On the side of motorists

Article

Cars are central to many people’s lives and the 2021 Census revealed that this dependency has grown over the last decade. Communities across the UK understand the environmental and social necessity to change this, and want to see action to provide people with cheaper, greener and healthier transport options. Politicians must avoid the easy headline and be ready for a grown-up conversation about the challenge, necessity and benefit of changing how people travel.

I just want to make sure people know that I’m on their side in supporting them to use their cars

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, 30th July 2023

Politicians says they are on the ‘side of motorists’. This will be a statement we hear repeated ad nauseum in the build-up to the next general election. The signs were there before the Uxbridge by-election with an MP claiming that 15 minute cities were socialist conspiracies and ministerial criticism of ‘unpopular’ low traffic neighbourhoods. But the central role that the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) is seen to have played in keeping a seat that has not voted Labour for over fifty years in Conservative hands has, for some, demonstrated that transport policies might be able to be exploited for votes.

Cars are integral to the lives of many, but the impacts of this dependency are not fairly shared

Cars are an increasingly ubiquitous part of modern Britain, with 12 cars for every 10 households in England and Wales (ONS 2023). More than three quarters of households in England and Wales own a car, with the number of households with access to a car increasing by 4 per cent between the 2011 and 2021 Census, and over a million more households now owning multiple cars (ibid). Being ‘on the side of motorists’ feels therefore to be a reasonable starting point for any politician hoping to get elected, but shows a failure to engage more deeply with the inequality that underpins this large-scale car dependency.

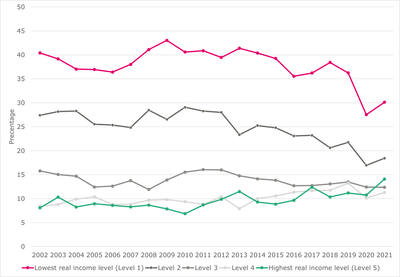

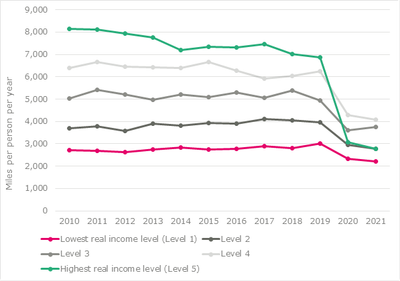

The headline statistics on car ownership hides the details on who is most likely to own and use cars. Those on the lowest income are still more than twice as likely to have no access to a car than those in the wealthiest households, despite an increase in car ownership among poorer households prompted by the pandemic (see figure 1). In 2019, the wealthiest travelled more than twice as far by car than households on the lowest incomes (see figure 2). In 2021 those on the lowest incomes were still driving less than all other income groups, even though they lack the flexibility that wealthier households have used to change how and where they work as a result of the pandemic.

FIGURE 1: THOSE ON THE LOWEST INCOMES HAVE BY FAR THE LOWEST ACCESS TO CARS

Source: Author’s analysis of Table NTS0703: Household car availability by household income quintile: England, from 2002 (DfT 2023)

FIGURE 2: THOSE ON THE LOWEST INCOMES TRAVEL THE LEAST BY CAR

Source: Author’s analysis of Table NTS0705: Travel by household income quintile and main mode / stage mode: England (DfT 2023)

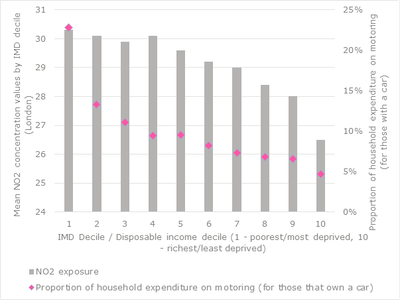

Those on the lowest income are hit two-fold by the impacts of such widespread car dependency – both in their wallets and in their lungs. For those living on the very lowest incomes, the running costs of keeping a car can exceed a fifth of their weekly income and it is those living in the most deprived communities that have the highest exposure to air pollution (see figure 3). Although air pollution affects everyone, it is known that exposure to it has the worst health impacts for those on low incomes. This reveals some of the limits of the ‘pro-motorist’ message – by failing to address car dependency in the UK we fail to acknowledge the inequality it exacerbates: in who has access to cars and benefits from existing car-centric urban planning, in the costs that forced car ownership places on those living on low incomes and in the health impacts from car traffic that fall disproportionately on low income households and communities.

FIGURE 3: THOSE LIVING IN THE MOST DEPRIVED COMMUNITIES HAVE THE HIGHEST EXPOSURE TO AIR POLLUTION AND LOW-INCOME DRIVERS SPEND THE HIGHEST PROPORTION OF THEIR INCOME ON MOTORING

Source: Author’s analysis of Williamson et al 2021 and the Living Cost and Food Survey (ONS). Note that the mean proportion of household spending by the top income decile will be lower than presented here due to the impact of income capping within the data.

Freedom to do what you want and need to do, when you want to do it

Those who talk to the public regularly about car use will hear one thing time and time again: that driving gives them freedom. Using a car means they can reliably get to where they want to go in the shortest amount of time, and have the ability to change plans, do some shopping, pick up the kids, avoid the rain, get out for a walk in nature and drive right back to their door, at whatever time of the night and day they choose. Most don’t believe that there is any other way of meeting these needs. Given the car dependency baked in to many housing developments, regional inequality in access to public transport and the perception that cycling is too dangerous, in parts of the UK many will be right.

The public recognise this lack of choice is unfair and support action to change how people travel. They want to see people given the meaningful opportunity to leave their cars at home and travel more sustainably (and cheaply). Seven in ten (71%) people support action to encourage more people to walk or cycle instead of driving a car. The majority of people in UK cities want to see more government spending on walking or wheeling, cycling and public transport than on driving. The freedom that people associate with driving masks the reality that many don’t have a choice.

IPPR’s deliberative research with the public has shown that in places as diverse as the South Wales Valleys and Anglesey, Liverpool, Glasgow and Thurrock there is an appetite for a different approach to transport. Whilst recognising the need that cars meet for many, they have been quick to describe the negative impacts of this too – the congestion, air pollution, noise, the space they take up, the numbers of people killed and injured on the roads and the role they play in the climate and nature crises. They told us that with the right leadership the UK can break our dependency on cars and deliver huge benefits for individuals, communities, and the environment.

Politicians need to be honest about the future of travel

Much may change between now and the next general election, but one thing is sadly certain – transport will still be the largest driver of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions and we will still lack a credible UK-wide plan to address this. The rowing back of what ambition there was to tackle transport emissions in the revised net zero strategy puts the UK’s climate commitments in doubt. The disingenuous and polarising way in which policies aimed at addressing this central net zero challenge are being framed should concern us all. The extreme weather events playing out in headlines across the globe comes just a few months after the IPPC’s warning of the rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable future.

Political leadership means recognising the challenges we face and engaging the public in an honest conversation, not offering false reassurances and seeking to further delay meaningful action. No one is arguing for a future without cars. There is not a forecast for travel in 2050 that doesn’t see cars remaining as a key part of our lives. But that doesn’t mean we should pretend that ever-increasing levels of car ownership and traffic is desirable for anyone, especially not those on the lowest incomes.

The UK deserves a real debate about what we want the future of transport to look like. The next government must deliver a strategy for changing how we travel that keeps the UK on track to meet our climate commitments and seizes the opportunity to deliver a transport system that is fairer, healthier and allows future generations to thrive. Achieving that will put them on the side of motorists, on the side of those on the lowest incomes and on the right side of history.