To support low-income households, it's time to reduce the cost of daily bus travel

Article

A new secretary of state for transport has inherited a bus network in need of a significant intervention to boost passenger numbers after decades of decline. The Department for Transport have recently announced a three-month cap of £2 on the cost a single adult fare. This is a welcome move, but it doesn’t go far enough to address the cost of bus use for regular users. Below, we outline national policies that would live up to the moment – supporting people with the rising costs of living and making England’s transport system fairer.

In response to the rising costs of living and the need to reduce energy demand, several countries have implemented schemes to promote public transport.

These range from Germany’s €9 a month ticket for unlimited regional travel (in place for three months during the summer), Austria’s new ‘Klimaticket’ which allows unlimited public transport use for the equivalent of €3 a day and New Zealand’s halving of public transport fares from April 2022 to January 2023. At a more local level, cities like Dunkirk in northern France have been running a fare-free bus service since 2018 and Tallinn, Estonia, made public transport fare free for residents back in 2013.

Meanwhile, the UK government have announced that rail fares rises will be below inflation in 2023 and are providing support to bus operators to cap single adult fares at £2 from January to March 2023. Although both announcements are welcome, it should be apparent that they are nowhere near the scale required to deliver a fairer, greener transport system.

We'll focus here on bus fares, but it is worth noting on rail fares that there have rightly been calls for a fare freeze and longer term reform of the way fares are set.

Context for reducing the cost of bus travel

The best long-term option for improving local transport, decarbonising the bus fleet and reducing the cost of bus travel is to provide local transport authorities (LTAs) with appropriate powers and funding. Recent analysis by the Campaign for Better Transport of Bus Service Improvement Plans (BSIPs) showed that around £10 billion would be needed to fund all BSIPs – but only £1.1 billion was allocated from the ‘transformational’ government funding set aside to deliver these, with just 40 per cent of the LTAs who applied receiving any funding at all. There is no shortage of ambition to improve bus travel, but national government has not provided the investment required to deliver on it.

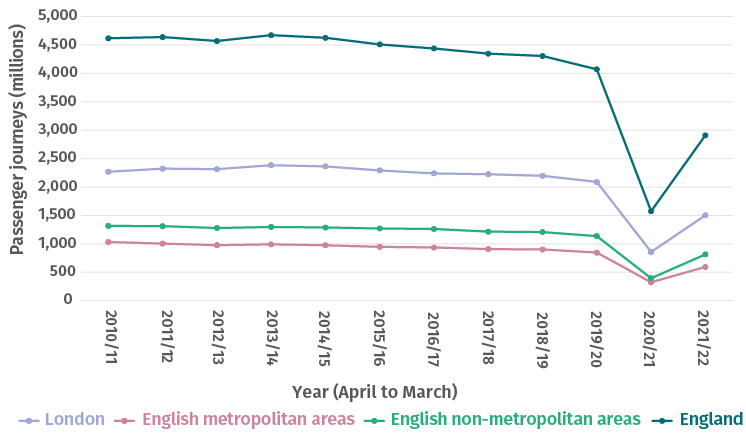

For households facing steep cost of living increases, support is needed to ensure that bus travel is affordable to all, and that people can access the things they need via local public transport. The bus network is also badly in need of new passengers with bus usage declining over the last decade and yet to return to pre-pandemic levels (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Passenger journeys on local bus services have fallen in England over the last decade, and have not yet recovered from the impact of the measures taken during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic

Passenger journeys on local bus services per year in England (millions)

Source: IPPR analysis of DfT (2022), Table BUS0106a

Fares vary across English regions, with a range of prices for singles and returns, as well as daily and weekly travel passes. In 2019, the average cost of a single fare was almost £2.50, and a day ticket was over £5.20. Authorities that have already reduced the cost of single adult fares have not all been able to invest in reducing the cost of day tickets (for example, Liverpool are reducing single fares from £2.30 to £2, but making no change to the £5 day ticket).

