Mind the G.P: Pay Inequality amongst General Practitioners

Article

Introduction

Equality is built into the DNA of the NHS. It is free at the point of need, for everyone, when we need it most. This means that the NHS should be held to the highest standards of social justice – whether in its provision of care to the people it serves, or in the way it treats its workforce.

One of the key frontiers of equality in recent years has been equal pay for men and women. Since 2017, when the statutory duty to report on gender pay gaps was introduced, it has rightly become a point of intense scrutiny. In early 2018, this led then health secretary Jeremy Hunt to announce an independent review into the gender pay gap (Independent, 2018). Yet, though there were some brief interim findings last year, the final report remains due. More generally, the NHS has flown under the gender pay radar. Indeed, it has been the subject of far less discussion than many other public bodies. Relatively little is subsequently known about health service pay inequality and its causes.

General practice provides a particularly interesting point to begin enquiries. Its provider model is unique in the health service. Since the NHS was formed in 1948, provision has been delivered by many thousands of small general practices. Broadly speaking, these practices operate as ‘partnerships’ – owned and run by general practitioners as private businesses that deliver NHS services. It’s thus unique in being an NHS workplace where pay is not mandated centrally, where HR is left to business owners and where on Doctor might hire another and pay them directly.

Historically, this model was used to allow ‘family doctors’ to provide tailored care to a population they lived in and knew well. However, in the 21st century, it is important to know how compatible this model is with equality and social justice – and whether a model that hasn’t radically changed in 70 years remains aligned to contemporary social priorities.

The pay gap in general practice is unjustifiably high

The size of GP practices means they do not systematically report on pay inequality. New IPPR analysis uses the latest workforce and earnings data to provide, in lieu of that, a comprehensive estimate of the general practice pay gap in England. This analysis shows that men working as GPs earn, on average, an estimated £110,000 per year. By contrast, a female GP earns, on average, an estimated £70,000 per year. Neither constitute poverty wages, but the gap between them is huge: 35 per cent. (NHS Digital, 2019a and 2019b)

To put that in context, it is more than twice the most recent ONS estimate of the average UK pay gap across the economy (16.2 per cent) (ONS, 2019 – using mean values) – indeed, it is the fifth largest out of all the professions the ONS analyse. It is the equivalent of women GPs earning nothing between the August bank holiday and Christmas. And even when controlling for part-time work, the gap is 17 per cent - again, significantly higher than the average in the wider economy.

No matter age or contract, men are paid more than women

Women face multiple inequalities at work. They might face more barriers to progression, less tailored support or unconscious bias. When it comes to pay, a particular problem is women being paid less than male counterparts in the exact same role.

