Time for a new progressive alliance

Article

To many in the Labour party there must seem little reason why they should spend much time mending fences with the Liberal Democrats right now. After all, immediately after the 2010 general election Nick Clegg's party readily sold its soul to the Conservatives, ensuring that Labour was put out of power and paving the way for a Tory attack on the public sector and the poor. In the meantime, many Liberal Democrat voters have switched back to Labour, leaving their former party on course for electoral disaster and ensuring that Labour already looks perfectly capable of regaining power in 2015. Rather than revisiting former hopes of a 'progressive alliance' between the two parties, Labour should surely now simply leave the Liberal Democrats to writhe uncomfortably in the coalition bed in which they have chosen to lie?

Such a reaction is natural. Yet it could also prove very short-sighted. While Labour will undoubtedly want to win over and retain the votes of as many former Lib Dem voters as possible, it should not underestimate the potential value to the party of fostering good relations with the Liberal Democrats. The quality of the relationship between the two parties could well prove crucial to Labour's prospects of future power - before or after 2015.

To date, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition has held together quite well. Yet gradually the tensions are mounting. During the first 12 months of the Coalition government the Liberal Democrats were so keen to demonstrate that the two parties could work effectively together in government that they eagerly claimed full ownership of more-or-less everything the Coalition did. This included - most disastrously of all from their point of view - the decision to increase English university tuition fees to as much as £9,000 per annum. However, humiliating defeat in the alternative vote (AV) referendum, together with a drubbing in the 2011 local and devolved elections, put paid to that approach. In the last 12 months the Liberal Democrats have increasingly sought to differentiate themselves from their coalition partners, most notably by openly making their demands known in the run up to the 2012 budget.

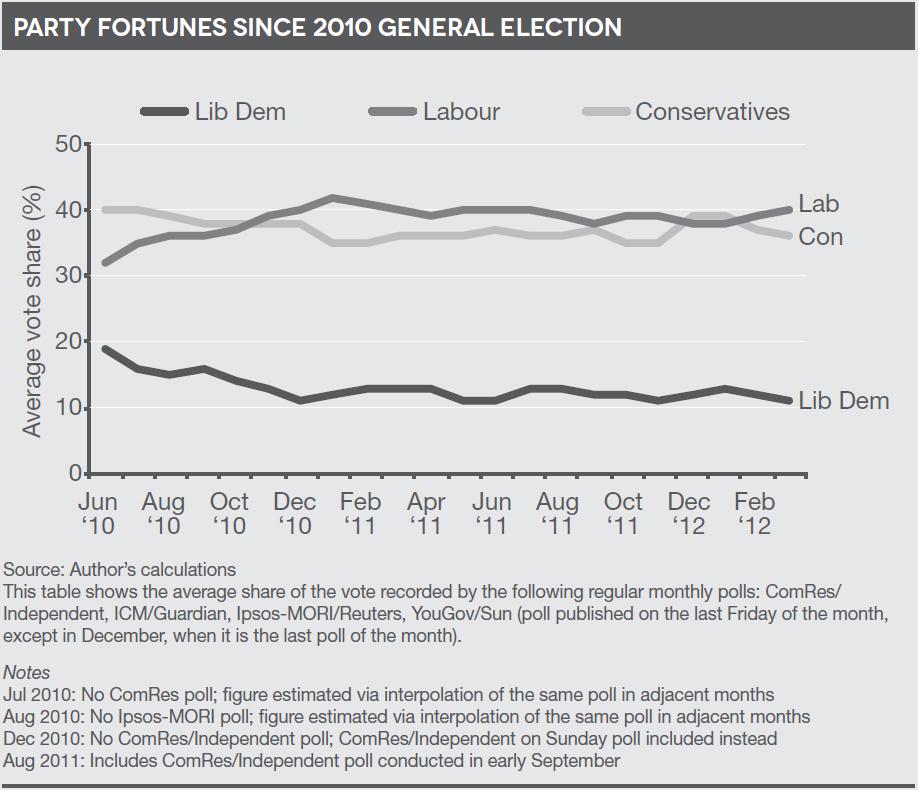

Yet, as the following chart shows this change of tack has so far brought the party little reward - the Liberal Democrats have continued to average between 11 and 13 per cent in the polls, while their overall performance in this month's local elections was no better than twelve months ago. Equivalent figures for April 2012 were 33 per cent for the Conservatives, 40 per cent for Labour and 11 per cent for the Liberal Democrats.