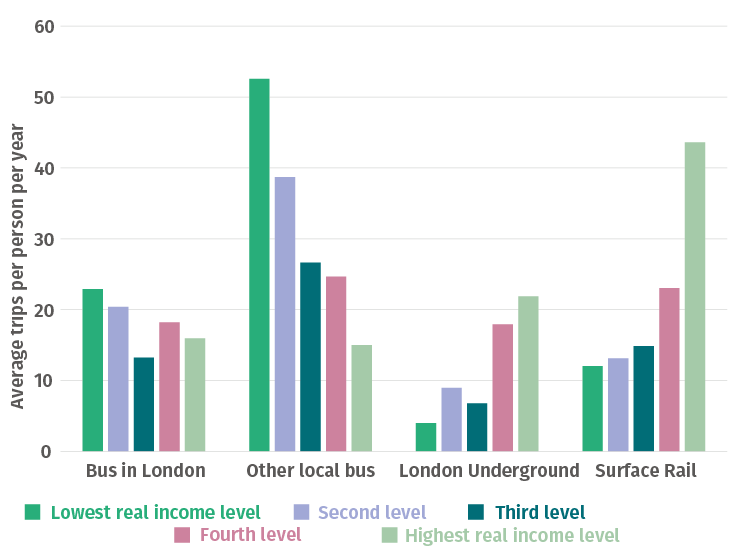

Rising bus fares have disproportionately impacted those on the lowest incomes, as they are the most likely to use these services (see figure 2). Since 2013, bus users have seen bus and coach fares rise faster than average wages, rail fares, and the cost of motoring. Deregulation and lack of appropriate, long-term funding for the bus network has failed those who have limited access to alternative transport options.

Figure 2: Low-income households use buses more than other public transport modes

Trips per person per year by main mode and real household income quintile (2019)

Source: IPPR analysis of DfT (2022), Table NTS0705

Fare reductions alone may not lead to reduced car usage. Improving bus services, investment in active travel and making the use of more polluting vehicles less attractive (such as clean air zones) are all required to decarbonise transport. Fare reductions will help deliver a fairer transport system and ensure that climate policies are perceived as fair to all income groups – not just those who can afford to purchase electric vehicles.

An England-wide approach to reducing bus fares for a year

IPPR’s Environmental Justice Commission recommended that local public transport should be made free at the point of use – with increased powers for LTAs to raise revenue to support this alongside national investment in decarbonising the bus fleet. IPPR Scotland’s report on fairly reducing car use in Scotland backed the Poverty Alliance’s calls for the extension of fare-free bus travel from young people to people on low incomes.

These policies should be the inspiration for a one year, England-wide (including London) emergency scheme to reduce the cost of bus fares. Alternatives to fare-free travel could include capping a single ticket at £1 or a day ticket at £1. After a year, a longer-term funding settlement to support lower fares should be agreed with LTAs. IPPR’s indicative costing for these interventions, their potential impact on the number of bus journeys and associated reduction in car use are shown in table 1.

Table 1: Indicative costs for interventions targeting a reduction in the cost of bus fares in England

Scheme | Description | Indicative cost (per annum, 2022/23 prices) | Estimated increase in bus journeys (bns per annum) | Estimated reduction in car trips and car kms travelled (bns per annum) |

Free bus travel for all | A national scheme to make all bus travel free across England for one year. | Up to £2.3bn | Up to 1.05 | Trips – 0.25 Car kms – 2.76 |

| Free buses for those who need them most | A new concessionary scheme to make bus travel free for young people (under 25) across England for one year. | Up to £0.5bn | Up to 0.33 | Trips – 0.06 Car kms – 0.66 |

| A new concessionary scheme to make bus travel free for everyone on Universal Credit across England for one year. | Up to £0.1bn | Up to 0.05 | Trips – 0.01 Car kms – 0.11 | |

| A concessionary scheme that provided free bus travel in England for a year for everyone on Universal Credit and young people (under 25). | Up to £0.5bn | Up to 0.36 | Trips – 0.07 Car kms – 0.74 | |

