Why the way Scottish budgets work needs to change

Article

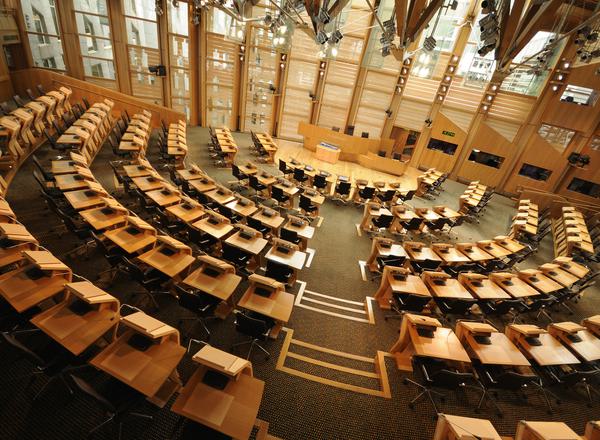

Today marks one of the most important days in Scottish parliamentary life: the budget, when the Scottish government will set out its plans for tax and spend within the limits of the current devolution settlement.

While it’s tempting to view the two events at Holyrood and Westminster as analogous, we should be cleareyed about the distinct nature of Scotland’s budgetary process. Firstly, the immediate challenge for cabinet secretary Shona Robison is negotiating her budget through parliament, a task made more difficult following the collapse of the Bute House Agreement which saw the Scottish Greens exit government.

To stave off an early Holyrood election, SNP ministers have appealed to opposition parties, with negotiations set to go to the wire. It is not yet apparent what complexion the budget will take. But what is deserving of far more attention is the way Scottish budgets have become hyper reactive to the changing politics of Westminster.

Even as Holyrood has diverged from successive UK governments, decisions made at Westminster still heavily impact what is possible or desirable in Scotland. The Barnett Formula links spending increases in England to the size of Block Grant available to the Scottish government. However, with income tax now largely devolved, along with some social security benefits, there is increased complexity in how Scottish and UK budgets interact.

It has become increasingly important for governments on both sides of Hadrian’s Wall to recognise how their respective budgets interact and impact each other

The Scottish budget has assumed greater responsibility for both raising its own revenues and securing the financial wellbeing of citizens through social security. Block Grant Adjustments (BGAs) remove funding to reflect the Scottish government’s revenue raising powers and add funding to reflect its responsibility for some social security benefits[1]. Therefore, it has become increasingly important for governments on both sides of Hadrian’s Wall to recognise how their respective budgets interact and impact each other. One issue which demands urgent (and longstanding) cross-border budgetary cooperation is realising Scotland and the UK’s net zero transition.

There is perhaps no policy area where there is greater interdependency and cooperation required between devolved and central government than in achieving the stated goal of net zero. Scotland comprises a third of the UK’s land mass, a great deal of the reforestation and peatland restoration potential, but less than 10% of the UK population. This poses a problem as under the current devolved settlement, responsibility for environment, and funding the net zero transition, falls on Holyrood’s population-determined budget. Therefore, as the Scottish Fiscal Commission points out, the “fiscal burden” of reaching the UK’s net zero target “may fall disproportionately on the Scottish Government”. Responding to a changing climate has heaped pressure on the sustainability of the fiscal status quo so it is important for the UK government to be flexible and realise where cross-border challenges require scaling budgets beyond the limits of the current Fiscal Framework.

Despite these long-term cross-border challenges, Scotland’s approach to budgets has become increasingly short-termist. Tumult at the top of the SNP in recent years has resulted in changes in leadership, and harmful, politically expedient policies like a Council Tax Freeze which has further diluted local democracy and accountability and undermining public services despite increases in UK government public spending.

What is worse, the need to make up for a bout of myopic economic decision-making on tax and spend has left Robison trying to balance the books in day-to-day spend by dipping into Scotwind monies, a windfall from offshore wind leases that is meant to be dedicated to fund long-term investments in the green transition and tackling the climate emergency. Scotland is paying the price for unpredictability budget-to-budget, with longstanding issues compiling, in the form of missed targets on new social housing and the green heat transition, and stalled progress on reducing child poverty.

The way Scottish budgets work needs to change to prioritise the future. Change too is needed in the way that economic decision-making between the UK and Scottish governments works, so that it is better coordinated and transparent - as well as moving beyond the UK’s own erratic decision-making (like Trussonomics) which makes devolved policymaking more difficult. A serious conversation is needed about the long-term fiscal future of Scotland, and that means rethinking tax and spend, and committing to preventative spending to build resilience for the storms ahead. With politicians across the chamber looking to the 2026 Holyrood election just around the corner, they must avoid the convenient trap of short-termism.

Casey Smith is a researcher at IPPR Scotland

[1] For a fuller understanding of the ins and outs of Block Grant funding in Scotland, the Scottish Fiscal Commission has handy explainers

Related items

Achieving the 2030 child poverty target: The distance left to travel

On 27 March, the Scottish government will announce whether Scotland’s 2023 child poverty target – no more than 18 per cent of children in poverty – was achieved.

Women in Scotland: the gendered impact of care on financial stability and well-being

Women in Scotland are far likelier than men to take on childcare and other caring responsibilities, which puts them at an economic disadvantage.

A helping hand for the helpers - a plan to recognise Scotland's unpaid carers

A Minimum Income Guarantee pilot would empower carers to take control of their own lives and regain some independence from a state that has become overly reliant on their unpaid labour and goodwill to function.