The longer this situation prevails, the more concerned party activists and MPs will become about their future prospects - and the more brittle relations between the two Coalition partners will be. In those circumstances some unexpected event or row might just cause those relations to snap, provoking the withdrawal of all or most Lib Dem MPs from the Coalition.

Should that happen, the so-far little-appreciated provisions of the Fixed Terms Parliament Act would come into play. These provisions constitute a fundamental rewrite of the rules of the Westminster game. They have taken away from the prime minister the right to call an election at a time of his own choosing. An early election can now only happen if either:

- a motion of no confidence has been passed in the government, and thereafter no new government is formed within 14 days, or

- at least two-thirds of MPs vote for an early dissolution.

With these provisions in place, David Cameron's options in the event of a break-up of the Coalition would significantly depend on the state of relations between Labour and the Liberal Democrats. If they were still in electoral trouble, the last thing the Liberal Democrats would want to precipitate is an early election. They would thus be unlikely to back a motion of no confidence in what would under these circumstances be a Tory minority administration - unless, that is, there was an understanding that if the government were to be brought down a new coalition between Labour and the Liberal Democrats would be formed instead. And while right now the parliamentary arithmetic means that sustaining a Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition would be difficult, the task would look a lot easier if between now and then Labour had captured three or four Tory seats in parliamentary by-elections. This is by no means an unrealistic prospect, given that since 1979 governments have on average lost four by-elections per parliament.

Of course, if they thought they could profit from an early ballot following a coalition collapse, the Conservatives themselves could attempt to force an election by putting down and voting for a motion for dissolution. If Labour backed it as well, the necessary two-thirds majority would easily be acquired irrespective of how the Liberal Democrats voted. But Cameron would not want to take that step if he felt there was any risk that rather than leading to an early election such a manoeuvre might instead precipitate coalition talks between Labour and the Liberal Democrats. In short, if relations between Labour and the Liberal Democrats were such that there simply appeared to be some possibility that they might do a deal, Cameron's room for manoeuvre would be constrained and Labour would be left with a stronger hand to play.

But what of the position after the 2015 election? Surely there is little likelihood that Labour will need to be talking to the Liberal Democrats then? After all, Britain's single-member plurality system has usually produced an overall majority for the largest party, and thus the chances that it will fail to deliver such a majority for a second time in a row must surely be remote indeed? So long as Labour manages to outpoll the Conservatives should it not be home and dry?

However, the hung parliament brought about by the 2010 election was no accident. It was a consequence of long-term changes in pattern of party support that mean it is now persistently more difficult for either Labour or the Conservatives to win an overall majority. Meanwhile, although the current review of parliamentary boundaries will not deliver the Conservatives quite the bonus for which they were hoping, it will undoubtedly make winning an overall majority more difficult for Labour than it otherwise would have been.

