What would the illegal migration bill mean in practice?

Article

Introduced to the Commons earlier this month, the new illegal migration bill represents the UK government’s latest attempt to respond to the recent rise in people crossing the English Channel in small boats to claim asylum. The core purpose of the bill is to deter people from crossing the Channel through a series of punitive measures targeted at those who arrive by irregular means. The government claims that it wants to ‘stop the boats’. But as this article argues, the measures seem more likely to open up a Pandora’s Box of ethical, legal and practical issues which risk backfiring on the Home Office in a number of ways.

At the heart of the bill is a duty on the home secretary to remove everyone who enters or arrives in the UK without permission on or after 7 March 2023. Any asylum claim must be considered permanently ‘inadmissible’ – that is, it is regarded without consideration. People may either be removed to their home country or to a different safe country, though those who make an asylum claim can only be returned home if they are from a list of specified safe countries. The main exception to the duty to remove is for unaccompanied children, but even here the home secretary has a power to make arrangements for removal, and when unaccompanied children turn 18 the duty to remove kicks in once again.

There are corresponding powers to detain people arriving without permission, with strict limits on whether it is possible to grant bail in the first 28 days of detention. These powers would apply in spite of current protections limiting the use of detention for families, unaccompanied children and pregnant women. The legislation also includes provisions to ensure that people can be removed from the UK while a legal challenge to their removal is taking place, unless the claim is based on the Home Office making a factual mistake over whether the removal duty applies or it is based on there being ‘a real risk of serious and irreversible harm’ from being removed to a third country. And there are further provisions preventing, in most cases, people who the home secretary has a duty to remove from getting leave to enter or remain or citizenship in future.

The message of the legislation is clear: people arriving in the UK by small boat – or, for that matter, by any other irregular route – will be blocked from claiming asylum here and removed as swiftly as possible. But the real-world implications of the bill are not so simple. The consequences are likely to be a lose-lose for both people seeking asylum and the Home Office itself.

The consequences are likely to be a lose-lose for both people seeking asylum and the Home Office itself.

First, it is unlikely to be feasible for the Home Office to remove every single person who arrives in the UK irregularly. Under the legislation, people who have made an asylum claim can only be returned to their home country where this is either an EU (or EEA/Swiss) member state or Albania. In all other cases, people must be sent to a safe third country which is willing to accept them (or to the country where they embarked for the UK). Given that three quarters of detected attempts to enter the UK irregularly in 2022 were from countries not on the list for safe returns, this means that a large majority would need to be removed to a safe third country.

Yet as things stand, the only third country the UK has an agreement with for removals is Rwanda. Last weekend the home secretary visited Rwanda with the intention of making the case that large-scale removals to Rwanda would be possible by the summer. But the reality is more complex. The deal continues to face significant legal challenges after the first flight to Rwanda was halted in June 2022. In December 2022, the High Court concluded that relocating asylum seekers to Rwanda is lawful, but this decision has been granted permission to appeal. No one can be removed to Rwanda until the litigation process is complete.

Moreover, there are financial and logistical challenges to removing people at scale to Rwanda. Outside of the £120 million promised to Rwanda when the deal was first announced, additional funding will be provided for each person relocated to cover accommodation and case processing costs. And the annual costs of removing people out of the country by chartering flights can rack up to millions.

Rwanda’s capacity to scale up its asylum system to handle thousands of asylum applications is also dubious. Figures from UNHCR show that in 2021 Rwanda only received 408 asylum applications and made only 487 asylum decisions. Notably, the number of new asylum applications made by people from Rwanda to other countries in the same year was nearly 13,000 – around 30 times the number of asylum applications received in Rwanda.

Notably, the number of new asylum applications made by people from Rwanda to other countries in the same year was nearly 13,000 – around 30 times the number of asylum applications received in Rwanda.

Moreover, this is not the first time a similar deal has been struck with Rwanda. Between 2014 and 2018, Israel ran a scheme where some Eritrean and Sudanese people were offered resettlement payments and a flight to Rwanda as an alternative to imprisonment. However, it was found that they were not given the opportunity to make an asylum claim in Rwanda, and almost all were thought to have left the country, accessing people smuggling routes across Europe. There is a risk that the same dynamic could occur in the context of the UK -Rwanda deal, ultimately leading to its unravelling.

