Scotland’s new climate legislation risks repeating mistakes of the past

Article

A bold alternative is needed that asks decision makers to be explicit about the changes they will support, not just a headline target figure

Earlier this year, the Scottish government declared its 2030 climate target to be out of reach. What had been a “legally binding” target turned out not to be so binding after all. New legislation is currently being rushed through the parliament to allow for changing the targets. That legislation carries a real risk of replacing one ineffective approach to climate policy with another.

The bill proposes a framework that roughly follows these steps:

- the Climate Change Committee (CCC) advises what level the targets should be,

- government proposes targets to parliament,

- parliament adopts the targets,

- government writes a plan for how to deliver the target,

- government and parliament put in place policies and legislation to deliver the target

Call this “the target-first model”. It is inspired by the way the UK government sets climate budgets. That, in itself, should serve as a warning it may be ineffective: under the target-first model, only a third of what is needed for the UK’s 2030 budget is covered by credible plans.

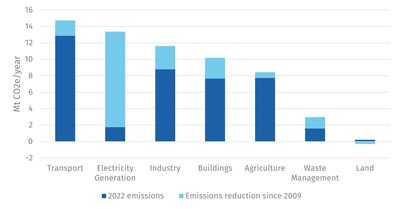

Why is this and will the same failures happen in Scotland? The key to understanding the problem is the difference between past emissions reductions, and what comes next. The closure of fossil-fuelled power stations, made possible by impressive deployment of renewables, has taken the biggest chunk out of our emissions. But that’s a cut that can’t be repeated. Now we need to bring emissions down across the rest of Scotland’s economy and society, and that means different kinds of change to what’s gone before. These sectors are complex to decarbonise, requiring all sorts of coordinated change. They reach right into daily life: where and how we travel, how we heat our homes, the food we eat. They need upfront investment and can have significant distributional impacts.

Figure 1. Emissions reductions since the Climate Change (Scotland) 2009 Act have been deep in the electricity sector, but shallow across other sectors

Source: Analysis of Scottish government (2024) greenhouse gas statistics.

The problem with the target-first model is that it separates target setting from consideration of how these different sectors will change. At the beginning of the process, analysts, mainly at the CCC, explore scenarios they believe to be plausible and work out future emissions levels these scenarios imply. Through this process, a great many consequential choices and assumptions about the pace and scale of change get packaged up into a black box of inscrutable emissions figures. Ensconced in this black box, these choices pass through the middle of the process – parliament adopting the targets – with too little debate.

However, after the targets have been set, the black box has to be reopened for plans and policies formulated. At this point politicians can be surprised by the kinds of change needed. They find themselves unwilling to do what the CCC assumed they would at the beginning of the process.

The focus on greenhouse gasses rather than concrete change only encourages this. Our emissions are fifty per cent below their 1990 levels, so politicians can easily slip into the false sense of security that we’re “half way there”. This ignores the fact that a huge chunk of future decarbonisation – across transport, heat and industry – will rely on electrification. That means change in those sectors on top of continued growth in clean power. The target-first model doesn’t force decision makers to think through the realities of change.

This is not a criticism of the CCC and its work, but of the target-first model as the process of setting targets and developing policy. The CCC does not hide its assumptions, hoping to smuggle them past witless politicians. Quite the contrary, the committee is scrupulous in its transparency, providing an amazing service in making a huge mass of data, analysis and evidence freely available. But it is not a democratic decision-making body. While the CCC can build a variety of models of the future, it is decision makers who need to own that vision. The problem with the target-first model is that it doesn’t require decision-makers to take that ownership and commit to the changes it implies.

A different approach is needed, one in which decision makers explicitly consider the concrete changes they are willing to commit to. Instead of separating the setting of emissions targets from the creation of plans, as the target-first model does, these need to be considered together. Such a process would combine setting the climate targets with writing a climate change plan. It would require decision makers to think through their responsibilities both to the climate and to the impacts of change in Scotland

Here's an outline for how such a “combined model” could work:

- The CCC, the civil service and the wide range of climate stakeholders together construct a menu of options for decision makers to consider. These focus primarily on material changes that would take Scotland towards net zero, like the speed with which we replace boilers with clean heat, or the number of sheep and cows we grow and eat.

- These options are backed up with a set of policy proposals that would credibly deliver those material changes, quantifying emissions, costs, distributional impacts and other issues.

