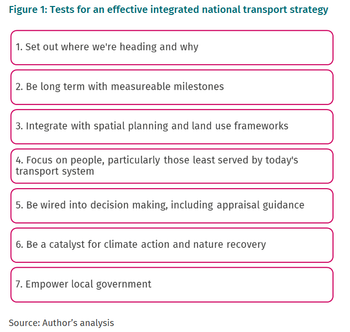

Joined up thinking: Seven tests for the integrated national transport strategy

Article

The UK government is producing England’s first integrated national transport strategy. In this blog, we set out IPPR’s seven tests to judge if the strategy seizes the opportunity to create a fairer, greener and healthier transport system that supports shared prosperity.

Transport isn’t working for people. It is also not living up to its potential in supporting the government’s missions. The Labour government inherited transport policies that failed to respond to the urgency of the climate and nature crises – showing a lack of leadership at home and risking the UK’s global reputation for environmental action. Meanwhile, the current strategic transport landscape is a fragmented mess of responsibilities and plans for different modes of transport.

In part to address these challenges, the government has now announced its vision for the new integrated national transport strategy. In the accompanying speech the former transport secretary, Louise Haigh, made a compelling case for why this matters for people across England. The new secretary of state, Heidi Alexander, oversaw a largely integrated transport system as deputy mayor of London, and she’s now in the position to deliver this for the rest of the country.

In this blog IPPR’s consider what it means for the government to be ‘joined up’ in its approach to transport. We outline seven tests that will determine whether the strategy addresses the challenges we’ve identified within transport and lives up to its potential.

Set out where we’re heading and why

The strategy must provide the missing vision for the future of transport in England, and the associated strategic goals to inform decision making. This should reflect the role transport plays in people’s lives, including its impact on the public realm through which people travel. This focus on people will require transport to be placed within the context of how people access the things that matter to them – these are partly driven by physical mobility but also intimately linked to spatial proximity and digital connectivity.

These long-term goals won’t be surprising. This strategy must aim to make the transport system sustainable and climate resilient, more inclusive and a tool for tackling inequality and social exclusion, better for our health and wellbeing, and a driver for local growth.

Be long term with measurable milestones

By 2050 the UK must have reached net zero, with all the changes to the transport system this requires. The transport strategy is a chance to describe what that future will look and feel like to people across the country.

However, a distant goal doesn’t always lead to the urgency of action required today. The strategy should set out clear near-term commitments for the coming five and 10 years. This can be complemented by annual delivery plans, applying the lessons learned from the previous government’s use of outcome delivery plans. Similar to the National Infrastructure Commission’s assessments, there should be a formal review of the strategy every five years, but there should be a mechanism for an annual refresh in line with DfT’s business planning cycle. Modal strategies and funding cycles should be aligned with these timeframes.

This strategy should contain high-level targets that allow its success to be measured and address:

- traffic reduction and mode shift

- emission reductions and air quality,

- accessibility and addressing the mobility gap for people with disabilities,

- people’s access to, and satisfaction with, public transport and active travel options,

- road danger.

Devolution is also an end in itself, not just a means for government delivery, so progress towards achieving greater sharing of funding, power and accountability across the country should also be assessed.

Integrated with spatial planning and land use frameworks

The future of transport cannot be separated from how we plan to use land in the future.

The government has committed to publish a land use framework for England. Given the numerous completing claims on how we use the land, a new approach is sorely needed. The new strategy must ensure transport infrastructure expansion is always weighed against the cost to nature and the opportunity cost of delivering other national priorities, such as housing, clean energy, food production and natural carbon sequestration.

The National Planning Policy Framework opens with a definition of sustainable development: “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. Planning decisions have historically not lived up to this commitment, locking people into expensive, unsustainable, car-dependent lifestyles. A new approach should see more housing built in areas with existing public transport and active travel options, with investment used to improve these networks, and embrace transit orientated development, where public transport infrastructure is placed at the heart of plans for new neighbourhoods.

Focus on people, particularly those least served by today’s transport system

For too long it has felt like decisions about transport have been made based on assumptions about inevitable traffic growth and the value of a small group of people’s time. These ideas are baked into possibly the most complex transport appraisal system in the world: the DfT’s Transport Appraisal Guidance. Used properly, this guidance provides decision makers with confidence on achieving good value for money and a sense of the real-world impacts of investment. Too often it is used to justify pre-made decisions about the need for a specific approach without appropriate thought given to alternative options, long term strategic fit or what would make the most difference to local communities.

This strategy is an opportunity to ask, “what do people really want from the transport system?”. The voices of those most frequently excluded from decision making, and who have been most negatively impacted by the poor decisions of the past, should be central to answering this. The government should invest in new ways for transport decision makers to listen and respond to the public, including through regular citizens’ juries provided with the power to steer and decide government policy.

Be wired into decision making, including appraisal guidance

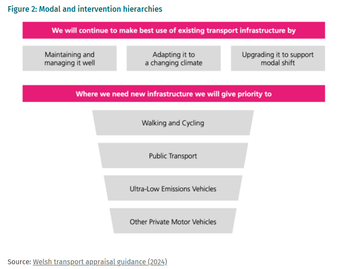

England can take significant inspiration from Wales in its approach to transforming decision making. The Welsh government has established a clear set of goals and made these central to how its own appraisal guidance, WelTAG, works. At the heart of this is an unambiguous intervention hierarchy that defines both how existing assets will be used and the priority for the future (see figure 2).

DfT has developed seven scenarios for the future of traffic growth in the UK, referred to as the common analytical scenarios. None of these set out what would be considered a desirable future. With the development of this strategy, a new scenario that reflects the government’s goals should be added.

Be a catalyst for climate action and nature recovery

There is no more existential threat to global security and the quality of life of people in the UK than the climate and nature crises.

Given the significance that Labour have placed on reclaiming global leadership on the environment, and transport’s status as our most emitting sector, their approach to ‘fixing’ transport must reflect the urgency of these issues. The new strategy must therefore be aligned with a lawful, fair and evidence-based Net Zero Strategy, one that establishes sectoral carbon budgets, and a refreshed Environmental Improvement Plan.

Empower local government

Andy Burnham, Mayor of Greater Manchester, is right to say: “the main policy that needs to be baked into the mindset of transport at every level is devolution by default.”

Recognising that local and regional government has different capabilities and capacity for transport planning, the UK government should identify where it can help build this expertise and foster collaboration between authorities. The central enabler for many areas of the country will be the provision of sufficient, long-term, integrated funding and ability to raise and retain more funds locally.

Conclusion

The ambition of the integrated national transport strategy is as welcome as it is necessary.

The former transport secretary started the work of building firmer foundations for transport and ensuring investment was going to where it would make the most difference during this parliamentary term. She threw out some poor value road schemes and provided a funding settlement for buses that has been fairly shared across the country.

This strategy, and the comprehensive spending review, provides the opportunity for the new secretary of state to build on these decisions and put the country on the path to a fairer, greener and healthier transport system. These changes will also ensure transport is playing its role in improving living standards and fostering shared prosperity.

Responsibility for success cannot rest with the DfT alone. This must be a cross-government endeavour with the Treasury as the key partner. Not only will the chancellor provide the investment required to deliver it, she will also need to implement supportive fiscal policies – including taxes that support the shift to more sustainable travel behaviours and greater devolution of funding and powers to local areas.

The government are right to put ‘people first’ and prioritise the needs of those held back by lack of access to good transport options. This approach will attract its critics, but they are the minority. Unlike the previous government, Labour must stand beside local leaders delivering transport schemes that will provide meaningful improvements in people’s lives.