Making work pay: The government's mandate on worker's rights

Article

The new Labour government has promised to improve the rights of working people.

Labour’s manifesto pledged to strengthen employees’ protections at work, establish a ‘Fair Work Agency’ to better enforce workers’ rights, and remove restrictions on trade union organising. Since the election they have announced an Employment Rights Bill, established a Cabinet Committee on the Future of Work and started to roll back the previous government’s anti-union legislation.

There is a good economic case for strengthening workers’ rights. The UK is stuck in a low-pay, low-productivity and low-investment rut which is damaging the living standards of working people. Boosting the pay of the lowest earners, tackling labour market insecurity and improving opportunities for workers to join unions will help to lay the foundations of broader economic prosperity.

It’s also politically vital that the government delivers on their manifesto commitments. Polling shows that stronger workers’ rights are widely supported by people who voted for Labour in July. Tackling low-paid, precarious employment could help the government to consolidate and expand its voter base, given that every constituency in the UK has a majority of people who believe workers’ rights should be strengthened. The flip side of this is that failing to ‘make work pay’ would likely damage Labour’s prospects at the next election.

Making work pay strengthens economic security for millions

Working life is plagued by insecurity for many people. 6.8 million workers, more than 1 in 5 of everyone in employment, are in insecure work (i). Since 2011, the number of insecure jobs has increased nearly three times faster than secure forms of employment. Insecure work compounds the problem of low pay: the lowest paid workers are most affected by contract insecurity, volatility in pay or hours and underemployment. Workers who are younger or from minority ethnic backgrounds are more likely to be in insecure work.

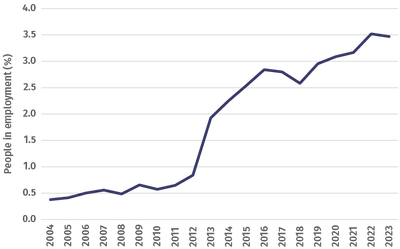

The growth of insecure work has been largely driven by increases in the reported use of zero-hours contracts. The number of people who report being employed on zero-hours contracts has increased tenfold in the last two decades, while most other types of insecure work have declined in recent years.

Figure 1 (ii): The reported use of zero-hours contracts has exploded in the last two decades

Percentage of people in employment on a zero-hours contract (%)

Source: ONS 2024

Tackling insecure work through stronger employment rights and raising the pay of low-income workers will build greater economic security for millions. Banning exploitative zero-hours contracts, ending the practice of ‘fire and rehire’ and making protection from unfair dismissal a right from the first day of employment, alongside parental leave and sick pay, will help to address labour market insecurity.

The government also plans to raise the pay of low-income workers. The Low Pay Commission has been instructed to factor living costs into the minimum wage level to introduce a genuine living wage. The proposal to establish a Fair Pay Agreement for adult social care workers also has the potential to raise minimum pay and conditions for workers in a sector that is plagued by low pay. If the agreement is successful it could prove a useful model for other sectors with high rates of low pay and weak levels of unionisation.

Better enforcement ensures workers can access their new rights

Strengthening workers’ rights and raising the pay of low-income workers must be supplemented by stronger enforcement to ensure that workers are able to enjoy their new rights. Many employers do not comply with legal workplace requirements, meaning that almost one-third of workers who should receive the minimum wage are underpaid.

The state’s ability to clamp down on bad employers is unhelpfully fragmented. Responsibility for tackling non-compliance is currently split across six different state authorities, each with different remits (iii). This undermines enforcement and leaves workers vulnerable to exploitation, including modern slavery. The government’s pledge to strengthen enforcement by establishing a new Fair Work Agency is therefore a welcome move. Three existing labour market enforcement bodies will be amalgamated into the agency, which will have the power to levy fines, inspect workplaces, lodge civil proceedings and bring forward prosecutions.

Strengthening workers’ rights and raising the pay of low-income workers must be supplemented by stronger enforcement.

The Fair Work Agency’s ability to enforce new workers’ rights will be determined by its resourcing and its interaction with other government departments. The agency needs to be properly funded: the International Labour Organisation recommends that there should be at least one labour market inspector per 10,000 workers, but the UK only has 0.29 per 10,000 workers. The introduction of new rights for workers is likely to result in higher demand for employment tribunals, which will require additional investment if they need to process additional claims. Experts also advise that the Agency should be operationally independent from Home Office powers and governance to ensure that migrant workers are able to access employment justice.

Stronger unions can lay the foundations for widespread prosperity

Trade unions exist to aggregate the bargaining power of working people, enabling them to improve their pay and the quality of their work, but the decline of union density and collective bargaining has contributed to an imbalance of power at work. Improving the ability of unions to organise in workplaces can reverse this trend.