- Alongside this, the CCC analyses the relationship between Scotland’s emissions and the global effort to tackle climate change. This could take the form of emissions “envelopes” that reflect different ways of understanding how Scotland’s emissions relate to the rest of the world (e.g. different global temperature change limits.)

- Parliamentarians use these resources to formulate a climate package, setting out the real-world changes are they willing to commit Scotland to. In deliberating the contents of the package, decision makers would weigh up the need for Scotland to make a meaningful contribution to the effort to tackle climate change, with the policies they can commit to supporting.

This approach front-loads planning and policy making compared with the target-first model. As such, it would likely be messier and slower to reach a climate target. But the point is to arrive at a robust climate programme. If decision makers cannot commit to a particular change that would be needed to deliver a target, it is better they make that position clear in the targets they endorse, and stand accountable for their choices.

An ambitious target is important, but sectoral pathways are critical

Drawing decision makers into the creation of sectoral plans would result in the creation of a more robust set of sectoral pathways than those the Scottish government has managed so far. Robust sectoral pathways are critical because of the coordination needed to tackle our remaining emissions. We can’t get to mass deployment of heat pumps without upgrading the electricity networks running down our streets. Switching to EVs, public transport and active travel can’t happen unless we put the right infrastructure and services in place and redesign how and where we live, work and play. Shifting meat and dairy out of our diets won’t make a difference if we keep growing sheep and cows to export their products, but by the same token, cutting livestock numbers is counterproductive if we just import climate-harming food to satisfy our unchanged diets. If we’re expecting young people to train up for a job in the low carbon transition, they need to know the skills they’re developing are actually going to land them a job.

Robust sectoral pathways are essential to coordinate action. If they are vague (or just absent) actions and investment just moves too slowly as the risk the rest of the system doesn’t come with you is just too great. This is increasingly recognised in the electricity system and has led to various reforms, including the creation and nationalisation of a new National Energy System Operator whose plans will support coordinated investment in networks and renewables.

The same principles apply across buildings, transport, industry, agriculture and land use. Government has a critical role to play in unlocking investment and activity by making commitments to see change happen in particular ways. The combined model of setting climate targets and plans together will deliver this.

A counter argument might be that committing to sectoral plans ties government’s hands, leaving it unable to react to innovative new technologies. That argument might have held water a decade ago, but we’ve effectively run out of time given the scale and complexity of the coordinated changes we need to achieve. A robust approach to net zero would stop waiting and pick up the pace with technologies we have today. Course-correcting a pathway to net zero because a new technology is available is much less of a problem than leaving decarbonisation until it is too late.

Why doesn’t the target-first model work?

Understanding how did the 2030 target ended up being out of reach helps illustrate the problem with the target-first model. While that target was set against the advice of the CCC, the structure of the process was similar. Crucially, the adoption of the target in parliament was not the result of decision makers thinking through the real-world changes they would be willing to stand behind.

The 75 per cent target was a reaction to growing evidence that time was running out to deliver the Paris target of limiting temperature rises to 1.5 degrees. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) had concluded in 2018 that 1.5 degrees was still possible, but would require “deep emissions reductions”. Analysis of Scotland’s “fair share” of the global remaining emissions budget argued for an 80 per cent target for 2030. Parliamentarians went for 75 per cent, a compromise between 80 and the Scottish government’s initial proposal (a 66 per cent).

Strikingly absent from the process of setting the target was analysis of what meeting the 2030 target would mean for Scotland (even though the IPCC report had been explicit that “rapid far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” would be needed). The target-first process deferred meaningful discussion of these changes until after the targets were set.

The government published a Climate Change Plan update at the end of 2020, which started to spell out a vision of what hitting the target would mean. The plan was broad, but some eye-catching commitments for 2030 included cutting 20 per cent off the amount we travel by car, and switching boilers for clean heat in all homes using oil and over a million homes using gas (more than half the total). Very little, if any, progress has been made toward these goals, and indeed the clean heat 2030 target has been dropped.

At issue here is not whether these changes could be achieved in practice, but that these changes would need a strong political consensus for a government to confidently enact the bold policies and legislation they would require. These sector specific targets were not the product of political deliberation, but the output of spreadsheets constructed by civil servants and their consultants. As such there was little political appetite to follow through and develop the major change programmes the targets would have required.

