Making the vulnerable visible: Narrowing the attainment gap after Covid-19

Article

Introduction

Covid-19 has been the biggest disruption in education since the Second World War and will have long-lasting effects on students. Since March 2020, schools have been mostly closed with only the children of key workers and identified vulnerable children invited to attend. Most children in England have been expected to learn remotely. The government also took the unprecedented decision to cancel SATs, GCSEs and A-Levels for 2019/20 and to put Ofsted inspections on pause during the pandemic.

The government is now aiming for all children to be back in school from September. But the pandemic will undoubtedly have long-lasting impact on students. The evidence is clear that extended periods away from school can result in significant ‘learning loss’, particularly for disadvantaged pupils. In June the government announced a £1 billion “Covid catch up plan” for primary and secondary schools to support catching up on learning lost during lockdown, with schools encouraged to put in place one-to-one and group tuition to narrow the attainment gap. This is an important step in the right direction, but it will not be enough on its own to make up for the damage done during lockdown.

Vulnerability, schooling and Covid-19

Without action to address a widening ‘vulnerability gap’ we will fail to improve attainment for those furthest behind. Academic support - such as access to tutoring and laptops - are factors in educational underachievement. However, lying behind the country’s long-standing attainment gap is the wider set of inequalities faced by children and young people outside the classroom which can form barriers to their learning. Whilst many children and young people grow up in happy and healthy homes, some have to learn whilst coping with their own and their families’ mental ill-health. At the extreme, young people might face domestic violence, serious mental health problems, family addiction and neglect, sexual or psychological abuse. These experiences have a big impact on learning. Those children who require a social worker to intervene to support them are the children most likely to underperform at school. They are seven times more likely to achieve in the lowest decile in their GCSEs than those without a social worker and are the most at risk of not being in education, employment or training afterwards. Furthermore, the evidence is clear: this type of vulnerability overlaps with financial deprivation and yet – when factors like poverty are held constant – can be a more significant factor in educational failure. This can be thought of as a ‘vulnerability gap’.

The pandemic has both exacerbated the vulnerability of children and highlighted their needs within schools. Tragically, the pandemic is likely to have worsened the difficult situation in which many vulnerable children live, as well as creating a new group of children facing damaging experiences outside school. Before lockdown, 1 in 10 children in the school population had needed a social worker. Emerging data suggests that domestic abuse and mental ill-health has since increased significantly as a result of the pandemic. The economic consequences of Covid-19 is likely to make this worse still. Fortunately, many schools have stepped into the breach to support these pupils, going beyond the school gates to deliver work, food and safeguarding visits – often when social services teams themselves have struggled to do so. The government have also prioritized this group, taking the laudable step of making schools responsible for identifying their “vulnerable” learners who needed to continue attending during lockdown. This created greater – albeit temporary – visibility of these students.

