Social housing need of the hour amid homelessness crisis

Article

At a time when the social housing waitlist is weighed down with hundreds of thousands of people, the Scottish government has planned to reduce approximately £200 million in investment in social housebuilding. This could be disastrous and drive more people to homelessness.

Each passing month brings increasingly bleak news. Last year, Edinburgh took the lead as the first city council to declare a housing emergency. Glasgow followed suit shortly after. Prior to these developments, Argyll and Bute was the only other local authority to have taken such a step, and now Fife is slated to do the same.

These moves do not come as a surprise. In November last year, a survey from the Association of Local Authority Chief Housing Officers revealed that over half of Scotland’s 32 councils acknowledged failing to meet legal requirements in addressing the homelessness crisis. Shortly thereafter, the 2024 Scottish Homelessness Monitor issued a stark warning, predicting a 33 per cent surge in homelessness over the next two years. These alarm bells only seem like the beginning of the problem, with ALACHO further cautioning that more housing emergencies are likely to be declared in Scotland in the coming months.

The Scottish government appears to be doing precious little in the face of these challenges. In December, during the Budget presentation, finance secretary Shona Robison announced massive cuts to the Affordable Housing Supply Programme, a crucial funding source for social housing initiatives in Scotland. At a time when the social housing waitlist is weighed down with hundreds of thousands of people (official statistics indicate a waitlist of 178,000 people for social housing, the actual number could be as high as a quarter of a million), the government has planned to reduce approximately £200 million in investment in social housebuilding. This could be disastrous and drive more people to homelessness.

Access to high-quality clean, warm and safe housing can greatly impact mental well-being of an individual, fostering a sense of purpose and belonging within a community.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948 first codified the right to housing. Accordingly, investment in high-quality, affordable housing should be an urgent priority of the Scottish government.

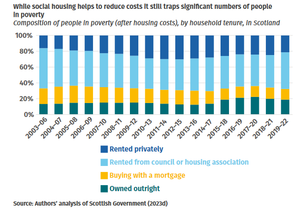

Our previous research has shown that social housing has the potential to lift individuals out of poverty and to simultaneously decrease the benefits expenditure due to its cost-effectiveness. This can, in turn, also reduce child poverty – a commitment made and reiterated by the Scottish government. Over the past decade, social housing has indeed been instrumental in addressing poverty, ensuring that 40,000-60,000 individuals remain above the poverty line, thanks to the affordability of social rents.

Historically, Scotland has maintained a lower rate of poverty after housing costs compared to England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. This has largely been attributed to a mix of higher housing density and lower social housing expenses. Worryingly, however, this gap has narrowed in recent times. There is now over £500 million allocated to ‘failure spend’ associated with housing, addressing issues stemming from low income, a flawed UK welfare system, and efforts to combat homelessness.

Between 2000 and 2010, there was a notable decrease in homelessness

applications in Scotland, but progress has stagnated in recent years.

Even more concerning is the fact that the proportion of children linked

to these applications has remained much the same, hovering at around 50

per cent. This means child poverty is nowhere close to being eradicated

as the government has pledged to do.

We have consistently advocated for heightened investment in social housing. The Scottish government’s ambitions, particularly its goal of constructing 110,000 affordable homes by 2032, with at least 70 per cent allocated to social rent, cannot be achieved without the requisite financial commitment.

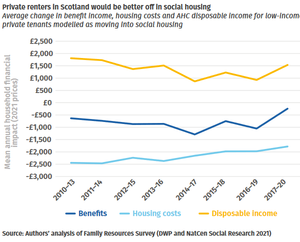

Our analysis shows that if throughout the 2010s, low-income people living in private rentals had been able to secure social housing, they could have experienced an annual reduction of approximately £2,200 in housing costs, received £800 less in benefits, and ended up £1,400 better off.

Our analysis also shows that 40,000 to 60,000 individuals, including 10,000 to 20,000 children, residing in social housing are shielded from poverty by avoiding private rentals. Conversely, 10,000 to 30,000 impoverished private renters could escape poverty by transitioning to social housing. However, it’s important to acknowledge that while social housing mitigates costs, a significant number of individuals still remain trapped in poverty after accounting for housing expenses.

If under these circumstances resources to social housebuilding are cut, the problem is compounded, leading to homelessness. Parents have shared their perspectives on housing with us, questioning the prevalence of empty houses and neighbourhoods.

'Why are there so many empty houses?' asked one. 'We went past on the bus, you will see one block with one house alive and the rest is dead… another block half broken,' said another.

The double whammy of financial insecurity and an uncertain housing market then manifests as an elevated risk of poverty. This not only pertains to individuals finding themselves without a home but also extends to cases where substandard housing poses safety concerns.

While the causes of homelessness are complex and interconnected, a strong correlation exists between poverty (as both a cause and consequence) and homelessness, as well as between health inequality and homelessness. One issue cannot be solved without addressing the other.

Quality housing not only addresses health disparities across society but also diminishes the burden on the healthcare system. A secure, warm, and stable home is crucial to Scotland’s ambition to become a fairer and more equitable nation. Investments in high-quality, affordable housing can break the cycle of poverty and enhance the overall quality of life. Ultimately, it will bring us closer to the aspiration of eliminating poverty in Scotland.

Related items

Tipping the scales: The social and economic harm of poverty in Scotland

In a country as rich as Scotland, the moral imperative to eradicate poverty is clear.

Budget to test Scottish government’s progressive credentials

With the UK government confirming real-terms spending cuts – all to fund tax cuts disproportionately benefiting the richest households – all departments face the risk of a return to austerity.

Achieving the 2030 child poverty target: The distance left to travel

On 27 March, the Scottish government will announce whether Scotland’s 2023 child poverty target – no more than 18 per cent of children in poverty – was achieved.