As a side note here, it is true that over this period government and politics was somewhat distracted by the little matter of a global pandemic. Of course, the pandemic would have slowed a government committed to the material changes needed to hit the 75 per cent target. Such a government might have concluded that more time was needed and that it would now see clean heat in over a million homes by, say, 2032 rather than 2030. But instead, at the end of last year it simply abandoned the target altogether. The pandemic certainly challenged the government’s climate change programme, but the fundamental issue was the split between the political commitment to the abstract emissions target and the absent political commitment to the changes needed to deliver it.

Why do we need world-leading climate policy in Scotland anyway?

At the time it was set, Scotland’s 2030 target was lauded as world-leading. That leadership is important because, in many respects, it is the point of Scotland having climate targets in the first place. Climate is a collective problem: we need emissions to come down rapidly across the whole planet, not just in Scotland. But how can our community of five and a half million souls expect the rest of the world to take urgent action, if we are not willing to deal with our own emissions at a pace that matches the environmental crisis. An ambitious climate programme has two functions here – showing the rest of the world we will play our part and not free-ride on others’ efforts, and setting a template for how other societies can successfully transition.

Having been knocked off course, climate policy in Scotland needs to rebuild credibility to make our contribution globally meaningful. That means more than setting a headline climate target. It means setting clear plans for how Scotland will change to become a net zero society. The combined process outlined above shows how this can be done.

What choices do decision makers need to grapple with?

There are multiple plausible pathways to net zero, with different approaches to decarbonisation within sectors, different balances emissions across sectors, and differences in the pace of change.

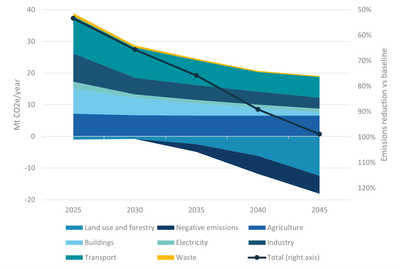

Take, as an example, analysis of existing climate plans commissioned by Scottish government at the beginning of this year (Figure 2). The first striking detail of this pathway is how much it leans on the “net” part of “net zero”. Under this pathway, positive emissions falling to around 20 Mt CO2e/year by 2045 (which is, coincidentally, about 75 per cent below their 1990 baseline level). Negative emissions come from land use, forestry and negative emissions technologies (power stations fuelled with biomass and fitted with carbon capture).

Figure 2: One potential pathway to net zero by 2045 would split effort between decarbonisation and negative emissions

Source: Analysis of Ricardo (2024) modelling for Scottish government (phase 2 central scenario).

Here are some issues decision makers would need to address when considering a plan and target together through the combined process:

- Should Scotland’s emissions pathway rely so heavily on land, forestry and negative emissions technologies? Are decision makers comfortable with the risks this implies, particularly as this part of the analysis has the health warning it is “high uncertainty” and depends on imported biomass? What contingencies are they willing to consider to manage these uncertainties?

- What should the relationship be between Scotland’s emissions pathway and the rest of the UK’s? In broad terms, Scotland represents about a third of the UK landmass and a twelfth of the population. The pathway in figure 2 implies positive emissions at roughly 3.5 tonnes per person in Scotland. Less land per person in other UK countries implies less potential for negative emissions. That means net zero would require lower per person positive emissions than in Scotland. Is that fair? Should these negative emissions be funded through the Scottish budget or shared with UK government, in light of the pressure this sector is anticipated to place on Scottish fiscal sustainability?

- In the example pathway in figure 2, around half the reduction in positive emissions on this pathway happen between now and 2030. Would decision makers be willing and able to enact policies that achieve this pace of change? For example, are they willing in principal to support the kind of regulations proposed for heat in buildings and bring them in at the pace assumed by analysts?

- In figure 2, decarbonisation of industry making the largest contribution over the rest of this decade period. What change does this translate into in practice – for example, for existing industrial facilities the balance between efficiency, fuel switching, scaling back and closure? What does government need to do ahead of time to mitigate impacts on jobs and local economies, and what does that imply for the pace of industrial decarbonisation decision makers are willing to sign up to?

- To what extent should agriculture emissions contribute to the overall pathway? Livestock emissions (mainly methane burped out by sheep and cows) barely fall at all in figure 2. Is this the right balance given the pace and scale of change in other sectors?

These are political, not technical questions. Within each a host of issues arise from the practicalities of drafting legislation through to the distributional impacts of the transition and how decision makers want to see these handled. The combined approach to setting plans and targets would not be able to settle these definitively ahead of time, but it would force decision makers to confront them explicitly, weighing them against their moral duty to confront the global climate emergency.