| Reduced bus fares for all | Wherever you are in England, bus travel never costs more than £1 a day, for a year. | Up to £1.7bn | Up to 0.84 | Trips – 0.2 Car kms – 2.21 |

| Wherever you are in England, bus travel never costs more than £1.50 a day, for a year. | Up to £1.4bn | Up to 0.74 | Trips – 0.18 Car kms – 1.94 | |

| Wherever you are in England, a single bus fare never costs more than £1, for a year. | Up to £0.9bn | Up to 0.5 | Trips – 0.12 Car kms – 1.32 | |

| Wherever you are in England, a single bus fare never costs more than £1.65, for a year. | Up to £0.3bn | Up to 0.14 | Trips – 0.03 Car kms – 0.38 |

Source: Authors’ analysis

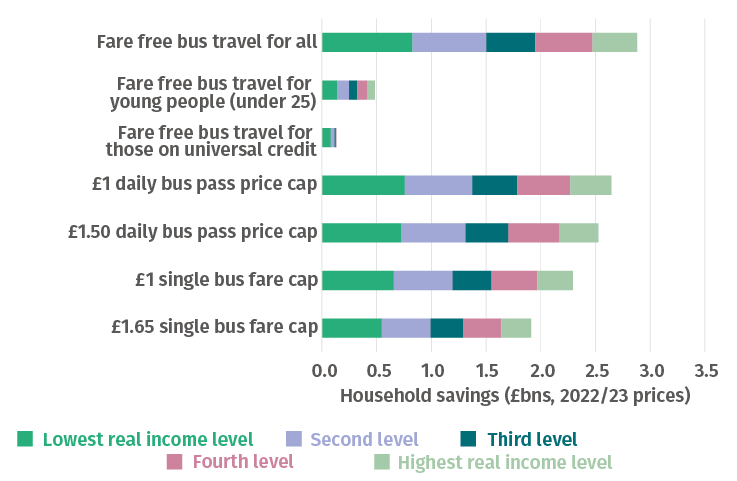

If the higher-end estimate of passenger number increases was achieved through these policies (see table 1), a £1 daily price cap could see up to a £0.8 billion combined household saving for those in the lowest income quintile, with fare-free travel also delivering up to £0.8 billion of savings (see figure 3).

Figure 3: The lowest income households have the highest savings from policies to reduce bus fares in England

Household savings by real household income quintile (£bn, 2022/23 prices)

Source: Authors’ analysis

Recommendations

Action to reduce the cost of bus travel should go further than the £2 flat fare for single tickets for three months that has been announced by government.

Under new leadership, DfT should look again at their plans for providing support to the lowest income households to reduce their transport costs and to make public transport more attractive.

At least an annual scheme is required, and the price cap needs to support more affordable return trips and daily travel. To best target resources, it may be appropriate to offer a significant extension in concessionary schemes alongside a new flat fare for day trips – this would ensure that the benefits from this intervention were targeted at those who need them most.

How might such a scheme be funded? The government chose to make over £40 billion worth of tax cuts in its most recent mini budget, just a small proportion of that spending could be better allocated to reduce bus fares. Alternatively, the government could review the £27 billon budget allocated to Roads Investment Strategy 2, which will also exacerbate the climate and nature crises, though it should be noted this is investment spend rather than day to day spending.

For a summary of the methodology and assumptions made within this analysis, download our technical annex below.

Downloads List

Related items

Planes, trains and automobiles: How green transport can drive manufacturing growth in the UK

Transport is essential to our lives. Unfortunately, it is currently also the largest source of UK domestic carbon emissions.

Regional economies: The role of industrial strategy as a pathway to greener growth

Regions like the North should have a key role to play in the development of a green industrial strategy.

Achieving the 2030 child poverty target: The distance left to travel

On 27 March, the Scottish government will announce whether Scotland’s 2023 child poverty target – no more than 18 per cent of children in poverty – was achieved.