Declining trade union membership from the late 1970s coincided with a large drop in the share of national income going to workers. Even after the ‘labour share’ recovered in the 1990s, rising inequality suggests that this growth has not been shared fairly. Trade union membership and recognition are associated with higher quality work and greater protections for workers from exploitation, and the decline of unions in recent decades has contributed to the growth of badly paid and precarious employment.

Trade union membership and recognition are associated with higher quality work and greater protections for workers from exploitation.

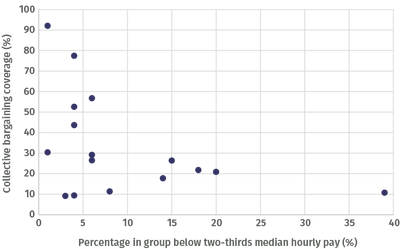

Making it easier for trade unions to sign collective agreements with employers will help to tackle low pay. Evidence shows that sectors with higher incidences of low pay often have lower collective bargaining coverage.

Figure 2: Sectors with higher collective bargaining coverage generally have less employees on low pay

Collective bargaining coverage (%) and proportion of employees on low pay (% earning below two-thirds median hourly pay) by industry (2022)

Source: Resolution Foundation 2024 and DBT 2023

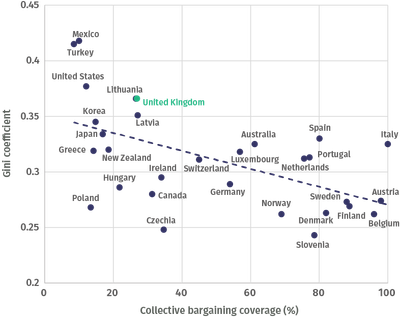

The changes will also lay the foundations for more broad-based economic prosperity, given that countries with higher collective bargaining coverage are generally less unequal.

Figure 3: Higher levels of collective bargaining are associated with lower inequality for OECD countries

Gini coefficient and collective bargaining coverage (%), latest pairing available

Source: OECD 2024 and OECD 2024

The government is planning to remove barriers to trade union organising by simplifying the process of statutory recognition and ensuring workers have a reasonable right to access a union. These changes will start to strengthen the role of unions in workplaces and the labour market.

There are political rewards for making work pay

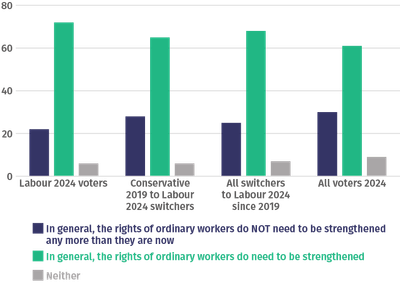

The government will benefit politically from strengthening the rights of working people. Polling conducted by IPPR and Persuasion UK shows that stronger workers’ rights are widely supported by people who voted for Labour in the election. Among Labour voters, 72 per cent support policies which strengthen the rights of ordinary workers, including almost two-thirds (65 per cent) of Conservative to Labour switchers.

Figure 4: Voters overwhelmingly back the need to strengthen workers’ rights

Source: IPPR 2024

Tackling low-paid, precarious employment could also help the government to consolidate and expand its voter base ahead of the next election. More than twice the number of people support stronger workers’ rights than don’t across the country, and every constituency in the UK has a majority or plurality of people who believe workers’ rights should be strengthened.

This should give the government confidence in strengthening workers’ rights in the face of a small but vocal minority who are criticising its policies in the media. As we move into the crucial phase of implementing the Employment Rights Bill, it should also serve as a reminder that failing to ‘make work pay’ would likely damage Labour’s prospects at the next general election.

Ensuring this government delivers a ‘new deal’ for working people

Stronger regulation and enforcement will start to tackle low-paid, insecure work but will not be enough on its own. To deliver a truly ‘new deal’ for working people this government must improve the bargaining power of workers, especially those on low pay and insecure contracts. Supporting unions to expand their membership and sign new collective agreements will help to achieve this, but the government will also need to use the tools of the state to strengthen workers’ wider ability to bargain for better pay and conditions. IPPR’s new programme of work on ‘rebalancing power to workers’ will explore how the government can deliver a genuinely ‘new deal’ for working people and shift the UK’s economic model to one characterised by higher pay, higher productivity and higher investment.

Notes

(i) There are different definitions of ‘insecure work’. We follow the Work Foundation’s definition, which includes workers that are on fixed-term contracts.

(ii) Data relates to the last quarter in each year.

(iii) The bodies are: HMRC National Minimum Wage non-compliance (HMRC NMW); Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA); Employment Agency Standards Inspectorate (EAS); The Pensions Regulator (TPR); Health and Safety Executive (HSE); & Equalities and Human Rights Commission (EHRC). Source: https://www.resolutionfoundati....