Migrant workers and coronavirus: risks and responses

Article

In this short briefing, we set out the economic risks for migrant workers posed by the current Coronavirus crisis and propose a number of urgent measures in response, in order to provide a social safety net and promote public health.

Drawing on data from the Labour Force Survey, we find that migrants are more likely to be working in industries affected by the crisis, including accommodation and food services. Moreover, migrants are more likely to be self-employed and in temporary work, putting them at particular risk of losing their livelihoods as a result of the crisis. Finally, migrants are far less likely to own their own home and more likely to be in private rented accommodation, placing their households in a financially precarious situation as the coronavirus emergency develops.

Yet despite these risks, many migrants in the UK have only a limited social safety net, given that visa conditions often include barriers to accessing public funds. This means that migrants face the unenviable choice of continuing to work in spite of the health risks or losing their livelihoods. This poses a significant danger to both individual workers and to efforts to minimise the transmission of the virus. We therefore propose emergency measures to lift restrictions on access to benefits and public services, in order to limit the economic fallout of coronavirus and protect public health.

Context

In response to the rising number of Covid-19 cases, the government has introduced a swathe of social distancing measures to suppress the transmission of the virus, including requiring people to leave their homes only for essential purposes, closing schools, and shutting down restaurants, pubs, hotels and non-essential retail stores. This has had an immediate economic impact, including a significant reduction in economic activity and substantial job losses. To mitigate these impacts, the government has responded with a large package of measures, ranging from offering £330 billion in business loans to covering up to 80 per cent of wages for employees who are furloughed and kept on employer payrolls. Critics have noted, however, that the government’s proposals do not provide the same level of protection for some workers – for instance, the self-employed.

As the crisis develops, there has so far been little analysis of the risks posed for migrant workers due to the pandemic and the government’s new measures. Migrants face particular restrictions on access to welfare and public services, so any additional risks as a result of coronavirus could have significant implications for their lives and the wider public. This analysis will bring together different pieces of evidence on the status of migrant workers to explore their position as the crisis unfolds. The analysis includes:

- The industry profile of migrant workers and how this might affect the risks posed by the current economic turbulence

- The employment status of migrant workers and how this affects their ability to access government support

- The housing tenure and accommodation conditions of migrant households and how this could impact their experience of the crisis

Analysis

We have analysed the latest round of the Labour Force Survey (conducting during the final quarter of 2019) to assess the risks of the coronavirus crisis and the government’s social distancing measures on migrant workers. For this analysis, we have defined migration on the basis of country of birth, in line with other studies.

The main findings of the analysis are as follows:

Migrant workers are particularly likely to work in accommodation and food services, one of the most exposed sectors in the crisis

The government has asked all hotels, restaurants, and non-essential shops to close, placing significant strain on the UK’s hospitality industry. Our analysis suggests this will have a particular effect on migrant workers: around 9 per cent of EU workers and 7 per cent of non-EU workers are employed in accommodation and food services, compared to 5 per cent of UK workers.

However, it is also important to note that migrants make a large contribution to sectors of the economy that are of particular importance in the context of the current crisis. Notably, EU migrants are concentrated in the food manufacturing sector while non-EU migrants are concentrated in health and social care – two sectors that will be of vital importance for the public in the coming weeks. In total, around 850,000 migrants work in health and social care – around one in five of the total workforce – while migrants make up more than 40 per cent of workers in food manufacturing.

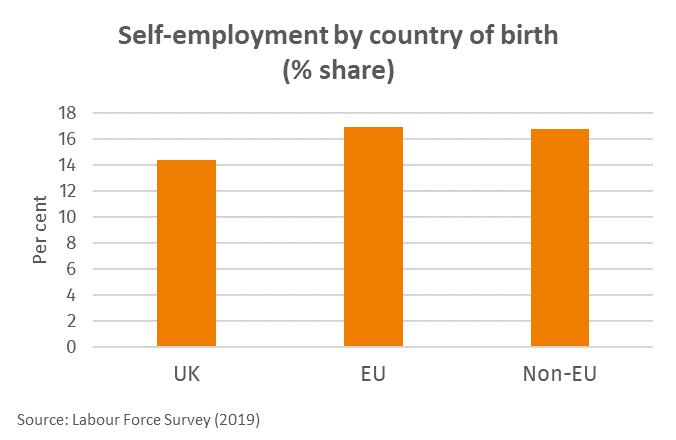

Migrant workers are more likely to be self-employed and less likely to be unionised

While the government has offered a generous wage package for workers on employer payrolls, there is currently far more limited support for the self-employed. Temporary workers are also more vulnerable, given their contracts might finish soon and they could struggle to find new work.