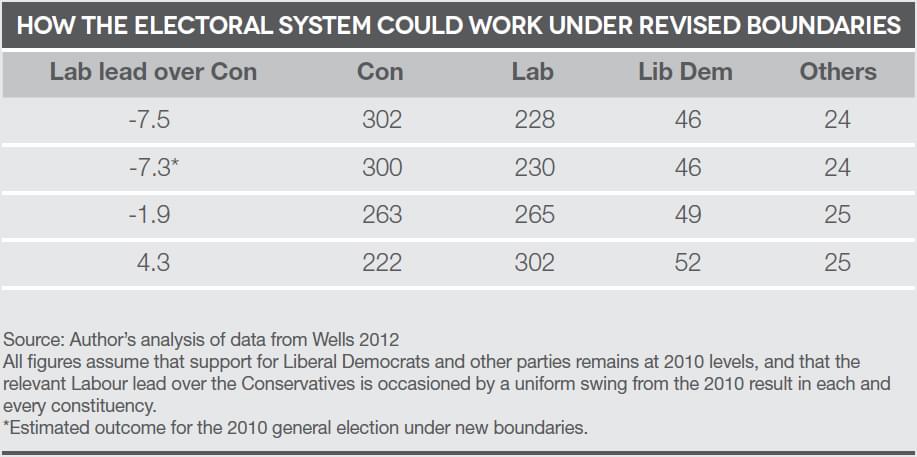

If single-member plurality is to deliver overall majorities for one party on a regular basis then two conditions have to be satisfied. First, the system needs to deny anything much more than token representation to third parties. Second, there have to be plenty of seats that are marginal between the two largest parties, such that a narrow lead for one party in the polls can be readily translated into a majority of seats. Neither condition is satisfied as well now as it once was. At the last three elections, on average, no less than 86 seats, or 13 per cent of the total, were won by parties other than Labour and the Conservatives. In contrast, over the course of the seven elections between 1950 and 1970 the average level of third-party representation was just 11 seats. Meanwhile, at the last three elections rather less than one in five seats has been closely fought between Labour and the Conservatives, compared with well over a quarter in the '50s and '60s. The boundary review will do little to change this situation. This can be seen if we analyse Anthony Wells' estimates of what the outcome of the 2010 election would have been in each constituency if the Boundary Commissions' provisional proposals had been in place. Such an analysis shows that just 16 per cent of seats would have been marginal between Labour and the Conservatives, while third parties would still have won 12 per cent of the seats.

However, in contrast to what actually happened, the Conservatives would according to Wells' estimates have been tantalisingly close to victory - with 300 seats they would have been just one short of an overall majority. A voting lead of 7.5 points would have been sufficient to deliver the Tories an overall majority, far less than the 11.2-point lead the party would have needed under the current boundaries and pattern of party support. Although the lead Labour would require under the new boundaries is, at 4.3 points, still lower than that required by the Tories (primarily because of the lower level of turnout in Labour-held seats), it is still noticeably higher than the 2.7-point lead the party needs under the current boundaries.

On its form so far in this parliament that is not a target that Labour can be confident of reaching. Despite the backdrop of economic austerity and stuttering economic growth, since the 2010 election the party's average lead in the regular monthly polls has been above four points in only three months out of 23, as figure 1 shows. Bearing in mind that oppositions often fare better in mid-term than when an election is approaching, such a performance hardly looks like a sound basis on which to look forward with confidence to a Labour overall majority in 2015. Rather, it would appear to point to the prospect of Labour being the largest party in a hung parliament.

Still, there might be a crucial flaw in this analysis of the implications of the new boundaries: it assumes that the Liberal Democrats are still as popular in 2015 as they were in 2010. Yet we have already seen that that looks like a dim and distant prospect. However, even if we were to assume that in 2015 the Lib Dem vote were to halve from what it was in 2010 - which is where the party has consistently sat in the polls ever since their volte face on tuition fees - the possibility of a hung parliament still cannot be discounted.

On that assumption, the Conservatives would still need a 3.3-point lead to secure an overall majority, while Labour would need a lead of 2.2 points - not much below the average lead of 3.2 points the party has enjoyed in the polls since it first pulled ahead in November 2010. Moreover, this analysis points to the asymmetric consequences of any collapse in Liberal Democrat support. Such a scenario results in no less than a 4.2-point drop in the target the Conservatives require for an overall majority, whereas the target Labour would need to meet falls by only half of that - 2.1 points. Although such support is less strongly concentrated in predominantly Conservative territory than it once was, the Conservatives would still be the main beneficiaries of any collapse in Lib Dem support - thereby making it much easier for the Tories in particular to win an overall majority.

So as deep as the Liberal Democrats' problems may be, Labour cannot afford simply to ignore them. As Ed Balls recognised in a revealing interview with the Independent shortly before Christmas, it might yet prove to be to Labour's advantage to be in a position to wheel and deal with the Lib Dem leadership, either before or after the 2015 election. And one of the lessons of the coalition negotiations in 2010 is that when the chips are down, preparation and prior contacts matter. In 2010, the Conservatives were ready and willing to do a deal, while previous contact had given Cameron and Clegg reason to believe they could work together. Labour, by contrast, was ill-prepared and internally divided on its willingness to strike a deal with the Liberal Democrats, while personal relations between key personnel in the two parties were poor. So while Labour will doubtless continue to mock and berate the Liberal Democrats in public, in private the party would be wise to keep the potential lines of communication open.

Related items

The homes that children deserve: Housing policy to support families

As the government seeks to develop a new child poverty strategy, it will need to grapple with housing – the single largest cost faced by families.

Powering up public support for electric vehicles

Tackling greenhouse gas emissions will only work if public support for action remains strong. That means ensuring tangible improvements in people’s lives and heading off any brewing backlash.

Assessing the economy

Over the past few days and weeks, there has been lots of rather histrionic commentary about the UK’s economic situation as if the budget has created an economic disaster from which we’ll never recover.