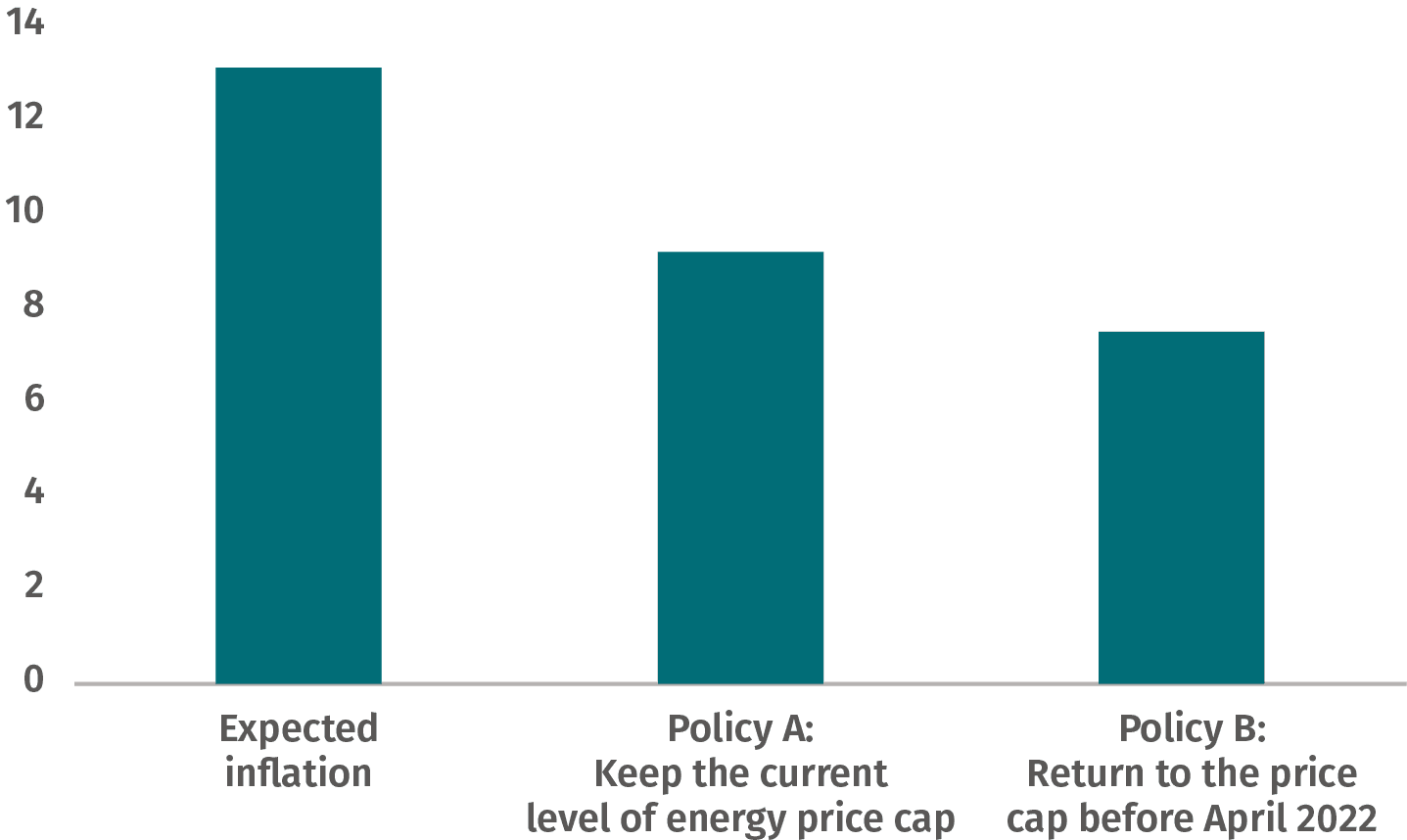

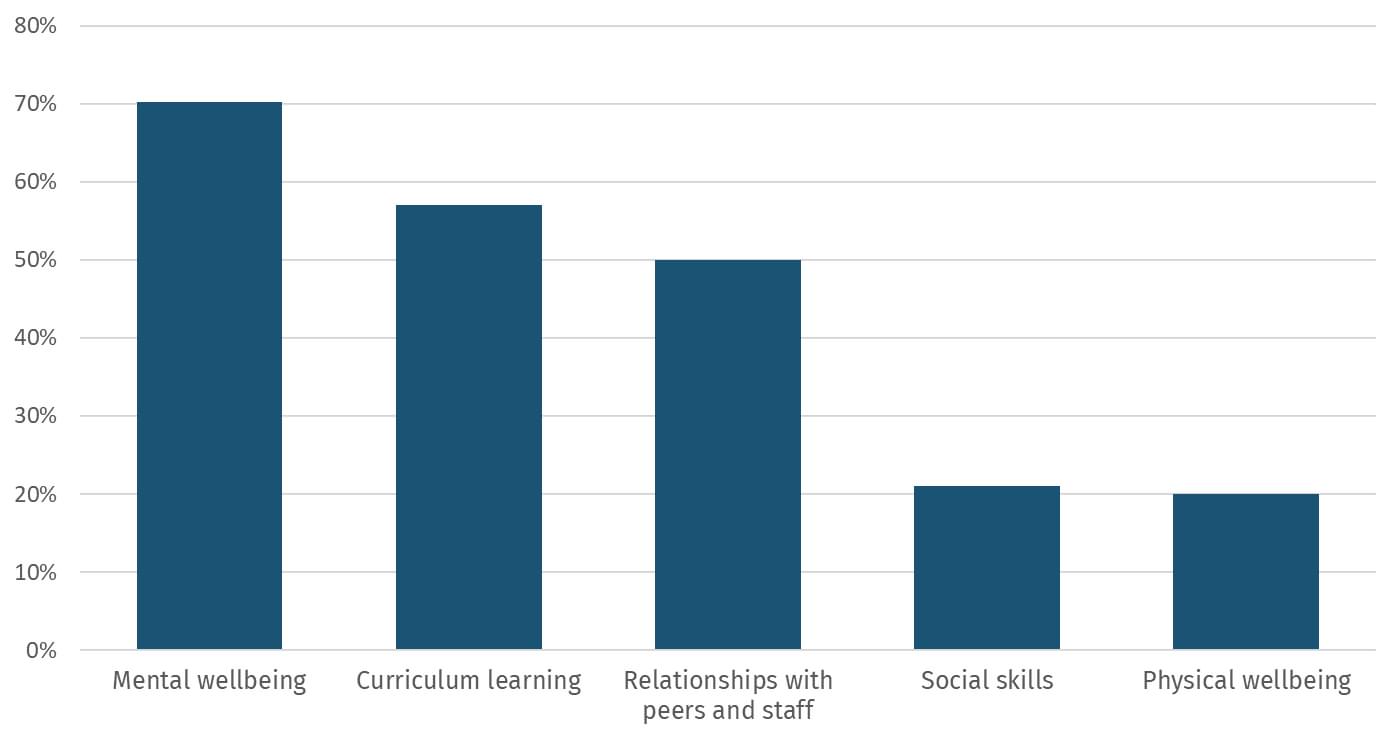

Both teachers and parents agree that addressing the ‘vulnerability gap’ must be a priority. Without resource and focus to address pupil vulnerability, schools will have limited ability to close the attainment gap, or recover ‘lost learning’ for those children who have suffered the biggest social, emotional and academic impact during the lockdown. New polling conducted by Teacher Tapp for IPPR shows nearly three-quarters (71 per cent) of teachers feel that additional support for mental ill-health and other social stressors is needed to close the poverty attainment gap (see figure 1). Likewise, 70 per cent of parents said a focus on mental health should be a priority when children go back to school (compared to half who wanted focus on curriculum learning) (see figure 2).

Figure 1: Teacher responses to the statement: Unless there is greater support for pupils who have experienced bereavement, domestic abuse and other deteriorations in mental health as a result of COVID-19, I will struggle to close the ‘attainment gap’ regardless of any additional academic support provided.

Source: Teacher Tapp polling for IPPR

Figure 2: Parent responses to the questions:What do you think schools should focus on when your child does return to school?