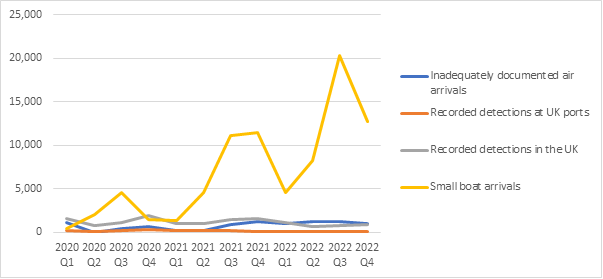

There have been suggestions that the government will not need to remove large numbers of people, because the very passing of the legislation will deter new arrivals. But the historical evidence suggests that the bill will not have a sufficient deterrent effect to stop people making irregular journeys. Australia’s efforts to similarly ‘stop the boats’ through offshore processing in Nauru and Papua New Guinea proved to be a costly failure. And the UK government’s attempts in recent years to deter arrivals by restricting asylum rights appear to have had little effect on numbers: in fact, there has been an increase in small boat arrivals since the Rwanda plan was originally announced last April.

Fig 1: Detected attempts to enter the UK irregularly (2020 – 2022)

Proponents of the plans argue that the threat of removing everyone to Rwanda could be a gamechanger for asylum seekers considering whether to cross the Channel. But this relies on the people making the journey having reliable and up-to-date information about the UK’s asylum system, which is highly debatable. Given numbers have continued since the Rwanda plan was announced, it seems likely that the policy would have to be enacted at scale to change enough people’s minds to stop small boat arrivals entirely. As we have explained, removing everyone who arrives is unlikely to be feasible, unless the numbers coming fall significantly. The argument therefore becomes circular: to deter enough people, the policy must first be implemented, but for it to be implemented, it must first deter enough people.

The more plausible reality, then, is that large numbers of people will be stuck in limbo in the UK – unable to claim asylum, unable to be removed, and unable to work or claim mainstream benefits. Assuming that it will not be legal or practical to detain them indefinitely, this will leave a large – and likely growing – number at risk of destitution. They may be eligible for Home Office section 4 support, which includes accommodation and a weekly payment of £45 (via a payment card). However, this support can only be provided in certain circumstances – for instance, where the individual is taking all reasonable steps to leave the UK, where they are unable to leave the UK due to a physical impediment to travel or some other medical reason, or where support is needed to avoid a breach to their human rights – so it is not yet clear what the Home Office would offer to this group. Local authorities, too, may provide support to people in certain circumstances – eg under their duty to promote and safeguard the welfare of children.

Others may seek to avoid the government altogether – either by making journeys to the UK through clandestine means (eg lorry drops) or disappearing into the shadow economy once they get the chance. This could mean large numbers working and renting without permission and support, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, as we argued previously in our report on the hostile environment. The likely end result of this legislation is therefore a growing number of people in the UK – many of whom will have a well-founded claim to asylum – either destitute, in irregular work, or accommodated by the state, or some combination of all three.

The likely end result of this legislation is therefore a growing number of people in the UK – many of whom will have a well-founded claim to asylum – either destitute, in irregular work, or accommodated by the state, or some combination of all three.

Finally, the bill also threatens workable solutions to the Channel crossings. The legislation will send the message internationally that the UK is foregoing its responsibilities under the Refugee Convention. This could hinder future cooperation with France and the EU, including any potential negotiations on a ‘Dublin-style’ arrangement for determining which countries are responsible for processing asylum claims.

The bill also makes returns to many countries impossible. When people arrive irregularly and make an asylum claim, the bill ensures that it will be dismissed and they can only be returned home if they are from a list of eligible safe countries (including EU/EEA countries, Switzerland and Albania). Of the 3,453 enforced returns to home countries in the year ending September 2022, 2,579 were nationals of countries on this list; the remaining 874 (around a quarter) were from other countries.

It is notoriously difficult to predict future migration flows and the impacts of policy decisions. But it is hard to see how this bill resembles anything close to a solution to addressing the UK’s dysfunctional asylum system. Instead, all the evidence points to this creating more chaos, further marginalising those seeking refuge, and rebounding on the Home Office itself.

Related items

Reclaiming social mobility for the opportunity mission

Every prime minister since Thatcher has set their sights on social mobility. They have repeated some version of the refrain that your background should not hold you back and hard work should be rewarded by movement up the social and…

Facing the future: Progressives in a changing world

Realising the reform dividend: A toolkit to transform the NHS

Building an NHS fit for the future is a life-or-death challenge.