Taking back control in the North: A council of the North and other ideas

Taking back control in the North: A council of the North and other ideasArticle

Preface

‘The people of England deceive themselves when they fancy they are free; they are so, only during the election of members of parliament: for as soon as a new one is elected, they are again in chains, and are nothing.’

Jean-Jacques Rousseau,

The Social Contract (1762)

There is a widely held view that we shouldn’t talk about the structures and institutions of the so-called northern powerhouse. This view is promoted primarily by those who currently hold the reins: city leaders and chief executives, big businesses, government ministers and civil servants. But in this essay, I want to show that governance and the lack of subnational institutional capacity lies at the very heart of England’s productivity problem, and is key to addressing our democratic deficit.

I want to address two increasingly pressing questions.

- Who will drive industrial strategy for the north of England?

- How do we find ways for people in the North to ‘take back control’?

Although pressing, these are not popular questions. At the moment, they lie just beneath the surface of much discussion, but they need to be given greater consideration and voice. Not least because they sit at the heart of the malaise within Britain’s body politic, but also because they have the potential to restore a closer relationship between those who seek to run our cities and nations and the citizens with whom they hold power.

This essay makes a series of bold propositions about the state of our nation and the North in particular.

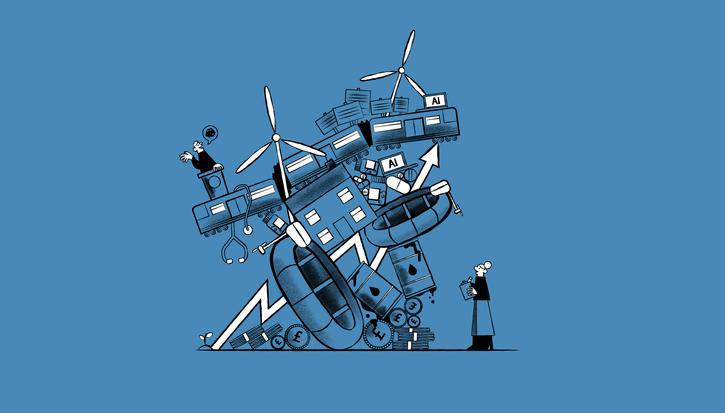

It argues that in order to address the severe economic imbalances affecting the nation, largely caused by globalisation, we are failing to identify the correct diagnosis of our problems and so wave after wave of industrial and regional policy tends to treat the symptoms (education, skills, transport, innovation, industrial location) rather than the more fundamental problem: our weak subnational institutions.

This problem is exacerbated by a highly centralised system of government which is hampered by a lack of spatial awareness and an inherent policy bias towards London and the South East. Over the decades, this has led to a culture of dependency in the regions, which are then dominated by supplicant elites. What holds this system of centralisation and dependency in place is not so much the might of government from the top down, but the weakness of any popular voice from the bottom up.

I argue that the call to ‘take back control’, which proved so salient for the Leave campaign during the EU referendum, was a more profound challenge to the way in which large institutions – particularly political institutions – are perceived to have disempowered large segments of the population, and that voting behaviours in the EU referendum have much in common with the Scottish referendum of 2014.

While ‘take back control’ is not in itself a call for greater devolution, let alone a more federal England, there is evidence that a return to some form of regional governance, if built around genuinely devolved powers and a reimagination of cultural and historical identity, could play an increasingly important role in addressing both the economic and democratic deficits felt so sharply in many parts of the North.

Any new form of subnational governance, however, needs to be developed at scale. While England is too big, our current city-regions and combined authorities are too small for the North to compete in a global economy. The scale most likely to be successful at galvanising a genuine northern powerhouse must encompass the 15 million people who live and work in the North West, the North East, and Yorkshire and the Humber.

Finally, this essay outlines short-, medium- and long-term proposals to develop the kind of institutional capacity that might be required to drive forward this northern super-region. These include: developing and improving the pan-northern institutions that already exist; establishing a formal Council of the North; and finally, breaking the existing pattern of electoral representative democracy and re-establishing the North at the forefront of democratic innovation with the development of a more deliberative Northern Citizens Assembly.

There is of course no particular reason why the ideas in this paper couldn’t be applied elsewhere in England – or, indeed, they might require an all-of-England approach – but there are many historical precedents where ideas ‘made in the North’ resulting from distinctive northern concerns have gained national and sometimes global credence. It is arguable that the north of England has been a fulcrum for democratic innovation just as much as it has been for science and industry. It is in that pioneering spirit that I offer this essay.

Related items

The great enabler: transport’s role in tackling environmental crises and delivering progressive change

In this special issue of IPPR Progressive Review we bring together leading political, academic and civil society thinkers to consider transport in modern Britain and its role in delivering a healthier, greener, more prosperous and…

The shape of devolution

How do we create transparent, fair and practical footprints for local power across England?

Everything everywhere, all at once: The need for a four nations approach to accelerate wind deployment in the UK

The UK is a world leader in wind deployment and has some of the most ambitious future wind capacity targets in the world, aiming for clean power by 2030.