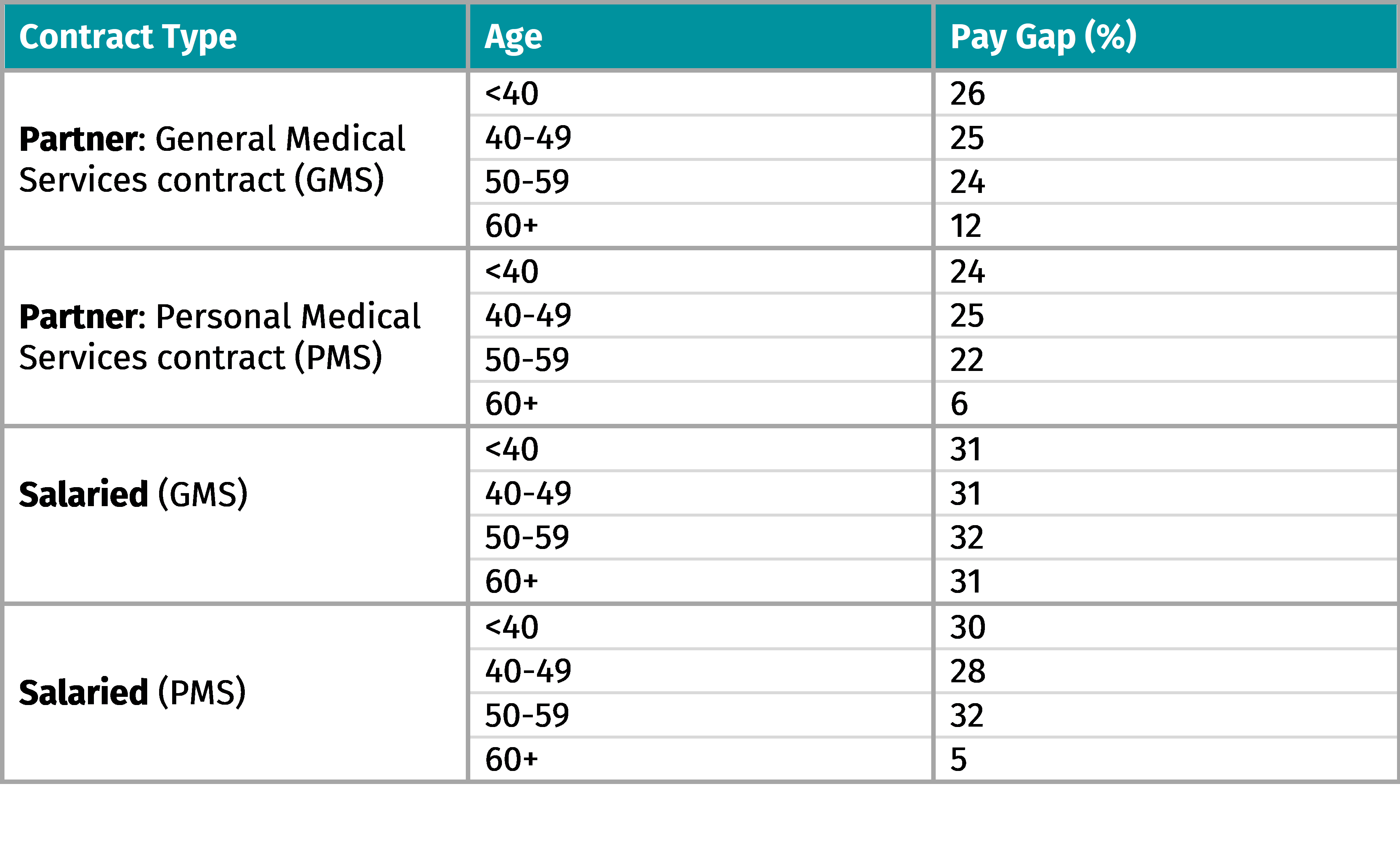

IPPR analysis shows this trend is very much prevalent in general practice. Indeed, there is no age or contract type where a man is not paid more than a woman counterpart. This is not the only driver of the pay gap – how many men and women fill each role is another key element – but it is indicative of a structural inequality.

Table 1:Women earn less on average than men of the same age and on the same type of contract

There are reasons for the pay gap unique to general practice

There are several factors that seem to underpin the substantial GP pay gap. Firstly, women are more likely to work part time than men. Our analysis shows that the average male GP works 0.88 FTE (full time equivalent) – the average woman 0.69 FTE. This might be because of an increased need for flexibility, perhaps to care for children or relatives – itself an indication of the unequal distribution of unpaid labour in society (NHS Digital, 2019b).

Women GPs are also younger, on average. Around 35 per cent of women in the GP workforce are under the age of 40, compared to just 22 per cent of men. In reality, the difference this makes in general practice is slighter than in other careers – GPs are highly skilled and pay progression not substantial, particularly in partnership roles where pay is on an equity basis. Nonetheless, there is a correlation (Ibid).

A third factor is more unique to general practice: the partnership model. Just under 50 per cent of women are partner GPs, compared to almost 80 per cent of men. Partners own the business and make profit. They make the strategic decisions, they hire other (salaried) doctors and ensure the business is efficient. For this, they are paid significantly more: around £110,000 to £60,000 in a salaried role. This can’t help but drive the overall pay gap.

Conclusion

The pay gap in general practice is, then, about both wider social inequalities, but also about some of the unique elements of the provider model used in general practice. It is not wholly surprising that a model, that has not radically changed since 1948, has not kept up with the evolution of social standards over the last 70 years.

It is time to review what more can be done to provide a fair deal for one of the country’s most cherished and hardworking professions.

Yet, equal pay in general practice is not just a question of fairness for staff. It is also critical to ensuring high quality care for all in the future. General practice is currently under huge strain – with staff numbers stagnating despite government commitments to recruit more doctors. This is likely to only get worse, with the population of England both growing and aging – meaning more and more complicated patients in primary care.

Providing fair working conditions will be critical to ensuring the right staffing in the future – particularly as woman now make up the majority of the workforce (as of 2014). If general practice accepts a pay gap higher than the wider economy and the wider NHS, it will struggle to provide an attractive workforce, particularly in competition with other medical specialties.

The onus is on a new government, who committed to providing 6,000 more GPs by 2025, to identify the causes of inequality and urgently mitigate them as they look to deliver on their manifesto pledges.

***

References:

Independent (2018) Jeremy Hunt Launches Independent Inquiry Into 15 percent Gender Pay Gap for NHS Doctors https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/jeremy-hunt-nhs-doctors-gender-pay-gap-inquiry-health-a8372701.html

NHS Digital (2019a) GP Earnings and Expenses Estimates https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/gp-earnings-and-expenses-estimates/2017-18

NHS Digital (2019b) General Practice Workforce https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/general-and-personal-medical-services/final-30-september-2019

Office for National Statistics (2019) Gender Pay Gap. Dataset. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2019/relateddata

Related items

The health mandate: The voters' verdict on government intervention

The nation’s health is now a top-tier political issue.

Reclaiming social mobility for the opportunity mission

Every prime minister since Thatcher has set their sights on social mobility. They have repeated some version of the refrain that your background should not hold you back and hard work should be rewarded by movement up the social and…

Realising the reform dividend: A toolkit to transform the NHS

Building an NHS fit for the future is a life-or-death challenge.