Day 2025

In a world that currently seems increasingly dominated by ‘strong man’ politics and macho posturing, this International Women’s Day it seems more important than ever to take stock of where we are on the representation of women in politics.