Source: Parentkind

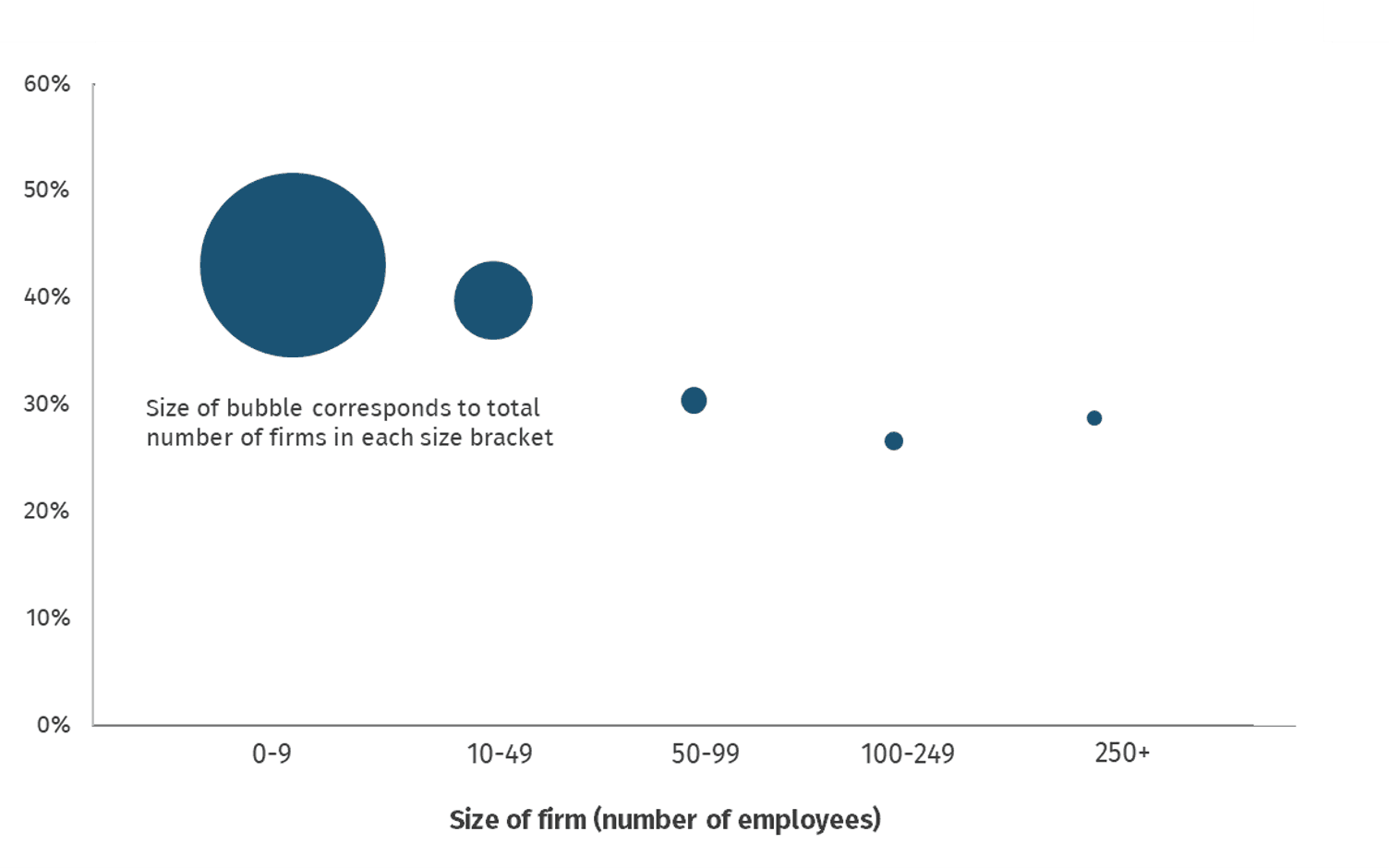

Figure 3: Teacher responses to: Do you feel confident in knowing if any of the pupils you teach have experienced any of the following during lockdown?” and “Which of the following experiences are you confident you have the knowledge to effectively support a child you are teaching through?

Source: Teacher Tapp polling for IPPR

Policy recommendations

The government should introduce a package of support to address the growing ‘vulnerability gap’, alongside their existing ‘Covid catch up plan’. We recommend three measures that government should pursue as the new school year begins:

1. Formalise a process by which VulnerableChildren are identified

Children who are thought to have Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) are identified by schools before their need has escalated to requiring an Education and Health Care Plan. As a result, teachers are aware of who they are and the need to provide them with additional support so they can achieve. Meanwhile school governors, Ofsted and national government can compare their outcomes to those of other children in the school. The same is true for children from poorer families (identified via their need for free school meals).

However, as we have set out, there is a large group of young people who are vulnerable as a result of home circumstances who are often invisible to frontline teachers, and those who hold schools accountable. New polling conducted by Teacher Tapp for IPPR confirms this. It finds that half of teachers do not feel confident that they know which children have experienced bereavement, abuse, parent mental health and new family caring responsibilities during the Covid-19 lockdown (see figure 3). We call on the government to correct this by requiring schools to identify and report data on students they believe to be vulnerable, beginning in September this year, as children return to school. This information should be linked to young peoples’ Unique Pupil Numbers, so their outcomes can be tracked and transparent within the National Pupil Database.

2. Commit to providing schools with extra financial support for the most vulnerable learners (on Child Protection Plans) through a new ‘Vulnerability Premium’

Despite the extra work many schools have been doing during lockdown to support vulnerable learners, there is currently no extra school funding for the majority of vulnerable children (except those taken into care via the “Looked After Premium”). This contrasts with other groups of students who need additional support, for example poorer children and those with special needs who receive funding through the pupil premium and Education and Health Care Plans. This is despite the fact that outcomes for these kids (e.g. those on a Child Protection Plan) are often as bad if not worse than those other groups. Building on a recommendation of the Education Policy Institute, we call on government to at least match their catch-up funding of £1 billion for next year and (on a recurring basis) to extend the Looked After Premium to become new “Vulnerability Premium”. This wouldcater for children who have historically needed a Child Protection Plan.

3. Enable schools and wider public services to address the root causes of vulnerability

Teachers have an important role in identifying vulnerable children but they are not always trained to support these young pupils. Our polling with Teacher Tapp shows that more than half do not feel confident in supporting children through bereavement, additional caring responsibilities, abuse and mental ill-health (see figure 3). The government should work with schools to provide teachers with additional training to feel more confident in supporting children to return to school and learn, in the wake of these challenges during lockdown.

For those children whose families are in crisis, the most effective work in schools will require additional support from children’s social care and mental health services. Yet the evidence is clear that too often accessing these services - and their integration with educational professionals - is inadequate. Embedding social workers and mental health specialists in schools has proven to be effective in identifying those in need of support and improve outcomes. We therefore call on government to invest in developing effective models of co-located mental health and social work services in schools.

Related items

Reclaiming social mobility for the opportunity mission

Every prime minister since Thatcher has set their sights on social mobility. They have repeated some version of the refrain that your background should not hold you back and hard work should be rewarded by movement up the social and…

Facing the future: Progressives in a changing world

Realising the reform dividend: A toolkit to transform the NHS

Building an NHS fit for the future is a life-or-death challenge.