Our analysis finds that migrant workers are more likely to be self-employed than UK-born workers: 17 per cent of EU and non-EU workers are self-employed, compared to 14 per cent of UK workers. Around 6 per cent of EU employees and 7 per cent of non-EU employees are in temporary positions, compared to 5 per cent of UK-born employees. Moreover, migrants – particularly people born in the EU – are considerably less likely to be members of trade unions, making them more vulnerable to unscrupulous employer practices.

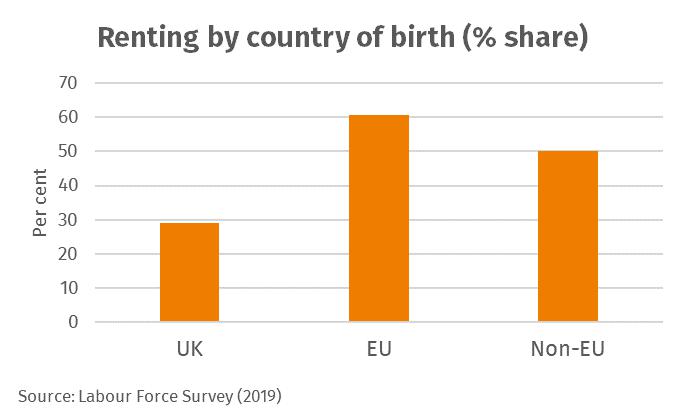

Migrants are less likely to own their own homes and are more likely to live in private rented accommodation

The impact of the coronavirus crisis is likely to vary considerably depending on housing tenure. Those with larger homes will find it easier to practise social distancing and self-isolation, while those who own their own homes outright are more financially secure. The government’s housing measures so far have focused on households with mortgages – the Chancellor offering a three-month mortgage holiday for those who cannot afford to pay due to the crisis – while the measures to protect renters from eviction have been critiqued as inadequate.

Our analysis suggests that migrants are significantly less likely to own their own homes and are much more likely to be renting – 54 per cent of migrants rent their property (61 per cent of EU migrants and 50 per cent of non-EU migrants), compared to 29 per cent of the UK born. They are also particularly likely to rent via private landlords. In addition, a relatively high share of migrants have accommodation tied to their employment: 4 per cent of EU born tenants (including those who pay no rent at all) and 5 per cent of non-EU born tenants have accommodation linked to their jobs, compared with 3 per cent of the UK born. This puts them at particular risk of eviction and homelessness if they lose their job as a result of the coronavirus crisis.

Finally, migrants are also more likely to be living in overcrowded housing (Migration Observatory 2019). Self-isolating and social distancing could therefore place particular practical and mental health pressures on migrant communities.

Responses

This short briefing has explored evidence suggesting that migrants – both the EU and non-EU born – are at particular risk of the economic fallout of coronavirus. Migrant workers are more likely to have jobs in affected sectors, more likely to be self-employed and so not eligible for the government’s job retention scheme, and more likely to live in private rented and overcrowded accommodation.

The risks for migrants are particularly important because many migrants already face significant barriers to accessing government support. Many non-EU migrants – for instance, those on spousal or student visas – are not entitled to government support because their visa conditions stipulate they can have ‘no recourse to public funds’ (NRPF). And while this restriction does not apply to EU citizens, some EU migrants (e.g. workers who have become unemployed) nevertheless have to undergo the Habitual Residence Test, including the ‘right to reside’ requirement, to access benefits such as Universal Credit. For people in this situation, the coronavirus crisis could trigger severe hardship and destitution without any social safety net. Moreover, the financial impact of losing income is likely to force many migrants to continue working, despite the risks to their own health and to the wider public.

Based on our analysis of the particular risks facing migrant workers and households, we propose the following urgent and temporary changes to support public health and avert the worst financial impacts of social distancing and self-isolation:

- All new measures designed to support UK workers should equally apply to EU and non-EU workers.

- The ‘NRPF’ conditions should be suspended so that all migrants living in the UK can access benefits and public services.

- The Habitual Residence Test should be suspended so that EU migrants do not need to prove their ‘right to reside’ in order to access benefits such as Universal Credit.

Without such measures, our analysis suggests that the financial and health consequences of the current crisis could be particularly severe for migrant workers and households, with knock-on effects for communities across the country. To protect public health and livelihoods, the government must therefore take this action as quickly as feasible.

Marley Morris is IPPR Associate Director for Immigration, Trade and EU Relations

Related items

Reclaiming social mobility for the opportunity mission

Every prime minister since Thatcher has set their sights on social mobility. They have repeated some version of the refrain that your background should not hold you back and hard work should be rewarded by movement up the social and…

Facing the future: Progressives in a changing world

Realising the reform dividend: A toolkit to transform the NHS

Building an NHS fit for the future is a life-or-death challenge.